Effects of PPDS labelling requirements - PPDS evaluation

This chapter covers the effects Prepacked for Direct Sale (PPDS) labelling requirements have had on consumers with Food Hypersensitivities (FHS), Food Business Operators (FBOs), and Local Authorities (LAs). Specifically, the chapter explores the effects on: • the availability of ingredients information for consumers and the reported impact this has had on their purchasing behaviour and quality of life • the costs and practices of FBOs • the time spent by LAs conducting inspections and tasks associated with inspections.

Consumers

Most commonly, consumers with FHS reported no change to their perceptions and behaviour. Some of the findings from this research suggest that the implementation of PPDS labelling requirements has had a positive effect on the perceptions of some consumers and the behaviours of a minority, however, these were not experienced by the majority.

Where there were some positive changes, this was in relation to the perceived availability of ingredients information and confidence in buying PPDS foods, and more commonly seen in younger consumers. Only a minority of consumers reported purchasing PPDS foods more often since the introduction of PPDS labelling requirements. Qualitative research suggests this is likely to be due to concerns about the risk of cross-contamination.

Perception of availability of allergen information

Consumers with FHS were roughly evenly split in their perception of whether the availability of information (needed to identify a food that may cause an unpleasant reaction) had improved since the introduction of PPDS labelling requirements. Whilst 42% said that in their opinion it had improved, 37% said they felt it was the same. Moreover nearly a fifth (18%) said that they didn’t know, indicating that these consumers have not noticed the availability of information changing suggesting a potential lack of impact. Only a very small proportion (3%) felt the availability of information had worsened.

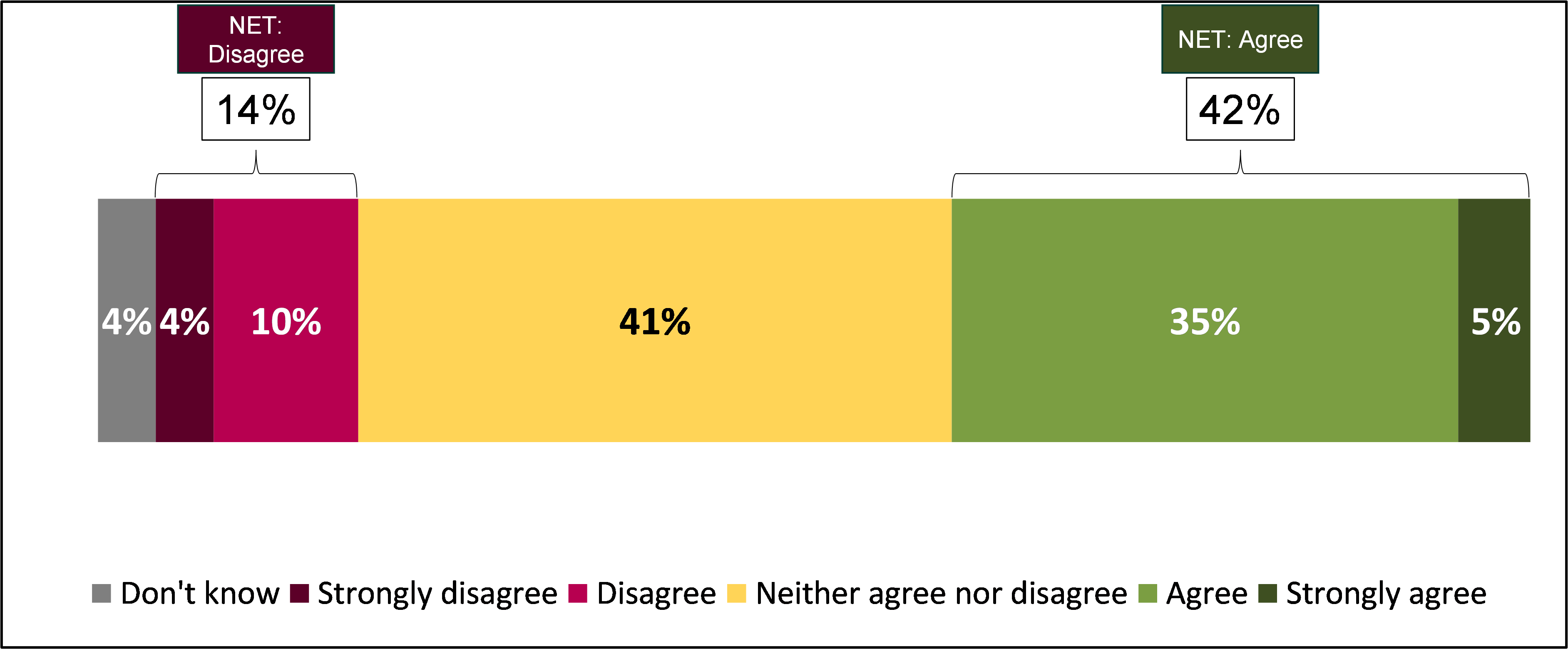

Figure 6.1 Change in the availability of information needed to identify a food that may cause an unpleasant reaction

E1. Since the introduction of PPDS labelling requirements in October 2021, has the availability of the information you need to help you identify if a PPDS food might cause you or your child a bad or unpleasant physical reaction gotten better, worse, or remained the same? Base: Consumers that buy PPDS foods (1639).

There was no difference by country in the proportion of consumers that reported an improvement in the availability of ingredient information since the PPDS labelling requirements were introduced (England: 42%, Northern Ireland: 38%, Wales: 39%). However, younger consumers aged between 18 and 34 were more likely than those aged between 34 and 64 and those aged 65 and over (52% vs 40% and 40% respectively) to report an improvement in the availability of information, as well as those that purchased PPDS foods sometimes or often who were more likely than those that purchased PPDS foods rarely or never (51% vs 36%). Consumers who only had an allergy/ intolerance to a regulated allergen rather than only a non-regulated allergen were also more likely to report an improvement (43% vs 27%).

When discussing the impact of improved information availability on PPDS labelling during the qualitative interviews, many consumers spoke about how they felt better equipped to make informed purchasing decisions. Consumers often attributed this to the emphasis of allergens on PPDS labels, as this made it quicker and easier for them to identify ingredients that could cause them an unpleasant or life threatening reaction.

“They allow you to make a choice with a bit more confidence … The use of the bold print and italic letters is useful in helping you to make an informed choice.”

Consumer, England, Severe hypersensitivity

“Now it’s quite obvious I can pick it up and if there’s nothing in bold, I know it’s got nothing in that’s wheat; so I’m more open to looking at purchasing PPDS.”

Consumer, England, Severe hypersensitivity

“When it is on the labelling, and right there in front of you it definitely gives you more confidence to go and purchase it.”

Consumer, Northern Ireland, Severe hypersensitivity

However, some consumers did not feel as though they were better equipped to make informed purchasing decisions concerning PPDS food. This was typically because of concerns about the ability of FBOs to control for cross-contamination in food preparation area and the fact that cross-contamination risks were generally not covered on PPDS labels.

