Evaluation of the Food Standards Pilot in Wales

This report presents the findings from the evaluation of the pilot project that the Food Standards Agency (FSA) has completed to test a proposed food standards delivery model in Wales.

This report presents the findings from the evaluation of the pilot project that the Food Standards Agency (FSA) has completed to test a proposed food standards delivery model in Wales. The aim of the pilot project in Wales was to test the food standards delivery model recently introduced in England and Northern Ireland to determine its suitability for Wales and identify any unintended consequences.

The model was introduced in England and Northern Ireland following a 15-month pilot (January 2021 to March 2022) and a subsequent consultation period across the two nations. This pilot in Wales builds on the findings from the England and Northern Ireland pilot as well as feedback received during the consultation process.

The evaluation methodology focused on capturing local authorities (LAs) experiences through pre- and post-pilot interviews with the participating LAs, interviews with FSA officials, and quantitative data submitted by the participating LAs and collected by the FSA’s analytical unit. Data was then analysed and triangulated to integrate the qualitative and quantitative findings against the evaluation research questions.

The pilot of the proposed food standards delivery model in Wales has been successful in demonstrating that the proposed model works in the Welsh context, and LAs were supportive of the new proposed allergen risk factor and the new intervention frequencies. The findings show that the proposed food standards delivery model and its core elements, a new risk assessment scheme and associated decision matrix, worked well. Key benefits included greater flexibility in the model, the ability to re-score premises following what is currently referred to as a re-visit and the ability to give a standalone score for allergen procedures. LAs highlighted the proposed risk scheme was straightforward to use and, by the end of the pilot, they had embedded the new way of working into their work practices. The proposed decision matrix, which indicates intervention frequency, was also seen as beneficial. However, LAs did identify areas where clarity in the guidance could be improved to further promote consistency in scoring, e.g. the thresholds between allergen scores.

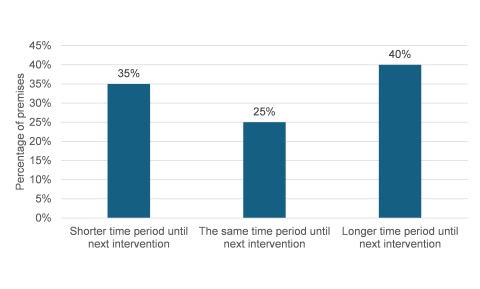

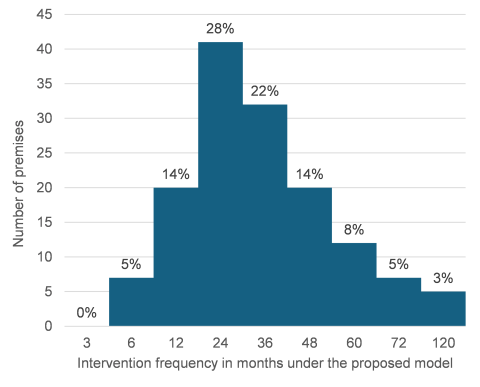

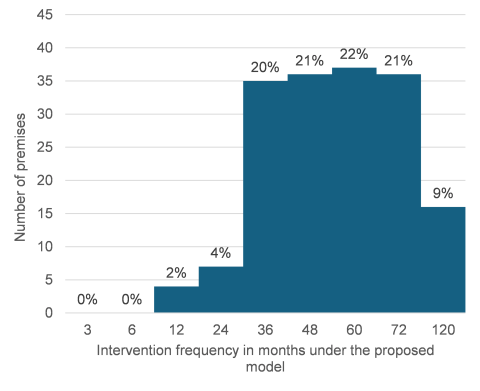

The process for implementing the pilot was successful. LAs reported that they received all the training and support prior to and during the pilot period that they required. LAs reported no challenges to implementing the pilot and that after a period of adjustment the proposed model was easy to use. The FSA also reported that the pilot had been a positive experience and they had not identified any unintended consequences. LAs reported no impact on resourcing during the pilot period but did raise concerns around how they would undertake annual service planning due to the proposed new shorter intervention frequencies. The quantitative data showed that while the number of premises whose intervention frequency increased (35%) was similar to those whose intervention frequency decreased (40%), the overall number interventions due increased by 14%. There may have been some more conservative scoring during the pilot as staff adapted to the proposed food standards delivery model thus increasing frequency of inspection for some premises.

Ahead of the roll-out of the proposed model in England and Northern Ireland the FSA have made reflections on the Wales evaluation findings and other feedback relating to the Welsh pilot. The FSA are considering additions to the guidance to increase clarity based on recommendations given in this report. The FSA stated that any additions would require a balance between providing prescriptive guidance and allowing flexibility for officers conducting food standards official controls to use their knowledge and experience to risk rate a business.

Introduction

This report presents the findings from the evaluation of the proposed food standards delivery model in Wales. This pilot evaluation builds on the findings from the England and Northern Ireland pilot evaluation.

The FSA piloted a proposed new food standards delivery model between January 2021 and March 2022 in England and Northern Ireland.

The evaluation in England and Northern Ireland found that the new elements introduced by the proposed food standards delivery model worked well. The new risk scheme better identified high-risk food businesses and offered benefits to Local Authorities (LA) such as greater flexibility in how to use the model, the ability to re-score premises and the ability to use intelligence to select the most appropriate intervention. LAs highlighted that the new risk scheme was straightforward to use, and by the end of the pilot, they had already embedded the new way of working into their work practices.

LAs identified some challenges during the pilot with the proposed model. Most were resolved within the pilot and the remaining ones (use of intelligence, use of targeted remote interventions (TRIs), and the identification of non-compliances linked to allergens), were addressed by adapting the proposed model to mitigate them. This adapted model was then subject to a formal consultation and amended further, taking formal responses into account. It was subsequently introduced in Northern Ireland (May 2023) and England (June 2023).

As LAs in Wales were unable to pilot the proposed model at the same time as England and Northern Ireland, the FSA piloted the food standards delivery model between September 2023 and February 2024 in Wales. This pilot built on the lessons learned from the previous pilot and the implementation of the model in England and Northern Ireland.

The evaluation of this pilot builds on the previous report and aims to answer the following questions:

- How did the proposed model perform compared to the current framework? What worked well and less well?

- What has been the experience of each of the stakeholders with respect to specific elements of the proposed model and the proposed model changes as a whole?

- What has been the effect on resources for each of the stakeholders because of the proposed model?

- What has been the overall effect of the proposed model? Did it deliver its objectives? Were there unintended consequences?

- What lessons were learnt from the pilot of the proposed model?

Methodology

The evaluation included a data collection and a data analysis phase, with two rounds of interviews with each of the four LAs that participated in the pilot, consisting of two pilot LAs and two control LAs. The study also included interviews with FSA staff, and a series of meetings with the FSA throughout the project. In addition, the FSA’s Analytics Unit gathered quantitative data throughout the pilot that has been integrated into the findings of this study.

Summary of findings

Findings have been structured around the research questions listed above.

How did the proposed model perform compared to the current framework? What worked well and less well?

Overall, the proposed model was fit for purpose and was generally easy to understand and use. Both pilot LAs perceived that the proposed model was an improvement in comparison to the current model. The proposed model provided a more balanced assessment of the food businesses, taking account of both the level of inherent risk and the level of compliance displayed. If the level of compliance is of sufficient concern, the proposed model determines that the next intervention to a business should be a priority intervention. This enables LAs to target their resources towards such visits with the aim of improving compliance. This is more in line with how the two pilot LAs feel interventions and the food standards service should be operating and was motivational for the teams.

The proposed risk scheme was seen as beneficial and the addition of the standalone allergen score was particularly valuable in assisting LAs to give allergens proportional focus within interventions and target resource where the risks are highest.

The proposed decision matrix, which indicates the intervention frequency for businesses, was also seen as beneficial.

