Evaluation of the Food Standards Pilot in Wales: Annex 1 The proposed food standards delivery model

The proposed model introduces a new food standards intervention risk rating scheme that seeks to provide an accurate assessment of the potential risk posed by a food business.

The following description comes from the FSA presentation documentation and the England and Northern Ireland Food Standards Pilot Evaluation final report.

The proposed model introduces a new food standards intervention risk rating scheme that seeks to provide an accurate assessment of the potential risk posed by a food business. It incorporates three elements (Figure A1.1):

- A single, modernised risk assessment scheme that aims to unify the way that LAs risk assess establishments (a new risk scheme).

- Using the risk assessment scheme to identify the appropriate frequency for official control activity based on levels of inherent risk and compliance (decision matrix).

- Greater integration of intelligence as a driver of local authority regulatory activity and to inform our national understanding of food standards risk.

Figure A1.1 The three elements of the proposed new food standards delivery model

Diagram depicting the three elements of the Food Standards Delivery Model: the New risk rating scheme, the Decision Matrix and Intelligence.

A1.1 Proposed risk assessment scheme

The proposed risk scheme (Table A1.2) was designed to address known issues with the existing risk schemes, and to modernise the regulatory approach so that it better reflects new food business models and provides a more dynamic and accurate assessment of food business risk.

For example, the existing Food Law Code of Practice risk assessment scheme was felt to give too much emphasis to the inherent risk of a food business, failing to adequately recognise the business’s level of compliance. This often resulted in highly compliant businesses being inspected by LAs at a higher frequency than was deemed necessary under the current framework.

The proposed model’s intervention risk rating scheme takes into account the ‘inherent risk’ associated with the business and the level of current and, when appropriate, sustained compliance demonstrated by the business following a ‘compliance assessment’.

The inherent risk profile gives an indication of the risk associated with a particular food establishment and the compliance assessment evaluates the food business’s performance. The Inherent Risk Profile comprises of 5 separate factors, while the Compliance Assessment comprises 4.

| Risk element | Risk factor |

|---|---|

| Inherent Risk Profile | Scale of supply and distribution |

| Inherent Risk Profile | Ease of compliance |

| Inherent Risk Profile | Complexity of supply chain |

| Inherent Risk Profile | Responsibility for information |

| Inherent Risk Profile | Potential for product harm |

| Compliance Assessment | Management systems and procedures |

| Compliance Assessment | Allergen information |

| Compliance Assessment | Current compliance level |

| Compliance Assessment | Confidence in Management (CIM) |

Inherent Risk

- Scale of supply - This factor considers the number of consumers likely to be at risk if the establishment fails to comply with food standards legislation. The greater the number of customers the greater the potential impact of any non-compliance.

- Ease of compliance - This factor considers the volume and complexity of food standards law that applies to the establishment, and with which it has a responsibility to ensure compliance.

- Complexity of supply chain - The complexity of a food establishment’s supply chain increases risk as there is greater potential for problems with the foods and products they use, which in turn enter the supply chain. Recognition as well to potential consequences if and when carrying out a potential product recall.

- Responsible for information - The risk increases where an establishment is responsible for providing information about its products to its customers. There is potential for human error in compiling or communicating the product information which must be provided to consumers, as well as the opportunity for misleading claims or food labelling breaches to be included.

- Potential for product harm - This risk factor considers the extent to which consumers may suffer harm, whether physical or financial, and to which legitimate establishments may be disadvantaged, by the supply of food which is not compliant. For example, foods aimed at particular groups (medical foods, free-from) and high value foods increasing the incentive for substitution/adulteration.

Compliance Assessment

- Management systems/procedures – This factor considers internal/external quality management systems & whether assurances are in place, how these are implemented and verified. Proportionate to the size, scale and nature of the establishments.

- Allergen Information – This factor considers how well the business controls the aspects of allergen management and provision of allergen information applicable to them.

- Compliance level – This factor considers the current level of compliance with food law as witnessed during the intervention.

- Confidence in Management – This factor considers the likelihood of whether a business will be compliant or not given their history of compliance, attitude to compliance, management systems in place (including allergens) etc.