“I'm not at all confident and I don't think Natasha's Law has changed that at all. Natasha's Law has changed the way that ingredients are listed, it doesn't talk about cross-contamination or the things that matter to me.”

Consumer, England, Severe hypersensitivity

“The added issue for me is that they could make a sandwich with gluten free bread and with all the right ingredients but could make it on the same chopping board and with the same knife as with a normal sandwich ... The risk of cross-contamination is a very real issue for me. And in my understanding, Natasha's law doesn't cover that.”

Consumer, England, Severe hypersensitivity

Improvement in the ability of consumers to make informed decisions was also mentioned by FBOs and LAs. It was felt that the PPDS labelling requirements had benefitted consumers with food hypersensitivities by providing them with the information they need to decide whether a PPDS food product is safe to eat, without having to ask for assistance.

“I feel that we’ve covered all bases … they can make an informed decision themselves.”

FBO, Scotland, Restaurant/café, 11 or more employees

“I think it is really good for the younger consumer - they may have an embarrassment or concern about asking in front of others - the label can tell them what they need to know.”

Local authority, Northern Ireland

However, PPDS labelling requirements were rarely seen as a perfect solution for those with food hypersensitivities due to the chance of errors being made on labels (particularly amongst smaller businesses with shifting supply chains) and labels not covering the risk of cross contamination. A couple of LAs commented that PPDS labelling requirements may give consumers a false sense of security.

“There might be some aspects in grab and go where it has made a difference to people and (with Natasha) it was a grab and go issue which arose through lack of accurate information rather than lack of any information. If you are an allergen sufferer with potentially very serious reactions, you do not trust anybody to handle food for you.”

Local authority, Scotland

Confidence when purchasing PPDS foods

As with improvements in availability of information, consumers were split as to whether their confidence had increased in buying PPDS foods since the PPDS labelling requirements were introduced. Two-fifths (41%) of consumers reported that they neither agreed nor disagreed, while another two-fifths agreed that their confidence in buying PPDS foods had increased since the PPDS labelling requirements were introduced, with one in twenty (5%) strongly agreeing. Around one in seven (14%) disagreed.

Figure 6.2 Consumer confidence increase in purchasing PPDS foods since the introduction of PPDS labelling requirements

F4. And taking your experience over the last 12 months or so into consideration, to what extent do you agree or disagree that your confidence in buying foods for yourself or your child that are PPDS has increased since October 2021 when the new labelling requirements were brought in? Base: All consumers that buy PPDS foods (1639).

Similar to perceived improvements in the availability of allergen information, there was no difference by country in the proportion of consumers that reported improved confidence (England: 40%, Northern Ireland: 45%, Wales: 37%), but there was in terms of age and frequency of PPDS purchases. Consumers aged between 18 and 34 were more likely than those aged between 35 and 64 and those aged 65 and over to have increased confidence (51% vs 40% and 36% respectively) and so too were those who purchased PPDS foods sometimes or often compared to those who purchased PPDS foods rarely or never (48% vs 36%). Consumers with a regulated allergen were also more likely to report improved confidence compared with those who had a non-regulated allergen only (41% vs 31%).

Changes in purchasing behaviour

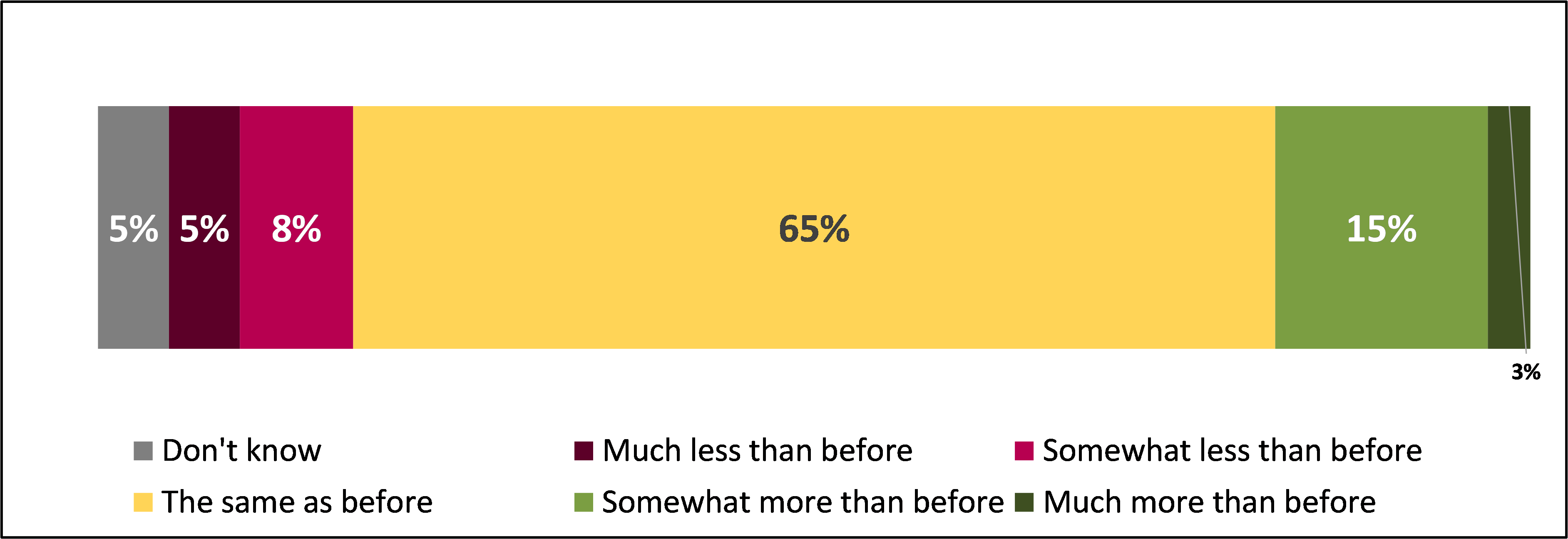

As presented in Figure 6.3, most consumers (65%) reported that their purchasing behaviour had not changed since the introduction of PPDS labelling requirements, with 17% of consumers reporting purchasing more PPDS foods and 14% reporting purchasing less.

Figure 6.3 Consumer PPDS purchasing behaviour since the introduction of PPDS labelling requirements

F3. And since the introduction of PPDS food label requirements, would you say you buy PPDS foods for yourself or your child…? Base: All consumers that buy PPDS foods (1639).

Consumers in England were more likely than those in Northern Ireland to purchase the same amount as before (66% vs 55%), while consumers with a mild or moderate allergy were more likely than those with a severe allergy to purchase the same amount of PPDS foods as before (77% and 69% respectively vs 61%). Older consumers aged between 35 and 64 as well as those aged 65 and over were more likely than those 18 to 34 to buy the same amount of PPDS foods as before (65% and 69% respectively vs 56%). It is worth noting that there were no differences by whether consumers had Coeliac disease or not, whether the respondent or child had a food hypersensitivity and whether the food hypersensitivity was to a regulated or non-regulated allergen.