LAs had overall positive reflections on the new model. LAs also identified lack of clarity with some terminology which made consistent implementation of the proposed risk scheme challenging at the beginning. These areas were:

- Guidance on the allergen scoring criteria and the thresholds between scores.

- Expanding on the risks of online distribution within the code and guidance.

- Definitions and interpretation of key terminology and phrasing.

What has been the experience of each of the stakeholders with respect to specific elements of the proposed model and the proposed model changes as a whole?

The experience of each stakeholder (LAs and the FSA) was overall very positive.

- LAs decided to join the pilot because they wanted to understand and influence the proposed model with the FSA, and to be able to adapt early to it. Their experience during the pilot met these expectations.

LAs reported that they received all the training and support prior to and during the pilot period that they required. They found the food business “risk assessment” scoring scenario exercise and discussion to be particularly beneficial for increasing understanding and highlighting areas of interpretation.

- There were few challenges reported regarding implementation of the proposed model.

- One LA highlighted concerns around the database mapping conducted to convert the risk score of the premises on their databases to the new risk assessment scheme of the proposed model.

- The proposed model had no impact on use or sharing of intelligence, sampling activities or use of remote inspections (these were aspects of the England and Northern Ireland pilot but were not a focus under the Wales pilot).

- LAs reported no unintended consequences from the pilot or the proposed model.

- The FSA reported that the proposed food standards model had run as expected and overall, the pilot had been a positive experience. They noted the request for further guidance and clarification on certain areas.

What has been the effect on resources for each of the stakeholders because of the proposed model?

LAs discussed resourcing in terms of:

- The pilot period: it was reported that there was no change in resourcing caused by the pilot itself or the proposed model during the pilot period. One of the two pilot LAs made a resourcing change during the pilot period, this was to support efforts to reduce the backlog of interventions and was not due to the proposed model.

- A potential wider roll out: concerns were raised around how to effectively plan and justify resourcing within annual service plans under the proposed model, particularly in light of external financial pressures on LAs.

It was mentioned that the proposed model would not address the shortage in resources and the backlog in inspections.

What has been the overall effect of the proposed model? Did it deliver its objectives? Were there unintended consequences?

The proposed model achieved its objectives of effectiveness, efficiency and impact:

- Effectiveness: The compliance scoring aspect of the proposed new risk assessment helped LAs target interventions and resource towards businesses that posed the most risk.

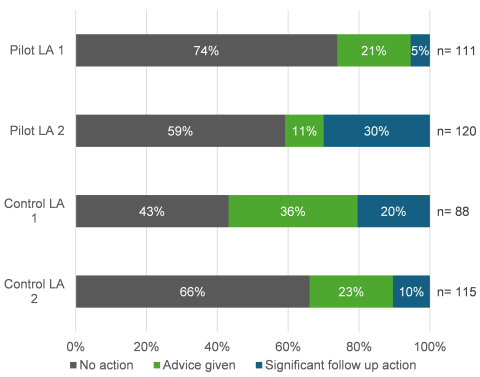

- Effectiveness: Quantitative data showed that pilot LAs identified significantly more allergen related issues than the control LAs, showing the value of the proposed standalone allergen information risk factor.

- Efficiency: LAs feel that the model does ensure that the resources available are used most efficiently to target the highest risk food businesses and enables better prioritisation of revisits to ensure rectification of non-compliances.

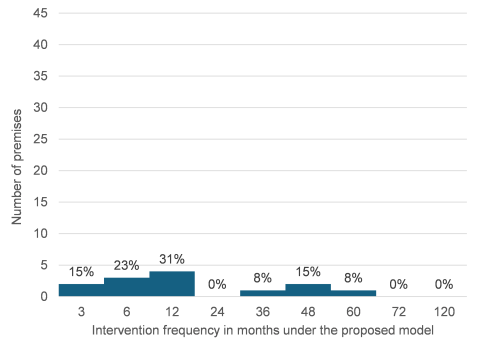

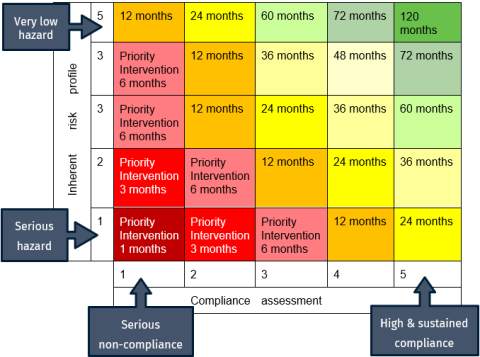

- Impact: The new shorter (1, 3 and 6 months) and longer (72 and 120 months) frequencies within the proposed risk matrix were identified for a range of food business types during the pilot. Therefore, the risk matrix is allocating intervention frequencies which are better aligned with compliance scores than previously (the inherent risk score appears to have a stronger influence on intervention frequencies under the current delivery model), meaning that intervention frequencies align better with the risks faced. Overall, the number of interventions due increased by 14%.

- Impact: The pilot and proposed model had very little effect on relationships between LAs and the FSA and no effect on relationships between LAs and businesses.

The evaluation team did not identify any unintended consequences of the pilot or proposed model.

What lessons were learnt from the proposed model?

The lessons learnt were structured in three areas, as shown in the table below:

| Area of the proposed model/pilot | Lessons learnt |

|---|---|

Implementation of the pilot (found in report section 3.1) |

The support provided by the FSA throughout the pilot was well received and crucial to the success of the pilot. To the extent possible, continue to consider timing of pilots to avoid busy period such as the end of financial year |

| The proposed new model (found in report sections 2.2, 2.3, 2.4 and 2.5) |

The proposed model was fit for purpose and was an improvement in comparison to the current model as it allocated risk ratings to establishments in a more balanced way than before. However, the accompanying guidance to implement the proposed model could be improved. There were few challenges reported in implementing the proposed model. The FSA reported that the proposed food standards delivery model had run as expected with no unintended consequences identified and overall, the pilot had been a very positive experience. |

| National roll-out (found in report section 3.2) |

Guidance and clarity around terminology used should be provided prior to a roll-out. An improvement in the definitions and descriptors would help with consistency in interpretation. There should be a continued forum (possibly external to the FSA) for sharing of experiences between LAs to encourage discussion around consistency and interpretation. Specific guidance should be provided to joint-service LAs to help maintain smooth working practices between the Food Hygiene and Food Standards services. This guidance should cover how to compare the Food Hygiene and Food Standards intervention frequency reports. Clarity needs to be increased around the allergen scoring criteria, by improving the descriptors in the risk assessment. Pilot LAs noted that this particularly relates to scoring of businesses with ‘no allergen risk’ due to the specific products they produce or supply as well as further clarity on the thresholds between each of the allergen risk scores. Support should be provided to LAs during the process of mapping databases from the current model to the proposed new model to reduce the risk of high-risk businesses being reclassified as non-priority due to issues with data entry. (This is already being implemented in England and Northern Ireland). |

This report presents the findings from the evaluation of the pilot of the proposed food standards delivery model in Wales. The pilot and the evaluation build on the findings from the England and Northern Ireland pilot evaluation.

The FSA piloted a proposed food standards delivery model between January 2021 and March 2022 in England and Northern Ireland. The proposed model was then subject to a formal consultation and amended further, taking formal responses into account, and has now been introduced in England and Northern Ireland.

LAs in Wales were unable to pilot the proposed model at the same time as England and Northern Ireland. Building on the previous pilot and implementation of the model in England and Northern Ireland, the FSA piloted the model introduced in England and Northern Ireland as a proposed new food standards delivery model to use in Wales between September 2023 and February 2024. The pilot tested a proposed new model for the delivery of food standards official controls. This introduced a modernised risk assessment approach that aims to support LAs target their resources more effectively; provide more flexibility to LAs; and help LAs meet their statutory obligations.