Each of those nine factors is given a score of 1 to 5, with 1 being poor and 5 being good. (9 factors scored in total). For both categories, the scores attributed to each of their factors is averaged to provide the respective inherent risk and compliance assessment scores.

Definitions of “broadly compliant”

Due to the change in the scoring approach the proposed model uses a different definition of “broadly compliant” and “non-broadly compliant”. Whether a premises has a status of broadly compliant or non-broadly compliant has no impact on the frequency of interventions or the burden placed on LAs. These terms are used by the FSA and LAs to get a high-level understanding of how FBOs are operating and how compliance is changing over time. The two different definitions of “broadly compliant” are set out below:

- The current definition under the Food Law Code of Practice (Wales): an establishment that has a score of not more than ten points under both the Level of (Current) Compliance and the Confidence in Management/Control Systems.

- The definition under the proposed Food Standards Delivery Model: an establishment receives an overall compliance risk assessment score of 3, 4 or 5.

“Non-Broadly Compliant” would be any establishment that does not satisfy the above requirements. So, under the Food Law Code of Practice, if an establishment had a score of more than 10 for either the Level of Current Compliance or the Confidence in Management they would be regarded as non-broadly compliant. For the proposed Food Standards Delivery Model, an establishment would be "non-broadly compliant" if it received an overall compliance risk assessment score of 1 or 2.

The assurance rule

A principle of the proposed model establishes a rule where, if one of the risk factors of the compliance assessment has been identified as a significant non-compliance, and so given a low score of 1, the overall compliance assessment score will be 1 regardless of the performance of the other risk factors. This rule provides assurance within the proposed model that significant non-compliance will attract more frequent official controls.

The two scores are then used in conjunction with the Decision Matrix to determine the frequency of interventions for that establishment.

A1.2 Proposed decision matrix

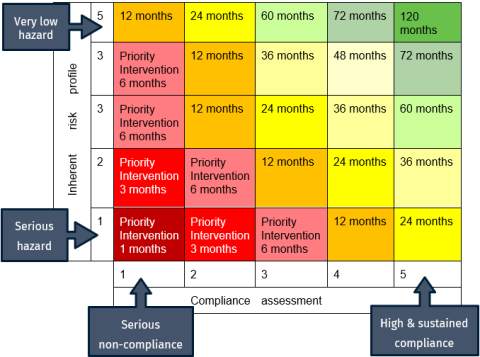

The proposed decision matrix (see Figure A1.2 below) follows a more graduated approach than the current model so that those businesses posing the highest risk are subject to an official control at a higher frequency than those posing a lower risk, thus enabling LAs to focus their resources on those establishments posing a greater risk to public health and consumer protection.

Figure A1.2 The proposed decision matrix

Table mapping risk and compliance levels. Arrow along the inherent risk axis points to a scenario of an inherent risk score of 5 and a compliance assessment score of 1 which is an example of a Very low hazard. Arrow along the inherent risk axis points to a scenario of an inherent risk score of 1 and a compliance assessment score of 1 which is an example of a Serious hazard. Arrow along the compliance assessment axis points to a scenario of an inherent risk score of 1 and a compliance assessment score of 1 which is an example of Serious non-compliance. Arrow along the compliance assessment axis pointing to a scenario of an inherent risk score of 1 and a compliance assessment score of 5 which is an example of High and Sustained compliance.

Those food businesses posing the most severe risk will be subject to a more intensive frequency of official controls and those presenting the very lowest level of risk subject to less frequent controls. This will enable LAs to focus their resources on establishments requiring prompt action to safeguard public health (allergens) or consumer protection. Those businesses posing the greatest risk are deemed to require a “Priority Intervention”, as seen in the bottom left-hand area of the matrix.

Priority interventions are currently Category A businesses with 12-month intervention frequencies, however under the new model priority interventions cover all businesses with an intervention frequency of 6 months or less.

When undertaking a priority intervention, officers should focus on those areas of concern and rescore the establishment on that basis, therefore a partial inspection/intervention may be sufficient, with the intention of working towards a more compliant establishment and a less intensive intervention frequency.

If following an inspection, an establishment’s intervention frequency is determined to be a priority intervention, corrective action should be taken to address the non-compliances. This could involve a revisit (focussed inspection) the following day or week. This will be on a case-by-case basis and dependent on the non-compliances found and should be in line with the hierarchy of enforcement, and in accordance with the Code.