Six in ten (60%) consumers who considered there to have been an improvement in the availability of ingredients information on PPDS foods (footnote 1) claimed they were purchasing the same amount of PPDS foods as before, while just under a third (31%) reported they were purchasing more PPDS foods since October 2021.

Similarly, whilst around a third (35%) of consumers agreed that their confidence in buying PPDS foods had increased since the introduction of the PPDS labelling requirements (footnote 2) it was more common (58%) that they reported buying the same as before, rather than more than before.

The likelihood of purchasing PPDS foods more often varied by geography and age. Consumers in Northern Ireland were more likely (28%) than those in Wales (21%) and England (16%) to purchase PPDS foods more often since the introduction of PPDS labelling requirements. Younger consumers aged between 18 and 34 were also more likely than those aged between 35 and 64, and those aged 65 and over (26% vs 17% and 12% respectively) to purchase PPDS foods more often.

As illustrated by Figure 6.5, the nature and severity of food hypersensitivities had a bearing over the likelihood to buy PPDS foods more often since the introduction of labelling requirements. Specifically, consumers with severe allergies or intolerances, were more likely than those with mild or moderate allergies or intolerances (19% vs 15% and 14% respectively), and consumers whose child had a food hypersensitivity or both the respondent and their child had a FHS were more likely than those where just the respondent had a FHS (24% and 29% respectively vs 14%). In addition, those with an allergy or intolerance other than Coeliac disease were more likely than those with Coeliac disease (20% vs 15%) to purchase PPDS foods more often than before October 2021. Consumers with allergies/intolerance to regulated allergens were also more likely than those with a non-regulated allergen only (18% vs 9%) to purchase PPDS foods more often.

Figure 6.4 Consumers who purchase more PPDS foods since the introduction of PPDS labelling requirements by nature and severity of hypersensitivity

F3. And since the introduction of PPDS food label requirements, would you say you buy PPDS foods for yourself or your child…? Base: All consumers that buy PPDS foods (1639).

In addition to exploring any effect labelling requirements had on how often consumers purchased PPDS foods, the research also asked about changes to other behaviours (see Figure 6.6). For each of the behaviours asked about, the most common response was that their behaviour hadn’t changed. Six in ten (60%) FHS consumers indicated that they were just as likely to declare their/ their child’s allergy to a provider since the introduction of PPDS labelling. Similar proportions (59%) said that they were just as likely to ask the provider for written information as they were before, 55% to ask for verbal information and 53% were just as likely to rely solely on PPDS labelling as they were before.

However, a smaller group of consumers indicated that their behaviour had changed. A third (34%) said that they were now relying solely on PPDS labelling more than they were, with another third (33%) stating that they were now asking providers for verbal information more than before. Just under a third (31%) said they were now declaring their/their child’s FHS more than they were, and a fifth (20%) said they were now asking providers for written information more than they were.

Figure 6.5 Behaviour changes by consumers in response to the PPDS labelling

E3. Since the introduction of PPDS labelling requirements in October 2021, do you do any of the following more or less than before when purchasing PPDS foods? Base: Consumers that buy PPDS foods (1639).

There were some notable differences by subgroups of consumers, particularly in relation to:

- There were a few differences by country in terms of consumer behaviour changes. Consumers in Northern Ireland were more likely than those in England to declare their or their child’s allergy to food providers more frequently since the introduction of the PPDS labelling requirements (41% vs 30%), and to ask FBOs for verbal information on allergens (47% vs 32%).

- Consumers with severe allergies or intolerances were more likely than those with a mild or moderate allergies to declare their or their child’s allergy to food providers a lot more than before the introduction of the PPDS labelling requirements (23% vs 11% and 19% respectively ), and were more likely to ask FBOs for verbal information more frequently than consumers with mild allergies (36% vs 23%). Consumers with severe allergies were also more likely to ask FBOs for written information more frequently than consumers with mild or moderate allergies (24% vs 11% and 17% respectively).

- Consumers with Coeliac disease were more likely than consumers with a food hypersensitivity other than Coeliac disease to declare their or their child’s allergy more frequently (34% vs 26%), and to ask FBOs for verbal information more often (37% vs 28%).

- Consumers who purchased PPDS foods sometimes or often were more likely than those who purchased PPDS foods rarely or never to rely solely on PPDS labelling more frequently (39% vs 30%).

- There were no significant differences in consumer behaviour changes in terms of consumers with allergies / intolerances to regulated or non-regulated allergens.

Changes in quality of life

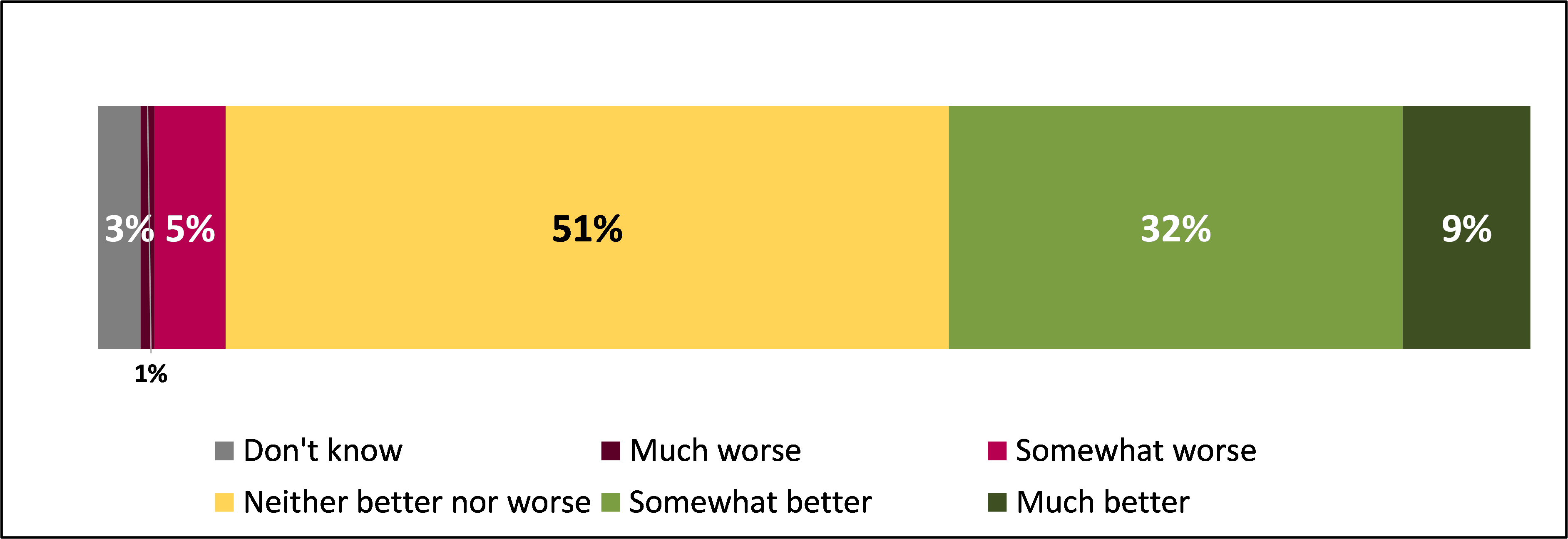

People most commonly reported that their quality of life has stayed the same since the introduction of PPDS labelling: half (51%) said that their quality of life had not changed. However, 40% reported an improvement in their quality of life. As shown in Figure 6.7, 6% of consumers reported their quality of life had worsened to some extent.