This is the final report of the evaluation of the proposed food standards delivery model in Wales.

The report is organised as follows:

- The rest of this section (section 1) introduces the background context for this pilot project and discusses the proposed food standards delivery model in Wales. It concludes by summarising the methodology followed by the evaluation study.

- Section 2 summarises the findings of the evaluation, organised by research question.

- Section 3 includes a series of considerations and lessons learned.

- Section 4 closes the report with the conclusions.

1.1 Background

This section introduces the background context for this pilot project. It discusses the findings from the England and Northern Ireland pilot evaluation study, describes the proposed food standards delivery model, introduces the Wales pilot project and provides background information on the local authorities in Wales.

1.1.1 Summary of findings of the food standards delivery model pilot in England and Northern Ireland

Between January 2021 and March 2022, the FSA tested a proposed food standards delivery model with eleven LAs in England and Northern Ireland (the ‘initial pilot’). The proposed food standards delivery model aimed to support LAs to target resources more effectively; provide better assurance and more flexibility to LAs; and to help LAs meet their statutory obligations. The proposed model introduced a modernised risk assessment approach, including a new risk assessment scheme, a decision matrix and the development of an intelligence-led approach to LA regulatory activity.

The evaluation of the initial pilot found that the new elements introduced by the proposed food standards delivery model worked well. The new risk scheme better identified high-risk food businesses and offered benefits to LAs such as greater flexibility in how to use the model, the ability to re-score premises and the ability to use intelligence to select the most appropriate intervention. Local Authorities (LAs) highlighted that the new risk scheme was straightforward to use, and, by the end of the pilot, they had already embedded the new way of working into their work practices.

LAs identified some challenges with the model. Most were resolved within the pilot. Other challenges like the use of intelligence, the use of targeted remote interventions (TRIs) or the identification of non-compliances linked to allergens, were addressed by adapting the proposed model to mitigate them.

This adapted proposed model was then subject to a formal consultation and amended further, taking formal responses into account, and has now been introduced in England and Northern Ireland.

1.1.2 The proposed food standards delivery model in Wales

The Food Law Code of Practice establishes a framework for the delivery of official food controls by LAs. It determines the appropriate intervention frequency for food businesses based on the associated risk profiles for different establishments and businesses. Each country in the UK has their own Food Law Code of Practice, and while those issued in Wales, England and Northern Ireland are generally similar, there are some country-specific differences. LAs in Wales must have regard to the Food Law Code of Practice (Wales) (hereafter, ‘the Code’) while fulfilling their duties in relation to food (both food hygiene and food standards).

For food standards, the existing intervention rating scheme groups food establishments into Category A (high risk, requires an intervention every 12 months), Category B (medium risk, requires an intervention every 24 months), and category C (low risk, should be subject to an intervention at least once every 60 months). This allows LAs to prioritise their interventions. LAs will visit all new premises to determine compliance with applicable food law and allocate a risk rating. Interventions by LAs can take the form of an inspection, partial inspection or audit. Under this rating scheme, some establishments, due to the nature of their activities, are identified as Category A (high risk) regardless of their level of compliance.

Additionally, the FSA and LAs can monitor the change in compliance from businesses over time using a metric of ‘non-broadly compliant’ and ‘broadly compliant’ businesses. These metrics are used by the FSA and LAs to get a high-level understanding of how FBOs are operating. The current definition of “broadly compliant” is set out below:

- Definition under the Code: an establishment that has a score of not more than ten points under both the Level of (Current) Compliance and the Confidence in Management/Control Systems.

“Non-Broadly Compliant” would be any establishment that does not satisfy the above requirements. So, under the Code, if an establishment had a score of more than 10 for either the Level of Current Compliance or the Confidence in Management they would be regarded as non-broadly compliant.

A series of reports (Research on the modernisation of the risk intervention rating systems for UK food establishments, Food Standards Delivery Review, and Ensuring food safety and standards) highlighted the need to change the current food standards delivery model under the Code. The reports identified several challenges with the current model, which, combined with a decline in LA resources and a rapid change and growth in the types of food establishments, showed that the current food standards delivery model is no longer fit for purpose.

The challenges highlighted by the reports were:

- LAs are taking inconsistent approaches to regulating food standards, as the current risk model doesn’t always accurately reflect the overall level of food business risk.

- The current model follows an establishment risk-based approach, which is perceived as not the most effective in identifying non-compliances.

- The current model does not support LAs in targeting their resources towards the areas of greatest risk.

The FSA Board approved a root and branch review of the food standards delivery in December 2018. Following this decision, the FSA designed the proposed new food standards delivery model in consultation with LAs from the three nations (England, Wales and Northern Ireland). The proposed new model intends to give a more comprehensive reflection of the risks posed by food businesses (see Annex 1 for further details of the proposed model).

To address the challenges identified above, the proposed model incorporates three elements:

- A modernised risk assessment scheme to unify the way that LAs risk assess establishments (a new risk scheme).

- An assessment scheme using a matrix approach based on levels of inherent risk and compliance to identify the appropriate frequency for official control activity.

- Greater integration of intelligence as a driver of local authority regulatory activity and to inform the national understanding of food standards risk.

Additionally, due to the change in scoring approach the proposed model introduces a new definition for ‘broadly compliant’. The new definition of ‘broadly compliant’ is set out below:

- Definition under the proposed food standards delivery model: an establishment receiving an overall compliance risk assessment score of 3, 4 or 5.

“Non-Broadly Compliant” would therefore be any establishment that does not satisfy the above requirements. So, under the proposed food standards delivery model, if an establishment had a score of 1 or 2 as an overall compliance risk assessment score they would be regarded as non-broadly compliant.

Based on the findings from the initial pilot and the evaluation report, the FSA decided to adjust the proposed food standards delivery model. A summary of the changes is presented in Table 1.1.

| Lessons learned during the pilot in England and NI | Changes to the proposed model to be tested in Wales |

|---|---|

| England and NI pilot LAs found it difficult to identify non-compliances linked to allergens as the proposed risk assessment scheme did not include allergens as a separate element to be considered (allergens were embedded as part of other elements). | Introduced a new risk factor on allergens to the proposed risk assessment scheme. |

| England and NI pilot LAs did not find useful having Targeted Remote Interventions (TRIs) linked to a particular risk score under the matrix. They consider TRIs useful in some circumstances but prefer to consider their use on a case-by-case basis rather than a risk score. | TRIs are not part of the decision matrix anymore. The model changed to allow LAs to use remote interventions if and when they consider them to be appropriate. |

|

The England and NI pilot had a new category called No Actionable Risk (NAR), where no future intervention date would be allocated to the food business. This would mean LAs had to react to intelligence or complaints and visit the NAR business accordingly. After the pilot it was considered that the NAR category did not meet the Official Control Regulations (OCRs) requirement. OCRs require regular official controls to be conducted at an appropriate frequency based on risk. |

NAR was replaced by a new intervention frequency of 120 months. |

| England and NI pilot LAs asked for a way to prioritise the backlog of unrated businesses. |

The model introduced a desktop assessment (DA) for LAs to evaluate the inherent risk of new food businesses. The assessment should occur within 28 days of the business registering or the LA becoming aware of its operation. Information for this assessment is sourced from the documents completed by businesses when registering, such as the Register a Food Business (RAFB) completed by new FBOs (Food Business Operator) to comply with the Hygiene Regulations (Food Hygiene (Wales) Regulations 2006 and Article 6(2) of assimilated Regulation (EC) 852/2004), supplemented by other relevant information (for example from company websites, telephone conversations, emails, or questionnaires.) |

| There were several challenges identified with the intelligence function during the pilot, such as: what type of data should be shared, how frequently, what mechanisms to use and who should the data be shared with. | The Local Authority Intelligence Coordination Team (LAICT) have adapted their training and engagement with LAs to streamline this element. They have introduced, for example, regular intelligence newsletters that share trends and risks with LAs, and identified the type of data and frequency that they would like LAs to share. |

1.1.3 Local Authorities in Wales

There are 22 Local Authorities in Wales, and these are all unitary authorities. Unitary authorities operate under a single tier structure, with LAs responsible for all services in their area, including food hygiene and food standards.