Within that intervention frequency it is expected that the establishment would be re-risk rated to reflect any improvements made. Ideally the intervention frequency will have improved (i.e. moved out of the priority intervention frequency category). So, under the proposed new model, food standards officers can re-risk rate a premises following a focussed inspection – what the FSA currently regard as a re-visit is actually a focused inspection/focused audit.

A1.3 Remote interventions

The purpose of Remote Interventions (RI) is to allow LAs to remotely assess levels of food law compliance and verify activities at food establishments as appropriate and as determined by the LA in line with the Official Controls Regulation. Rather than a physical inspection, the LA can assess an establishment’s level of compliance without visiting it. Establishments in this category will typically have high levels of compliance and lower inherent risks.

RIs will involve the use of a variety of approaches and techniques by LAs to monitor and verify the food establishment’s activity and compliance with food law. It is for LAs to determine when an RI is an appropriate official control.

The principles of an RI are as follows:

- Confirm the business is still trading, under the same Food Business Operator.

- Focus on the aspects of the establishment that can be assessed remotely to determine their ongoing levels of food law compliance.

- Review the inherent risks of the establishment so the inherent risk scores can be amended if required.

Use of RIs does not mean LAs should avoid having direct contact with food establishments. The LA may decide to engage with establishments through various channels such as phone, email or letter, to obtain the evidence they need to complete the RI.

Under an RI, the establishment can be asked to provide documentation that will allow the LA to assess their levels of compliance. An RI could involve one or more of the following:

- A review of products on the food establishment’s website

- A review of product labelling

- A check of traceability records

- Sampling to verify the compliance of products

- Product specification checks

- Steps taken to ensure the accuracy of information and requirements of food law

- The provision of food management system information to support due diligence checks.

A1.4 Intelligence use

The proposed new model aims to formalise the use of intelligence. Chapter 4.3.2 of the current Code states that when new information becomes available that might suggest the nature of a food business’s activities has changed, or the level of compliance has deteriorated, LAs can reconsider the appropriateness of the current intervention rating, decide whether it is appropriate to undertake further activities (inspection, partial inspection, audit, investigate further), revise the intervention rating and then record the adjustment and the justification for doing so.

As a result, the proposed new model seeks to reaffirm to LAs that intelligence can initiate a re-assessment of the risk posed by a business and a review of the date of the next official control.

A1.5 New businesses: inherent risk desktop assessment

The desktop assessment of the inherent risk should be used to prioritise the initial inspections of new food businesses. For new businesses, a desktop assessment of the establishment’s Inherent Risk should be carried out within 28 days of the business registering, or from when the LA becomes aware the business is trading – whichever is the sooner.

It is envisaged that information provided through the Register a Food Business (RAFB) process should provide sufficient detail to enable the inherent risk profile to be assessed – looking at aspects such as the type of business (e.g. manufacturer, retailer, caterer), their position in the supply chain (e.g. wholesalers, selling online) and their trade activities (importing or exporting).

LAs should also use any other relevant information to help inform the assessment. This could be obtained by a search of the company’s online profile, telephone conversations, exchange of emails or questionnaires.

For businesses deemed to have a high inherent risk, so given a score of 1 or 2, their initial inspection should be undertaken within 1 month of the business opening or, if it had commenced trading prior to registering, within a month of the desktop assessment being carried out – whichever is the sooner. For businesses deemed to pose a moderate inherent risk, so given a score of 3, they should receive their initial inspection within 2 months. Those assessed as being low risk, so given an inherent risk score of 4 or 5, should be inspected within 3 months. At the initial inspection, a more accurate inherent risk assessment can be obtained alongside a compliance assessment to determine the frequency of future interventions.

Initial inspections should be prioritised so that those with a lower inherent risk do not cause undue delays to the delivery of official controls at higher risk/non-compliant businesses. It is acknowledged that some businesses are not permitted to trade until they have received an inspection, and these may have a low inherent risk – in such instances it would be acceptable to prioritise such businesses over relatively more risky businesses to prevent undue burdens/barriers to trade.