Figure 6.6 Change to quality of life due to PPDS labelling requirements

F1. Would you say that the introduction of PPDS food labelling requirements has made your or your child’s quality of life…? Base: All consumers who buy PPDS foods (1639).

There were no significant differences by country in terms of reported improvement in quality of life (England: 39%: Northern Ireland: 49%: Wales: 42%) while consumers in Northern Ireland were less likely than the average to report no change in their quality of life (40% vs 51%).

There were some subgroups of consumers who were more likely to have reported a change in quality of life. These included:

- Consumers with a child or children with a food hypersensitivity were more likely to have noted an improvement in their child’s quality of life than consumers who suffer from a FHS themselves (50% vs 39%), while those who suffer from a FHS themselves were more likely to have reported no change in their quality of life (52% vs 41%).

- Younger consumers aged between 18 and 34 were more likely to report an improvement in their quality of life than those aged 65 and over (47% vs 36%), while consumers aged 65 and over were more likely to report no change in their quality of life than both those aged between 18 and 34 and those aged between 35 and 64 (56% vs 46% and 50% respectively).

- Consumers with an allergy/ intolerance to a regulated allergen were more likely to report an improvement in their quality of life than those with an allergy/ intolerance to a non-regulated allergen only (41% vs 27%).

- Consumers who purchased PPDS foods sometimes or often (48% vs 35%) with consumers who purchased PPDS foods rarely or never being more likely to see no change in their quality of life than those that purchased PPDS foods sometimes or often (55% vs 46%).

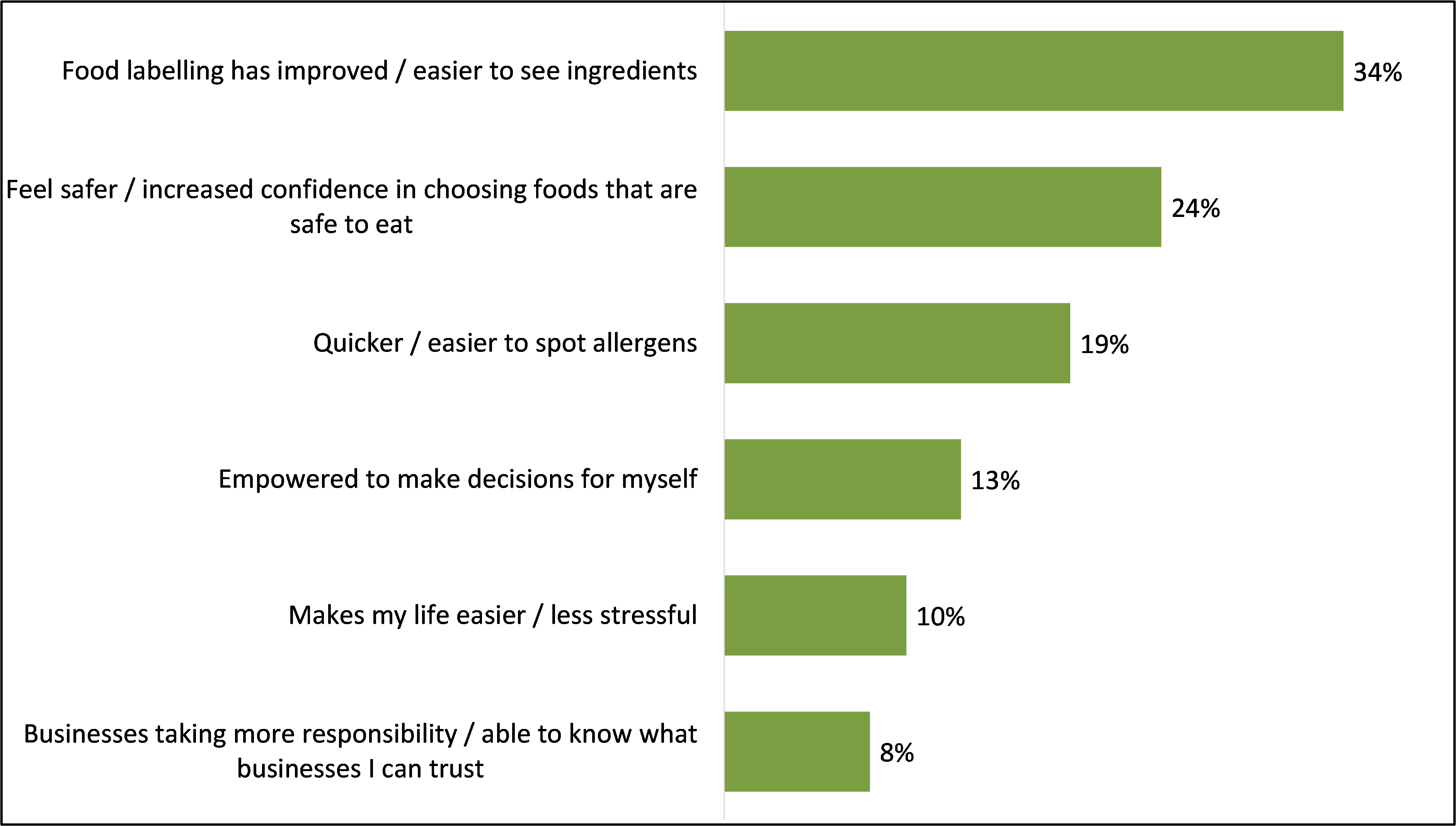

Of those consumers who felt their quality of life had improved (footnote 3), around a third (34%) attributed this to food labelling improvements, just under a quarter (24%) attributed this to feeling safer and more confident in choosing foods that are safe to eat and a just over a fifth (19%) attributed this to it being quicker and easier to identify allergens. All reasons given for quality-of-life improvements are presented in Figure 6.8.

Figure 6.7 Reasons for improvements in quality of life in consumers with food hypersensitivities

F2. In what ways would you say the introduction of prepacked for direct sale (PPDS) food labels requirements made your / your child’s quality of life? Base: Consumers who have noticed an impact of PPDS labelling requirements on their quality of life (801). NB: responses under 6% have not been displayed.