Food standards official controls in Wales are delivered by a combination of dedicated food standards teams and teams that deliver both food hygiene and food standards controls. For the purposes of this report, the latter will be referred to as joint services. In joint services, food hygiene and food standards controls are sometimes delivered together by the same officer during one visit.

1.1.4 The pilot project

The pilot project in Wales commenced in September 2023 and ended in February 2024. The pilot tested the proposed food standards delivery model (see Annex 1 for further detail on the proposed food standards delivery model) with four LAs. Two LAs implemented the proposed delivery model (pilot LAs), and two LAs continued to work to the existing model detailed in the published Code (control LAs).

The aim of the pilot was to:

- demonstrate how the proposed new model applies to the Welsh context, and

- provide opportunities for LAs in Wales to participate and identify areas where the model can be made more suitable and applicable to the delivery of food standards official controls in Wales.

The proposed new model tested under the pilot does not amend the food standards legal requirements that FBOs must comply with.

The four LAs participating in the pilot project were selected based on their willingness to participate and in consideration of the following characteristics to ensure a representative sample:

- LAs from North and South Wales.

- LAs delivering food standards controls through a joint service (food hygiene and food standards delivered jointly) and others delivering solely via dedicated food standards teams.

As the pilot in Wales built on the lessons learned from the initial pilot in England and Northern Ireland, the FSA decided to use a smaller sample of LAs in Wales. The Wales pilot involved only four LAs meaning that the findings in this report cannot be completely representative of the Welsh LA population in total. However, the above criteria ensured that the different types of LA in Wales were represented in the pilot. Statistical tests have been included where possible however due to the small sample size differences between LA groups (control vs pilot) and between LAs more generally may be due to other factors and not necessarily due to the proposed model.

While all LAs in Wales are unitary, the selection represents the delivery method of food standards official controls in Wales: jointly or separately. Table 1.2 below indicates the characteristics of the LAs participating in the pilot:

| Pilot / Control | Delivery method | North Wales / South Wales |

|---|---|---|

| Pilot | Joint service delivery (food standards and food hygiene) | North Wales |

| Pilot | No joint service delivery (food standards) | South Wales |

| Control | Joint service delivery (food standards and food hygiene) | North Wales |

| Control | No joint service delivery (food standards) | South Wales |

1.2 Evaluation objectives and research questions

This evaluation aims to answer 5 questions:

- How did the proposed model perform compared to the current framework? What worked well and less well?

- What has been the experience of each of the stakeholders with respect to specific elements of the proposed model and the proposed model changes as a whole?

- What has been the effect on resources for each of the stakeholders because of the proposed model?

- What has been the overall effect of the proposed model? Did it deliver its objectives? Were there unintended consequences?

- What lessons were learned from piloting the proposed model?

The ICF study team developed an evaluation matrix to answer the questions, shown in Table 1.3 below.

| Evaluation question | Data collection method | Examples of data collected / indicators |

|---|---|---|

| 1. How did the proposed model perform compared to the current framework? What worked well and less well? |

Two waves of interviews with LAs Interviews with FSA staff A series of meetings with FSA staff Quantitative data gathered by the FSA |

LAs and the FSA perspective on ease of use of the new approach Enablers / barriers to using the new proposed model (IT, skills, resources, location, type of food business) LAs and the FSA perspective on the comprehension of the proposed model |

| 2. What was the experience of each of the stakeholders with respect to specific elements of the proposed model and the proposed model changes as a whole |

Two waves of interviews with LAs Interviews with FSA staff A series of meetings with FSA staff |

Perceptions by LAs on quality of training received to prepare for proposed model Opinion of users of the proposed model on ease of communication, frequency, and quality of data The FSA perceptions on the proposed model |

| 3. What was the effect on resources for each of the stakeholders because of the proposed model? |

Two waves of interviews with LAs An online meeting with FSA staff |

Opinion on the adequacy of resources for implementing the proposed model Changes to how LAs use resources Changes made by LAs and the FSA to adapt to proposed model (costs, staff, IT systems, skills) |

| 4. What was the overall effect of the proposed model? Did it deliver its objectives? Were there unintended consequences? |

Two waves of interviews with LAs Interviews with FSA staff A series of meetings with FSA staff Data generated by FSA evaluation plan |

LAs perceptions of impact on the identification of non-compliance and actions to resolve Frequency and type of inspections Perceptions of consistency under the proposed model LAs views on potential unintended consequences |

| 5. What lessons were learnt from the pilot? |

Data generated by evaluation plan Interviews with FSA staff A series of meetings with FSA staff |

Adaptation of the pilot using data generated and analysed if needed Use of lessons learned from the pilot to inform the proposed model |

1.2.1 Methodology

1.2.1.1 Phase 1: Scoping

The scoping phase included:

- Review of existing documentation, including the updated pilot guide for the proposed new food standards delivery model in Wales, and other relevant documents outlining the activities and outcomes to date.

- Interviews with FSA staff to understand the pilot objectives, activities and progress to date, and to inform the evaluation methodology. Three interviews were conducted. Interviewees included members of the Wales FSA team, the FSA Local Authority Intelligence Coordination Team (LAICT) and the FSA Analytics Unit.

- Definition of the evaluation framework, including developing the interview guides and finalising the method.

1.2.1.2 Phase 2: Data collection

The data collection phase included:

- Two rounds of interviews with LAs to understand their expectations, their experience with the process including any challenges, as well as to document the changes implemented due to the proposed model. The first round was completed before the start of the project between June and July 2023 and the final round was completed a few weeks after the pilot project had ended in March 2024. Interviews were held with all four LAs participating in the pilot. The interviews followed a semi-structured format and were recorded.

- A series of regular meetings with the FSA to share progress updates and discuss any issues which had arisen, as well as defining timelines.

- Interviews with FSA staff at the end of the pilot, to capture their experience with the process. Two interviews were conducted, one with a member of the FSA in Wales and the other with a member of the Regulatory Compliance Division (RCD) leading on the England and Northern Ireland roll out.

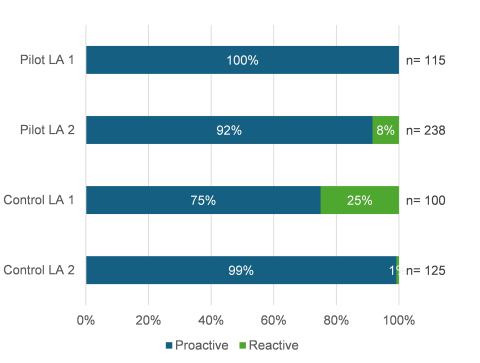

- Quantitative data collected by the FSA Analytics Unit (AU). AU collected monthly data (between September 2023 and February 2024) from all participating LAs (control and pilot groups) in a standardised format. LAs self-reported this data during the pilot period. Data collected included risk scores from every inspection, data on reactive (intelligence led) vs proactive (programmed) interventions and compliance scores. For pilot LAs the risk assessment data was provided for both the current model and proposed model. For control LAs the risk assessment data was only for the current model as they did not operate under or see the proposed model.

The pilot LAs carried out 353 interventions (of which, full details were given for 198). The control LAs carried out 225 interventions (of which, full details were given for 184). These figures exclude any premises visited by LAs that were found to be permanently closed. It should be noted that all data shown in this report is for premises that were visited by LAs during the pilot period only, data is not shown for the full set of premises within an LAs area.

1.2.1.3 Phase 3: Data analysis

The data analysis phase was continuous through the life of the pilot project. The data analysis phase included:

- A series of meetings with FSA staff to share the findings collected, ensure a common understanding of the main challenges and enablers, and refine the evaluation data collection tools. It also included meetings with FSA Analytics Unit to understand their data collection process to integrate the data into this report.

- Analysis of the evidence collected such as interview responses and a review of documents provided by the FSA. Thematic analysis was used to analyse the interview responses in line with the evaluation questions. The ICF team collated and assessed the evidence based on the themes in this report.

- Analysing and integrating the quantitative data collected by the FSA Analytics Unit. Chi-squared tests were performed at a 5% significance level.

Limitations:

- The sample size (4 LAs) was small and the length of the pilot (6 months) short. This meant that there were limitations to the representativeness of the data collected (in terms of LA characteristics, mix of premises types, and period of time for the LA to complete interventions).

- As mentioned in section 1.1.4, the small sample size of 4 LAs for the pilot project meant that the results were not representative of all LAs in Wales. While statistical tests have been used where possible, it is important to note that differences between LA groups (control vs pilot) and between LAs more generally may be due to other factors and not necessarily due to the proposed model.

- The small sample size should also be noted when considering the qualitative findings as there was a limited number of individuals involved in piloting the proposed model.

- Further, the short timeframe of the pilot (6 months) made it more difficult to run robust statistical analysis with which to draw conclusions. It also meant it was not possible to observe evidence of changes in compliance of targeted premises.

- This pilot project built on the positive findings and lessons learned from the initial pilot whilst testing the proposed model in the Welsh context. Therefore, the shorter timescale and small sample size were deemed appropriate for this purpose.

Despite these limitations the evaluation team were able to assess the fit of the model in the Welsh context and identify any unintended consequences.

2.1 Baseline

A baseline round of LA interviews was conducted before the pilot. The purpose of baseline interviews was to compare the changes between the baseline and the end of the pilot, as well as to observe whether the control LAs evolved in a different manner to the pilot LAs. The interviews explored how LAs were currently implementing the existing model, challenges faced and expectations around the pilot.

2.1.1 Approach to current delivery of official controls in Wales

There are two different approaches within LAs to the delivery of official food controls in Wales: those LAs that deliver all food standards official controls through a dedicated food standards team, and those LAs that operate a joint service delivering food hygiene and food standards official controls via a single team.

- No joint service delivery (food standards): These LAs deliver food standards controls separately to hygiene controls. They explained they assess and identify their food standards interventions following the Code but will often emphasise high-risk premises. Their teams would assess business risk and allocate the interventions at the beginning of the year. Their sampling and project priorities determined on a local or regional basis can also guide the remainder of the work they do.

- Joint service delivery (food standards and food hygiene): These LAs use the same team to carry out food standard and food hygiene inspections. When they can, they aim to do joint inspections. For example, for medium and low risk premises, LAs would decide whether a food standard inspection is needed or not while reviewing the food hygiene inspection programme. As food hygiene controls are often delivered more frequently (every 6 months) than food standards (high risk being every 12 months), food hygiene inspections often dictate the timings and selection of establishments for food standard inspections. Sometimes, for specific high-risk food standard premises, LAs would prioritise food standards and visit them. The LAs interviewed perceived that, since they started delivering food standards and food hygiene inspections jointly, they are more efficient in their way of working. They mentioned they are able to carry out more interventions than before. However, they also explained that not all officers perceive themselves to be capable to carry out food standards. They said officers from the food hygiene team had a steep learning curve to get the level of technical knowledge necessary to deal with some of the complexities of food standards.

During the interviews, the LAs discussed specific practices around key areas:

Identification and resolution of non-compliances

LAs commonly identify non-compliances through inspections, complaints, or sampling activities. High-risk premises are prioritised, with notification to businesses upon finding non-compliance. LAs would recommend remedial actions to follow up on how the business has addressed the non-compliance. These vary based on severity of non-compliance, from simple fixes with photographic evidence to re-visits or prosecution. However, resource constraints and backlogs due to the COVID-19 pandemic have strained inspection capacities.

Use of Intelligence

LAs use intelligence, gathered from various sources, to help identify any potential non-compliance and risk areas. Two of the LAs included in the pilot explained they were already effectively incorporating intelligence into their work. One of these two LAs is the regional intelligence lead for Wales. However, the other two LAs mentioned using intelligence was challenging for them as it was time-consuming to record and share intelligence in line with relevant requirements. They also perceived the information they held or received was not always complete. Overall, the four LAs that participated in the pilot project perceived intelligence-led approaches were beneficial for resource allocation and risk targeting and would like to use more of these approaches in the future.

Sampling activities

LAs explained that food sampling priorities are set on a national, regional, and local basis. This happens annually. At national level, the yearly sampling priorities are selected following criteria that the FSA in Wales determines. Some LAs supplement this information with relevant data from the National Food Crime Unit (NFCU). On a regional basis, LAs emphasised there were some regional differences between North and South Wales when determining sampling priorities. As such, LAs in Wales also coordinate with their regional areas to set priorities. Recently, local budget reductions meant LAs rely more on knowledge sharing and suggestions on what to focus on, working as a region.

Adaptations to the current model

LAs explained they are making small adaptations to the existing model for better efficiency and flexibility. Some examples of these adaptations included seeking flexibility in business rankings (in terms of high, medium or low risk), identifying improvements to make the process reviews more efficient, and incorporating lessons learned from the pandemic into their practices. However, the four LAs explained they would appreciate the Code having more flexibility to account for regulatory changes and the evolving food sector.

In summary, the four LAs perceived that while the existing food standards delivery model in Wales had demonstrated effectiveness, the current delivery model had some challenges related to its rigidity (e.g. reduced flexibility could lead to LAs to miss allergen issues due to changes in menus or suppliers), not being up to date with regulatory changes (e.g. new types of establishments or ingredients) and the allocation of resources. LAs emphasised they would prefer the delivery model to focus on outcomes rather than mere inspection completion numbers. As such, LAs were excited to test the proposed model hoping it would address some of the challenges identified.

2.2 Research Question 1: How did the proposed model perform compared to the current framework? What worked well and less well?

The proposed model operated well, was fit for purpose and was generally easy to understand and use.

Both pilot LAs perceived that the proposed model addressed the limitations identified of the prior model. The proposed model provided a more balanced assessment of the food businesses taking account of both the level of inherent risk and the level of compliance displayed. The proposed model ensured the next official control after significant non-compliance identification are a priority, allowing LAs to target their resources towards those visits. This is more in line with how the LA feels interventions and the food standards service should be operating and was motivational for the team.

The proposed risk scheme was seen as beneficial and the addition of the standalone allergen score was particularly valuable in assisting LAs to give allergens proportional focus within interventions and target resource where the risks are highest.

The proposed decision matrix which indicates the intervention frequency for businesses was also seen as beneficial.

Despite the positive reflections, LAs found some of the terminology lacked clarity which made it challenging to implement the proposed risk scheme in a consistent manner. Key areas where more clarity was expected were:

- Guidance on the allergen scoring criteria and the thresholds between scores.

- Expanding on the risks of online distribution within the code and guidance.

- Definitions and interpretation of key terminology and phrasing.

This section presents the findings showing how well the proposed model worked. It assesses whether the model was fit for purpose, its ease of use and any challenges identified in using the proposed model in relation to its application and operation. This section also analyses the context in which the pilot was delivered, assessing the enabling factors and barriers faced during the implementation of the pilot project itself. The effects of the proposed model, namely whether it achieved its objectives, are discussed in section 2.5

2.2.1 Appropriateness of the proposed model (fit for purpose)

Both pilot LAs perceived that the proposed model was fit for purpose, and was an improvement in comparison to the current model as it addressed the limitations identified of the current model. LAs perceived that the proposed model provided a more balanced assessment of the food businesses taking account of both the level of inherent risk and the level of compliance displayed. However, both LAs noted that the accompanying guidance to implement the proposed model could be improved (see section 2.2.3).