Consumers who felt their quality of life had gotten worse (footnote 4) also gave reasons for this change, with the most common reason that they found their choices more limited (57%), that they required clarification on inconclusive or contradictory labelling (45%), and that staff still lacked knowledge on allergen information (28%).

Reflecting the survey findings, during qualitative interviews, many consumers spoke about how the labelling requirements have made a difference to their quality of life in terms of enhanced convenience and being able to make purchasing decisions more quickly.

"It makes such a difference to when I was first diagnosed (in 2000). Just giving up gluten, my first supermarket shop took 5 hours because there was no allergy labelling so you had to read every single ingredient and interpret that ingredient, because not everything was called wheat or gluten."

Consumer, England, Moderate hypersensitivity

“New labelling requirements have made it quicker to identify whether I can buy that product or not by checking the bold writing.”

Consumer, England, Severe hypersensitivity

Observed changes in FBO behaviour

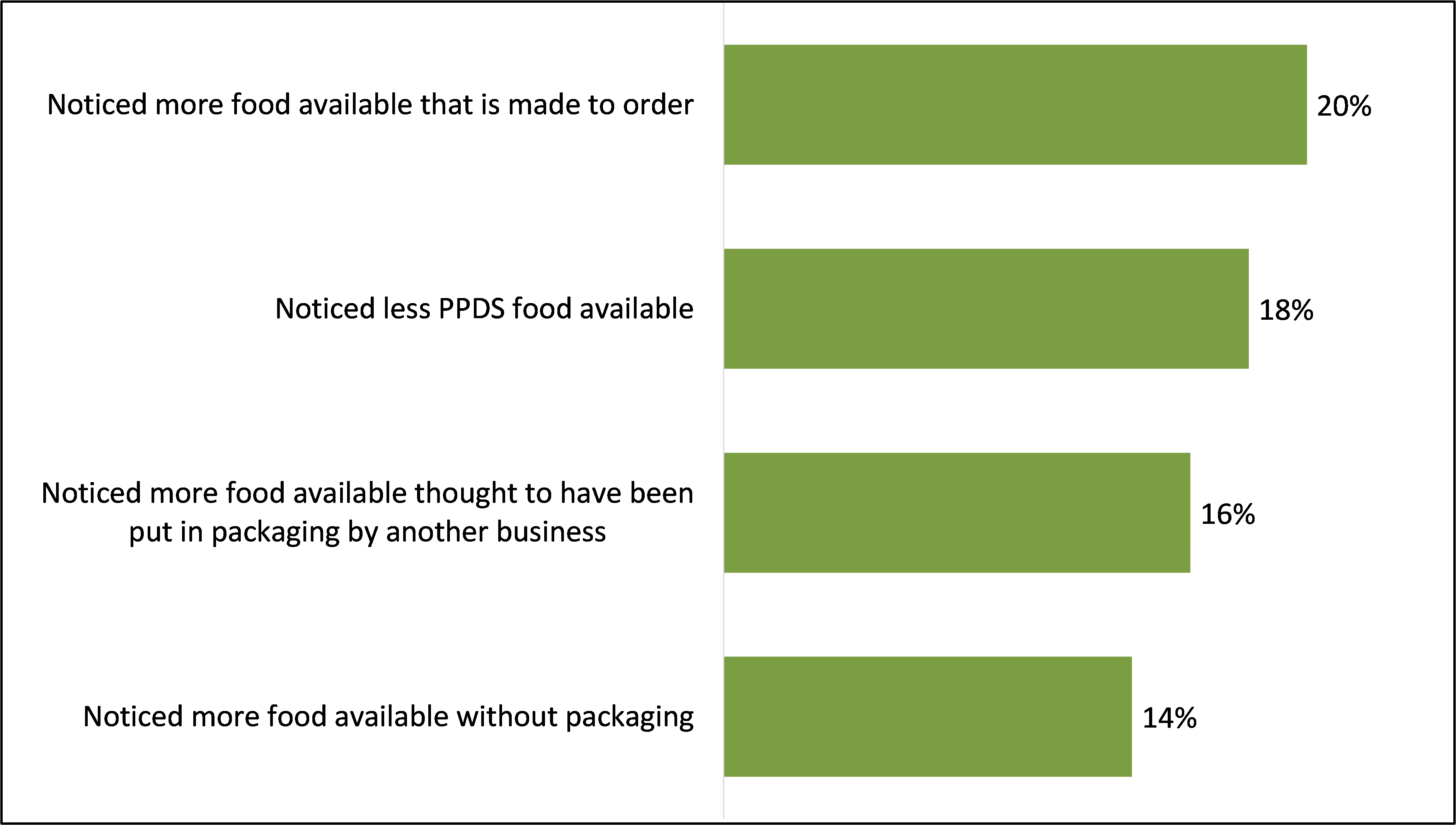

Most consumers (60%) had not noticed any changes in FBO behaviour since the PPDS labelling requirements were introduced. Where changes had been observed, the most common were an increase in the availability of food made to order (20%) and a reduction in the availability of PPDS foods (18%). Some consumers had observed food that was previously sold as PPDS being packaged differently, 16% noting an increase in prepacked food and 14% noting an increase in non-prepacked food.

Figure 6.8 FBO behaviour changes noticed by consumers

E10. Since the introduction of PPDS food labelling requirements in October 2021, have you noticed any of the following changes? Base: Consumers that buy PPDS foods (1639).

There were differences among subgroups for consumers who have noticed business behaviour changes:

- Consumers in Wales were more likely to notice more food being available to order than those in England (26% vs 19%), as well as those with a non-regulated allergen only, who were more likely than those with a regulated allergen to notice this behaviour (29% vs 18%). Consumers with a FHS other than Coeliac disease were more likely than those with Coeliac disease to notice this behaviour (26% vs 15%), as well as those that buy PPDS foods often or sometimes, who were more likely than those that buy PPDS foods rarely or never (24% vs 17%). Finally, younger consumers aged between 18 and 34 were more likely than those aged between 35 and 64 and those aged 65 and over to report this behaviour change (26% vs 19% and 19% respectively).

- Consumers that buy PPDS food often or sometimes were again more likely to report noticing less PPDS foods available than those who buy PPDS foods rarely or never (20% vs 17%). Younger consumers aged between 18 and 34 were more likely than those aged between 35 and 64 to notice this change (22% vs 16%).

- Younger consumers aged between 18 and 34 were more likely than those aged between 35 and 64 and those aged 65 and over to report noticing more foods thought to have been put in packaging by another business (27% vs 15% and 12% respectively).

- Consumers in Wales were more likely to notice more food available without packaging than those in England (20% vs 13%), as well as those with a non-regulated allergen only, who were more likely than those with a regulated allergen (20% vs 12%). Consumers with a FHS other than Coeliac disease were more likely than those with Coeliac disease to notice this behaviour change (18% vs 10%).