The rest of the section explores the appropriateness of the three elements of the proposed model (the risk scheme, the decision matrix, and the inherent risk desktop assessment). Two of the elements were considered positive, however there were concerns about the inherent risk desktop assessment for new businesses.

2.2.1.1 The proposed risk scheme

Pilot LAs welcomed the proposed risk scheme. LAs reported that the proposed model allowed for more flexibility than the existing one, enabling them to effectively target resources to higher risk establishments. This is because the proposed model combines the assessment of inherent risk of the establishment with a more comprehensive assessment of the establishment’s compliance (through assessment of four factors instead of the current two). The way the two risk elements are combined is also improved as the proposed model uses a matrix approach to average the scores. It also includes an assurance rule whereby any compliance factor given a score of 1, the lowest level of compliance, results in an overall compliance score of 1 as the averaging process is ignored. This assurance rule better accommodates the high risk posed by non-compliance in the overall scores in comparison to the current model where scores are added together. The proposed risk scheme gives a more balanced assessment, allowing the level of compliance within a business to be a more prominent part of the rating rather than focusing primarily on inherent risk. It allows for more granularity in the risk assessment process.

While under the current model, LAs consider the risks of allergens and act on all non-compliances found relating to allergens, all four LAs (pilot and control) perceived that, as mentioned in the baseline (section 2.1.1), the current risk scheme did not sufficiently reflect the high risk posed by allergens.

As such, pilot LAs found the way the proposed allergen risk score was incorporated into the risk scheme particularly beneficial. One pilot LA felt that the standalone allergen score helped to emphasise the importance of the food standards service within overall food safety.

2.2.1.2 The decision matrix

Overall, it was reported by both pilot LAs that the proposed decision matrix worked well and there were some benefits to the increased number of risk categories and intervention frequencies such as the more accurate prioritisation of risks and ability to reduce resourcing focus on food businesses who are considered low risk and highly compliant.

The decision matrix was reported to be easy to use. However, there was an adjustment period needed before food standards officers felt comfortable and confident with the new risk levels within the proposed decision matrix. One LA commented that, initially, the proposed decision matrix was challenging for them. This is because the proposed decision matrix contains 10 risk frequencies compared to the current three. They had to switch their way of thinking from the prior ‘A’ high risk, ‘B’ medium risk and ‘C’ low risk to a different fit within the risk categories. A period of transition is expected given the length of time the current model has been in use (see section 2.3.3 for the FSA response and preparation on this).

Pilot LAs were also concerned about the change in the frequency of visits for some establishments. One LA was particularly concerned about large manufacturers. While large manufacturers are largely compliant, the LA was keen to maintain contact and rapport with the FBOs teams – as one non-compliance (even if unlikely) could have large consequences. Under the current model all manufacturers are classed as high-risk meaning that they should receive an annual inspection from the LA. The proposed model, however, showed that the intervention frequency for large manufacturers only decreased for two manufacturers and increased for four, out of a total of nine manufacturers, as shown in section 2.5.1.5. It should also be noted that the frequencies generated by the risk matrix represent a minimum frequency of intervention and LAs have the flexibility under the Code to bring interventions forwards if deemed appropriate.

2.2.1.3 New businesses: inherent risk desktop assessment

The proposed model also introduces a desktop assessment (DA) to assign new establishments with an estimated inherent risk and assist in prioritising initial inspections of new businesses. The DA uses multiple data sources, including Register A Food Business (RAFB), other documentation that may be used when registering a food business as well as publicly available data sources such as a business’s website. The proposed DA aims to enable more effective prioritisation of new business initial inspections and provide a structure to support LAs with an increasing backlog of unrated new businesses. The mandating of desktop assessments will be considered as part of any potential consultation prior to consideration of providing advice to Ministers regarding a potential wider roll out of the proposed model in Wales. Both pilot LAs were asked to use it during the pilot period. Further details on this mechanism are available in Annex 1. The aim is to prioritise food businesses for initial intervention based on their perceived inherent risk.

Of the two pilot LAs, one found this new process burdensome as they perceived that it added paperwork without providing additional insights. They mentioned they were already following a similar process internally; however, they explained that the DA took longer for them to complete without adding additional value. They recommended including additional questions in the business registration form to streamline the inherent risk assessment process.

The other LA did not comment on this.

2.2.2 Ease of use of the proposed model

Both pilot LAs found the proposed model easy to use once they had built up their confidence and understanding. They emphasised that the change is only about frequency of interventions and how they assess risks and compliance, but the interventions remain the same.

One pilot LA appreciated the increased capacity to prioritise revisits to non-compliant food businesses through the new proposed 1-, 3- and 6-month intervention frequencies. This was identified as a positive feature, as under the current model revisits are scheduled but often given lower priority compared to priority interventions already scheduled. Due to resource constraints, these revisits are often delayed. The proposed model ensures revisits after a non-compliance are identified as a priority, allowing LAs to target their resources towards those visits. This element allows LAs to focus on addressing non-compliances quickly rather than focusing on the number of interventions that have taken place. This is more in line with how the LA feels interventions and the food standards service should be operating and was motivational for the team.

The proposed model was viewed as being compatible with the way that LAs perceived food standards should operate, as it identified the major risks and enabled the LAs to prioritise revisits to seek to resolve non-compliances.

2.2.3 What were the enablers (what worked well) and the barriers (what worked less well) for implementation of the proposed model?

The FSA support was a key enabling element in the success of the pilot. The support received from the FSA before and during the pilot was reportedly very useful to LAs. The pilot opened a line of informal communication between the FSA and the LAs, where they could collaborate to solve issues together.

The FSA were identified as being responsive to communication. LAs felt they had a ‘point of contact’ where their queries would be addressed. More detail on training and support provided can be found in section 2.3.1.2. One LA reported conducting their own in-house consistency exercises to help provide further reassurance.

Despite the benefits identified and the positive feedback around the proposed model and the FSA’s support both pilot LAs identified one main barrier to consistent implementation and areas for improvement – around terminology used. There were a number of areas within the risk scoring guidance which were open to interpretation and further definitions and guidance are needed, namely:

- Scoring of premises which pose ‘no allergen risk’ in the view of LAs (e.g. only selling pre-packed food or producing single-ingredient foodstuff like honey). Clarity was needed on how to give an allergen score for premises who have ‘no allergen risk’ and therefore no allergen information or process.

- Clarity around thresholds between the scores for the allergen information risk score (for example between a score of 1 and a score of 2). It was unclear for the LAs what the tipping point was between these two scores. The LAs felt that any level of non-compliance on allergens poses a high-level of risk to consumers. This clarity is needed to avoid food businesses being scored more harshly than necessary, impacting their intervention frequency.

- One LA identified that online distribution is not sufficiently discussed within the current guidance. This was particularly the case for the wording ‘scale of supply and distribution’ and whether online distribution should be considered within this. The LA highlighted that although often online distribution is at a local level the online format means that distribution could be national or international. The LA had noted a substantial difference in how their officers were scoring the inherent risk of FBOs who distribute online.

- Definitions and increased clarity around the wording ‘wide range’ and ‘limited range’ within the phrase ‘Establishments responsible for producing or labelling a wide range [or limited range] of foods’ within the Ease of Compliance criteria. The LA gave the example of a manufacturer who produces 25 different ready meals, are they considered to be producing a wide range or would they need to produce a range of different products in addition to ready meals to be wide range.

- Better links to existing definitions and increased clarity around key words such as ‘local’ to ensure consistency in approach and confidence in the continuity of definitions between the current model and the proposed model.

Both pilot LAs reported that the proposed model was fit for purpose but that increased clarity and guidance covering the above identified issues would increase their confidence in using the proposed model and the consistency of risk assessment and management across Wales. This was under the context of limited resource capacity meaning that if food businesses were not identified as needing priority intervention they could end up having limited contact with the LA.

2.3 Research Question 2: What has been the experience of each of the stakeholders with respect to specific elements of the proposed model, and the proposed model changes as a whole?

The experience of each stakeholder (LAs and FSA) was overall very positive.

- LAs decided to join the pilot because they wanted to understand and influence the proposed model with FSA, and to be able to adapt early to it. Their experience during the pilot met these expectations.

- LAs reported that they received all of the training and support prior to and during the pilot period that they would have liked. They found the food business “risk assessment” scoring scenario exercise and discussion to be particularly beneficial for increasing understanding and highlighting areas of interpretation.

- There were few challenges reported regarding implementation of the proposed model.

- One LA highlighted concerns around the database mapping conducted to convert the risk score of the premises on their databases to the new risk assessment scheme of the proposed model.

- The proposed model had no impact on use or sharing of intelligence, sampling activities or use of remote inspections (these were aspects of the initial pilot but were not the main focus under the Wales pilot).

- LAs reported no unintended consequences from the pilot or the proposed model.

- The FSA reported that the proposed food standards model had run as expected and overall, the pilot had been a positive experience. They noted the request for further guidance and clarification on certain areas.

This section analyses the experience of the different stakeholders engaged in the pilot and their perspective on the new proposed model. The section addresses the reasons for LAs to join the project, considers LAs’ attitudes towards the pilot and finally summarises the FSA experience of the pilot.

2.3.1 LA experience

2.3.1.1 LA motivations for joining the pilot

LAs decided to join the pilot project for a number of reasons. All LAs stated that the decisive factors for joining were their willingness to influence the model to ensure it fits their needs, and the capacity to anticipate and adapt to the changes as soon as possible. LAs appreciated having the opportunity to start early and work on this new proposed model with the FSA. This shows that all LAs participating in the pilot, whether testing the proposed model or in the control group, had already identified some challenges with the prior model, were willing to try the proposed one, and to collaborate with the FSA to ensure a smooth transition. They all voluntarily expressed an interest in participation after an invitation from the FSA was sent out to all LAs in Wales.

2.3.1.2 Preparation for implementing the proposed model

The FSA supported LAs prior to and during the implementation of the pilot. Section 2.2.3 discussed that LAs found this support to be one of the enablers of the pilot process. Preparation activities carried out included:

- An in-person contact day in Cardiff with the FSA to gain understanding of the proposed model, including a pilot LA from the initial pilot explaining their experience and an exercise where everyone individually rated a food business scenario and then discussed the differences in their scoring. This highlighted some of the interpretation issues (discussed in section 2.2.3).

- FSA visit day at the LA premises where the FSA spoke with all staff involved in the pilot and answered any queries. The LA team leads really appreciated this approach as it meant questions could be asked directly and avoided all of the information being passed to the lead officer and then cascaded down to the rest of the team.

- Regular contact with the FSA team to respond to queries.

Both LAs reported receiving all of the training and support that they would have liked. They found the scenario exercise from the contact day particularly useful. As a result, one of the pilot LAs decided to implement a consistency training with their food standards team, which included a scoring of a scenario exercise (this is discussed further in section 2.3.1.3 below). The FSA team member running the training felt that it went well, there was good engagement from the LAs in the activities and many clarification questions were asked at this stage. They also felt that the scenario exercise was particularly useful.

Support from the FSA continued throughout the pilot in the form of monthly joint catch-up meetings with the two pilot LAs and some individual meetings. These meetings facilitated sharing of experiences and learning from all parties, noted as a benefit by the two pilot LAs. The pilot LAs reported that having one point of contact within the FSA had been beneficial and useful as it ensured clearer messaging and allowed for more open sharing of issues.

Online meetings were held with the control LAs prior to the start of the pilot to establish and discuss the data submission aspects that the control LAs would be required to complete. The control LAs were also offered regular meetings but did not take up this offer as they did not require any additional support from the FSA as they were operating as normal under the current model.

2.3.1.3 Implementing and working with the proposed model

Both pilot LAs trained some, or all, of their officers to work with the proposed model. One pilot LA provided additional support to their team for the implementation of the pilot:

- Setting up of a Microsoft Teams site to share guidance and provide space for their team to ask questions.

- Fortnightly catch ups with the LA team to discuss how the pilot model was working.

- Running of ‘consistency exercise sessions’ where the LA team could discuss any interpretation issues or queries to ensure a level of consistency across the team for scoring of premises. These sessions reduced in frequency through the pilot period showing an increase in confidence in implementation of the proposed model. The LA found these exercises to be very useful and are considering running a session annually regardless of the outcome of the pilot.

2.3.1.4 Challenges to implementing the proposed model

Overall, both pilot LAs reported not having any major challenges with implementing the proposed model. They both noted that the team required training and an adjustment period, which they expected. Once the confidence and understanding was built there were no major questions.

One LA identified issues with the initial mapping of their database (Initial exercise conducted by the FSA to define the new intervention frequencies for each establishment at the start of the pilot.) and resulting initial risk scores. This LA team were very familiar with their ‘A’ rated premises so expressed concern when not all these were flagged as priority interventions after the mapping to the proposed model was completed. The LA gave one example where a manufacturing site had not been rated a priority due to its high level of compliance, but they considered it to be higher risk as it produces allergen sensitive products and distributes them widely. The mapping system used for the pilot primarily used the overall business type e.g. ‘manufacturer’ to map food businesses to the new proposed risk matrix and therefore did not consider any contextual information. However, this is only a risk during the initial set up stages of the proposed model as the systems are converted. Once outliers have been identified and interventions resume this risk decreases. The FSA response to this ahead of the England and Northern Ireland roll out of the proposed model can be found in section 3.2.1. This shows a risk of the current database mapping system which only considers the food business type.

The LA noted that for their LA, due to having a smaller and more experienced team, knowing which premises should be a priority was easy but that for other LAs, with many more premises to cover, the initial mapping may lead to rating some premises wrongly. The FSA has noted this risk and is reflecting on how to mitigate it (see section 3.2.1).

2.3.2 Other aspects of food standards operations

The Welsh pilot of the proposed food standards delivery model did not include a directed focus on piloting use of intelligence, directed sampling or targeted remote interventions (elements tested in the initial pilot, see section 1.1.1 and Table 1.1). There was potential for directed sampling and intelligence tasking to be issued but these did not materialise throughout the pilot. The LAs were able to use remote interventions as and when they considered they were appropriate.

These elements were discussed with LAs to understand if the proposed model had had any unintentional impact in these areas. It was found that the pilot did not impact on levels of sampling, remote interventions or use of intelligence for all four of the LAs.

2.3.2.1 Intelligence

There is a very wide range of understanding and use of intelligence across the four LAs. Interview data showed that intelligence is typically gathered through reports on the intelligence database system (IDB), reports from the FSA NFCU, complaints from other sources, sampling data, discussions within the regional sampling groups, discussions at the food standards expert panel, and the export/import control groups.

Baseline data showed that the two pilot LAs used and shared less intelligence than the two control LAs before the pilot started. Data from the pilot period shows that the control LAs submitted a total of 14 intelligence reports to IDB and the pilot LAs submitted a total of 4 reports. However, to put this in context one control LA is the regional intelligence coordinator for Wales meaning that they already submit above average volumes of intelligence as part of their day-to-day intelligence role. The other control LA specified in their baseline interview that this year they were focusing on improving their use and sharing of intelligence. On the other hand, the two pilot LAs noted that they struggle to upload intelligence onto IDB due to resource constraints and lack of confidence with the IDB system. It is therefore likely that the difference in intelligence reporting during the pilot period between the pilot and control LA was as a result of the specific LAs pre-existing relationship with intelligence rather than being caused by the proposed model.