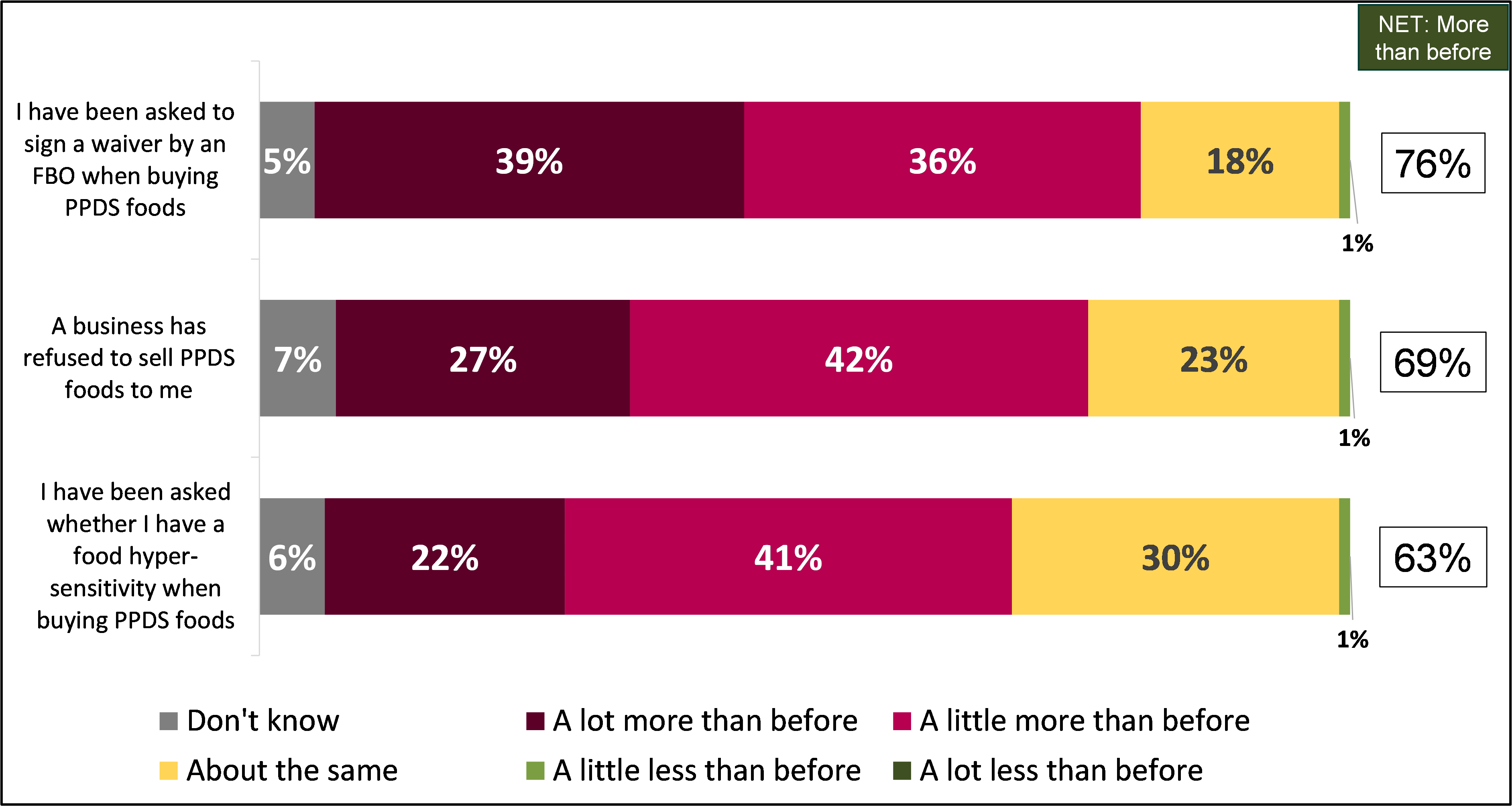

Business behaviours experienced by consumers

One tenth (10%) of consumers who buy PPDS foods reported being asked to sign a waiver by an FBO when buying PPDS foods. Under one fifth of consumers who buy PPDS foods (18%) reported being asked whether they had a food hypersensitivity by FBOs, and under one fifth (16%) of consumers who purchase PPDS reported experiencing FBOs refusing to sell to them.

These behaviours were also reported by FBOs who sell PPDS foods and were aware of the PPDS requirements, with one tenth (9%) reporting asking consumers to sign a waiver when selling PPDS foods, just under two fifths (39%) reported asking consumers whether they had a FHS, and under one tenth (8%) have refused to sell PPDS foods to consumers with FHS.

However, for most consumers who had experienced these behaviours, they had done so more since the introduction of the new labelling requirements than before. As shown in Figure 6.9, over three-quarters (76%) of consumers who had been asked to sign a waiver had experienced that more than before the introduction of PPDS labelling requirements. (footnote 5) Just over two-thirds (69%) of those who had been refused service of PPDS foods had experienced that more, and just under a third (63%) of those who had been asked whether they had a food hypersensitivity when buying PPDS foods had experienced that more. (footnote 6)

Figure 6.9 Changes in frequencies of business behaviours by consumers who have experienced them since October 2021

E12. And would you say you’ve experienced the following more, the same or less than before the introduction of PPDS labelling requirements in October 2021? Base: Consumers that experienced each behaviour in E11: being asked by a food business to sign a waiver relating to my or my child’s food hypersensitivity when buying PPDS foods (170), Being asked about whether I have or my child has a food hypersensitivity when buying PPDS foods (298), Being denied service or a business refusing to sell PPDS foods to me or for my child (257).

Younger consumers aged between 18 and 34 who had prior experience of FBOs asking whether they had a food hypersensitivity were more likely than those aged 65 and over (75% vs 51%) to report an increase in the frequency of this business behaviour since October 2021.

Consumers that had previously been refused service in FBOs in England were more likely than average (72% vs 69%) to have reported an increase in the frequency of this behaviour. Consumers with severe allergies were more likely to have reported that this behaviour had happened about the same as before than those with moderate allergies (27% vs 13%).

Food Business Operators

There was evidence of the PPDS labelling requirements having some negative effects on FBOs, particularly in terms of operating costs and administrative burden. However, for other FBOs the impact was more minimal, for example, for just under two fifths (37%) of FBOs there were no changes in terms of operating costs. There was also evidence that the implementation of PPDS labelling requirements had affected the types of food some FBOs sold and their approach to serving FHS consumers.