LAs noted in interviews that they do act on intelligence reports where they are relevant.

One LA stated that more clarity is needed in some intelligence reports sent and received by LAs to make sure they include all necessary details to ensure that LAs can use intelligence to guide their work and support them in identifying the likelihood of the risk or threat identified. All four LAs indicated that they would like to use intelligence more in the future.

2.3.2.2 Sampling

Qualitative data from interviews shows that the four LAs are involved in regional sampling groups and follow the regional sampling plans. LAs confirmed in interviews that this set up had not changed during the pilot period and many of the sampling plans were set prior to and covered the whole pilot period.

The proposed model did not have an impact on sampling for the four LAs.

2.3.2.3 Remote interventions

All four of the LAs showed hesitancy around the use of remote interventions (RI). No RI’s were conducted as part of the pilot but there were some examples of where LAs were beginning to use RI style interventions. One control LA gave the following example: directing a non-qualified officer to check that a simple non-compliance had been rectified (dependent on type of non-compliance) or do a selected ‘C’ rated food business intervention (e.g. clothing retailers with pre-packed sweets at the counter) using a self-assessment questionnaire, this example is under the current model and was not used during the pilot period.

Joint service LAs noted that when joint interventions were needed, they would always have to be done in-person to satisfy the Food Hygiene Rating Scheme (Food Hygiene Rating (Wales) Act 2013). Single service LAs were also hesitant as they felt that in-person interventions were a better way to guarantee an accurate scoring and that FBOs may not mention something that they do not see as relevant but that the trading standards officer could find if they were in-person at the premises. The responsibility for protecting the public from risk impacts upon trading standards officer’s confidence in implementing RIs rather than in-person interventions. Confidence is the main barrier to use of RIs.

When asked in interviews where LAs felt RIs could be appropriate or where they may wish to use them in the future each LA did identify examples of where they could be used. Examples given included checking on updated risk assessments or an allergen matrix via email. The two pilot LAs identified that RIs could be used with the short frequency interventions but they stressed that this would depend on the nature of the non-compliance identified.

2.3.3 The FSA experience (Food Standards Agency reflections and response)

2.3.3.1 Food Standards Agency reflections on the pilot

The FSA reflections on the implementation of the pilot were positive. The staff involved in the implementation and working regularly with the LAs shared that the regular communication with LAs had been the key to the success of the project.

The FSA perceived that a challenge could be LAs reactions to changes in frequency of interventions, especially a potential increase in the number of interventions (this perception was based on engagement with LAs across Wales prior to the pilot). However, after risk scores were mapped to the proposed model the new risk frequencies showed that this was not the case (See section 2.5.1.5).

Another challenge identified by the FSA was the administrative burden for LAs caused by the extra data submission spreadsheets for the pilot monitoring (this included additional data submissions and the use of a scheduling spreadsheet which acted as a temporary management information system (MIS) to guide the work during the pilot, this will not be part of a wider roll out). The FSA noted that both pilot and control LAs in the Wales pilot were funded to submit this data and the extra data submissions would not be part of any potential roll out in Wales. Additionally, the FSA recognised that the proposed risk rating scheme and the new frequencies would take LAs some time to adjust to, especially as the current model has been in place for a long period of time.

The FSA also noted the selection of a shorter time period (six months instead of a year) was the right balance of testing without additional burden. As the FSA had already tested the effectiveness and amended the proposed model in England and Northern Ireland, the focus of this pilot evaluation was to ensure the refined proposed model worked in the Welsh context, and to test the new elements of the proposed model such as the allergen score.

2.3.3.2 Food Standards Agency reflections on the proposed model and on a potential further rollout

The FSA reported that the proposed food standards delivery model had run as expected. The LAs had adapted well to the proposed model with fewer clarification questions asked of the FSA during the pilot period than expected. The LAs did not identify any unintended consequences of the pilot or the proposed model.

The FSA identified that the interpretation and consistency issues (discussed in section 2.2.3) were the biggest challenge to effective implementation of the proposed model.

The FSA acknowledges that a period of transition will be needed to ensure LAs can acclimatise to the proposed new model if rolled out. The FSA have developed a suite of training packages to help LAs become familiar with the new model (these are currently being delivered to LAs in England and Northern Ireland following introduction of the new model there).

Throughout the pilot period the Welsh FSA pilot team shared feedback with the FSA’s Achieving Business Compliance (ABC) team to ensure the recommendations are reflected on the England and Northern Ireland wider roll out (and on the potential roll out of the proposed model in Wales). The FSA Welsh pilot team and ABC team have also been working closely with the performance management team and the Audit team to ensure other FSA services appropriately take account of any upcoming changes (and the pilot period itself). This reflects the FSAs awareness that the proposed model would take some time for LAs to adjust to. This has led to the development of a new set of KPIs relating to the proposed model which will be introduced if the proposed model is rolled out in Wales.

In light of these conversations, the FSA has noted the request for more guidance on:

- Scoring of premises with no allergen risk.

- Difference between scores (particularly between a 1 and a 2) for allergen criteria (this has been covered in the England and Northern Ireland guidance and associated training).

- Definitions on specific phrasing used (e.g. online and wide vs limited range has been covered in the England and Northern Ireland guidance).

- Implementation of the proposed model for LAs operating joint services, explaining the scheduling of interventions through the comparison of intervention frequency reports for food standards and food hygiene. Verbal guidance was provided during the pilot period, but written guidance is identified as beneficial.

- Service planning due to the need to have a more dynamic team with the proposed shorter intervention frequencies (this was also a key point from the initial pilot and non-prescriptive guidance has been developed on this).

The FSA mentioned that the proposed model would require a balance between having prescriptive guidance and allowing flexibility for food standards officers to use their knowledge and experience to risk rate a food business. Further, the training and preparation for a full roll out would be different to the pilot preparation (see section 3.2.1).

2.4 Research Question 3: What has been the effect on resources for each of the stakeholders because of the proposed model?

LAs discussed resourcing in terms of:

- The pilot period: it was reported that there was no change in resourcing caused by the pilot or the proposed model during the pilot period. One LA made a resourcing change during the pilot period, and this was to support efforts to reduce the backlog of interventions not due to the proposed model.

- A potential wider roll out: concerns were raised around how to effectively plan and justify resourcing within annual service plans under the proposed model, particularly in light of external financial pressures on LAs.

It was mentioned that the proposed model would not address the shortage in resources and the backlog in inspections.

The answer to this question focuses on the changes made by the LAs and the FSA to adapt to the proposed model. This includes changes linked to the implementation of the pilot, and changes to resources linked to the delivery of the proposed model.

2.4.1 Resourcing the pilot

The pilot and proposed model did not affect the resourcing needs of the LAs. Across the four LAs resources have changed very little during the pilot process. The pilot leads within the LAs have stayed consistent (although one has had a change in job title with no impact on the food standards role).

Only one LA experienced any change in resources during the pilot period. The LA brought in a consultant in December 2023 to assist with solving the backlog of interventions. This consultant did participate in interventions under the pilot model but the LA emphasised that this change in resource would have happened regardless of the pilot and was not caused by the proposed model.

The FSA’s role in supporting the LAs in the preparation and throughout the pilot was as expected. The FSA received fewer queries than anticipated.

2.4.2 Resourcing for a potential wider roll out of the proposed model

Both pilot LAs expressed concerns around resourcing for the potential future roll out of the proposed model due to the potential for increases in inspection frequencies and concerns around service planning (however, they did not require additional resources during the pilot).