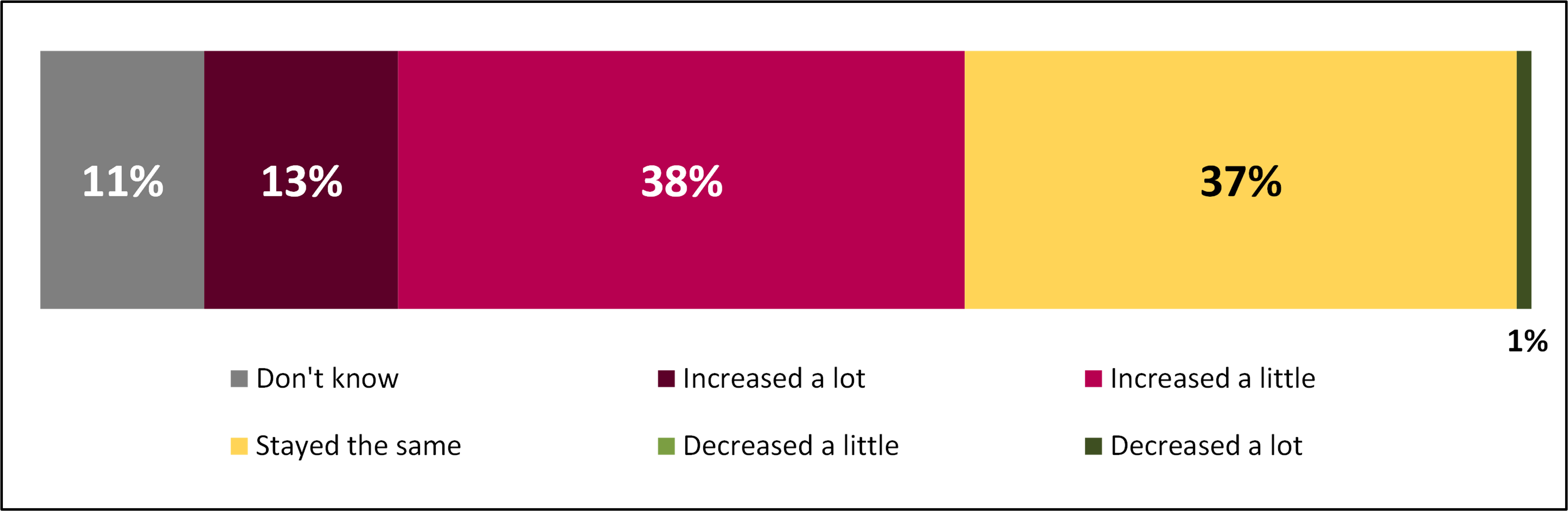

Impacts on FBO costs

Half (51%) of FBOs that sell PPDS foods and were aware of PPDS labelling requirements said their costs had increased because of the PPDS labelling requirements. For these FBOs, costs had tended to increase by ‘a little’ (38%) rather than ‘a lot’ (13%). Under two fifths (37%) of these FBOs reported their costs had stayed the same, while just 1% noted a decrease, as set out in Figure 6.10.

Figure 6.10 Extent to which costs increased due to the PPDS labelling

C3. To what extent, if at all, have the costs of the business changed because of any of the PPDS labelling requirements? Base: FBOs that sell PPDS and were aware of PPDS labelling requirements (766).

The proportion of FBOs that reported increased costs was broadly consistent across all four countries (England: 51%, Northern Ireland: 44%, Scotland: 52%, and Wales: 55%) and number of employees (1 to 5 employees: 54%, 6 to 10 employees: 48%, 11 or more employees: 48%). There was little variation by sector. However, catering FBOs (59%) and butchers (58%) were more likely than general retail businesses (45%) to report increased costs.

The most common reason given for increased costs was investment in equipment or materials (55%), followed by time spent preparing and applying labels to PPDS foods (36%), and time spent checking or updating labels (27%). Causes of increased costs are shown in Figure 6.11.

Figure 6.11 Reasons for increase in costs due to the PPDS labelling requirements

C4. What has caused costs to increase? Base: FBOs that have seen increased costs due to PPDS labelling requirements (394). NB: responses under 6% have not been displayed.

Investment in equipment or materials was the most common reason given for increased costs, more likely for mid-size FBOs, with those with between 6 and 10 employees more likely than FBOs with between 1 and 5 and 11 or more (67% vs 51% and 53% respectively). Furthermore, catering sites were more likely than retail sites to have incurred additional costs through time spent preparing and applying labels to PPDS foods (41% vs 31%) as well as FBOs with between 6 and 10 employees who were more likely than FBOs with 11 or more employees (41% vs 27%).

During qualitative interviews, most FBOs that had experienced an increase in costs explained that the most significant cost was the initial outlay on hardware and software. Many continued to face higher costs (e.g. the cost of materials and staff time to prepare and check labels of packaging) following this initial investment, but these were less significant that the set-up costs and did not pose an issue to the survival of the business.

“It cost nearly £2,000 for equipment … the time taken to label has reduced to nearly pre-PPDS levels, however the cost of labels is more expensive now as they're bigger. We have not increased prices charged to customers as a result.”

FBO, England, Caterer, 6 to 10 employees

“The cost implication has changed, because we now have to print two labels.”

FBO, England, Caterer, 1 to 5 employees

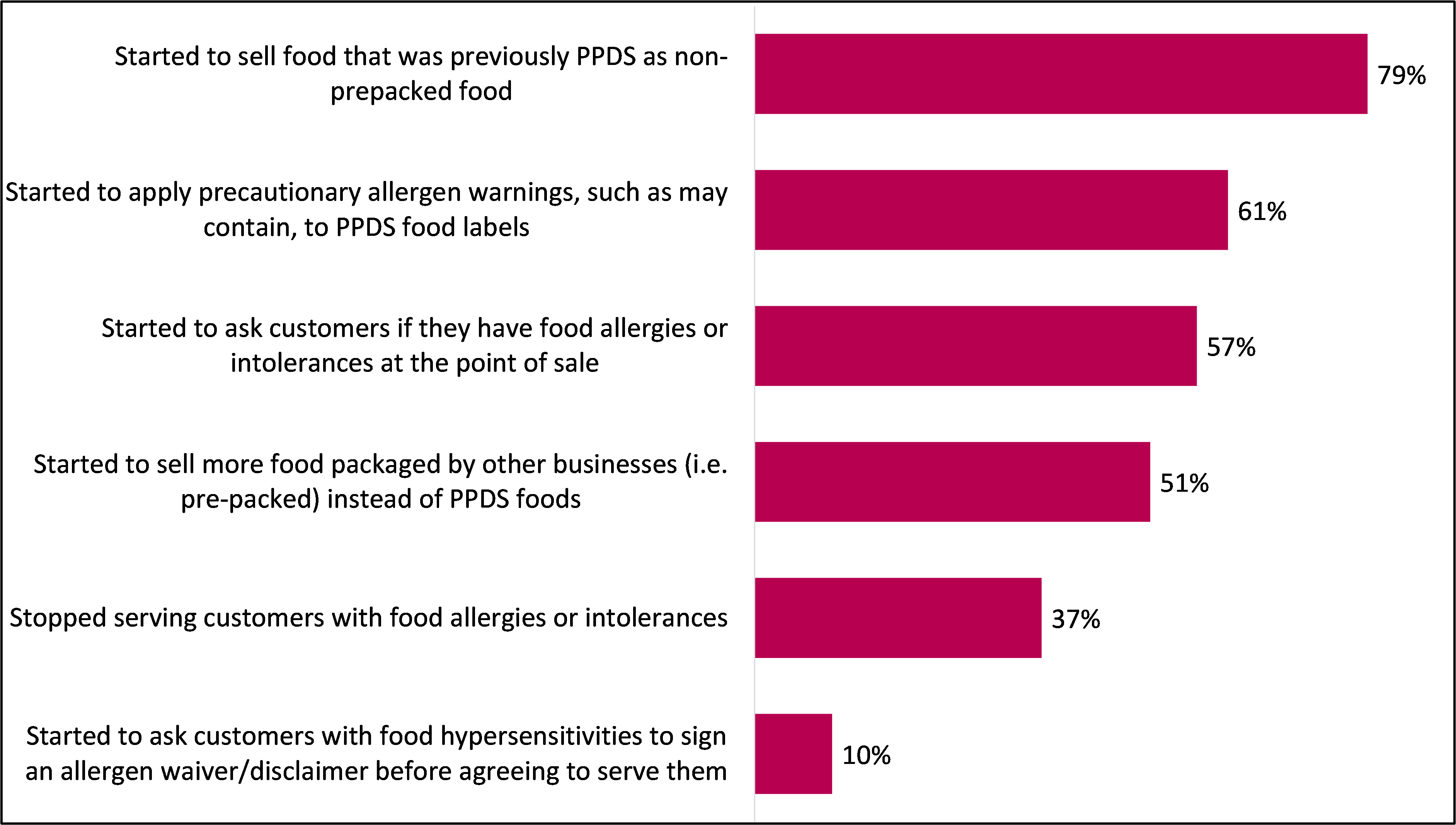

Changes to business practices

Most FBOs (79%) that sold PPDS foods and were aware of the PPDS labelling requirements had made some changes to their business practices since October 2021. (footnote 7) The most common change was starting to apply Precautionary Allergen Labelling (PAL) to PPDS foods (58%), followed by starting to ask customers if they had food allergies or intolerances at the point of sale (39%). More than a fifth (22%) of businesses changed the foods they sell, with 17% selling food that was previously PPDS as non-prepacked food, and 15% starting to sell more food packaged by other businesses. Changes in business practice are shown in Figure 6.12 below.

Figure 6.12 Self-reported changes in business practices since the introduction of PPDS labelling requirements

C5. Has the introduction of PPDS labelling requirements caused the business to do any of the following…? Base: FBOs that sell PPDS and were aware of PPDS labelling requirements (766).

There were only minor differences in changes made by country, sector and size.

- FBOs in England were more likely (59%) to have started to add PAL to their PPDS foods than FBOs in other countries (Northern Ireland 41%, Scotland 54%, and Wales 53%).

- General retail sites were more likely (24%) than bakers (8%), butchers (11%), and restaurants and cafés (11%) to have started to sell more foods packaged by other businesses.

- Restaurants and cafés were more likely than catering FBOs to ask customers to with food allergies or intolerances to sign an allergen waiver or disclaimer before agreeing to serve them (13% vs 5%).

- FBOs in England were more likely than those in Scotland to ask consumers if they had a food hypersensitivity at the point of sale (40% vs 31%). Catering FBOs were also more likely than retail FBOs to display this behaviour (51% vs 28%), underlined by catering businesses and restaurants and cafés (50% and 52% respectively). Smaller FBOs with between 1 and 5 employees were also more likely than those with between 6 and 10 and those with 11 or more to display this behaviour (47% vs 34% and 30% respectively).

During qualitative interviews, FBOs that had started to sell more prepacked and non-prepacked foods since the introduction of PPDS labelling requirements explained that the reason for this was to remove certain products from falling within the PPDS labelling requirements. The justification behind this was that the business would be unable to take on the additional administration and costs of packaging and labelling all PPDS products.

“We buy lower quality ones in from a supplier now. PPDS was the main reason because there is now much more labelling and packaging to do.”

FBO, England, Caterer, 11 or more employees

Of the FBOs that had started to sell more non-prepacked foods (48%, n=133), 17% reported that this change had little or no impact on the business, while of the FBOs that have started to sell more prepacked foods (15%, n=111), 22% reported that this change had little or no impact on the business. Where these changes did have reported impacts, the most common mentioned by those that had started to sell food that was previously PPDS as non-prepacked foods was higher pressure on the business (13%), and increased consumer confidence or satisfaction (10%).

Amongst those that started to sell more prepacked food, the most common impact was increased costs or decreased sales (21%).

Almost all Local Authorities (LAs) (97%) had observed FBOs making changes to their practices since the introduction of PPDS labelling requirements. As presented in Figure 6.13, the most common change LAs had observed was FBOs starting to sell food that was previously PPDS as non-prepacked food (79%), followed by FBOs starting to apply PAL warnings to PPDS food labels (61%) and FBOs starting to ask customers if they had food allergies or intolerances at the point of sale (57%).

Figure 6.13 Self-reported and LA observed changes in business practices since the introduction of PPDS labelling requirements

FBO survey, F1. Since the introduction of PPDS food labelling requirements in October 2021, have you observed businesses doing any of the following? Base: All LAs (126).

Compared with FBO self-reported changes to their business practices (see Figure 6.12), LAs were much more likely to have observed FBOs starting to sell food that was previously PPDS as non-prepacked food (79% LAs vs 17% FBOs), FBOs starting to sell more food packaged by other businesses instead of PPDS foods (51% LAs vs 15% FBOs) and FBOs stopping serving customers with food hypersensitivities (37% LAs vs 8% FBOs), shown in Figure 6.13. These differences may have been caused by a self-report bias amongst FBOs, as well as the fact that they are reporting on a larger sample and may be more likely to find incidence. However, the differences regarding the types of food products sold, may also stem from issues with FBO comprehension of the definition of different categories of food (e.g. PPDS, prepacked and non-prepacked).

Reasons FBOs have stopped selling PPDS foods

Amongst the FBOs that had stopped selling PPDS foods after October 2021, a fifth (21%) attributed this to the PPDS labelling requirements. (footnote 8) More common reasons were changes to consumer preferences or the food not selling well (32%) and resource pressures (e.g. time, money, or space; 26%). Amongst those that attributed stopping the sale of PPDS foods to the labelling requirements (n=12), three said this was due to time taken to introduce and update labelling for PPDS foods . Reasons for stopping selling PPDS foods mentioned are shown in Figure 6.14 below.

Figure 6.14 Factors which played a part in FBOs decision to stop selling PPDS

D2. What factors played a part in the decision to stop selling PPDS foods? Base: FBOs that previously sold PPDS foods but have stopped (62).

Local Authorities

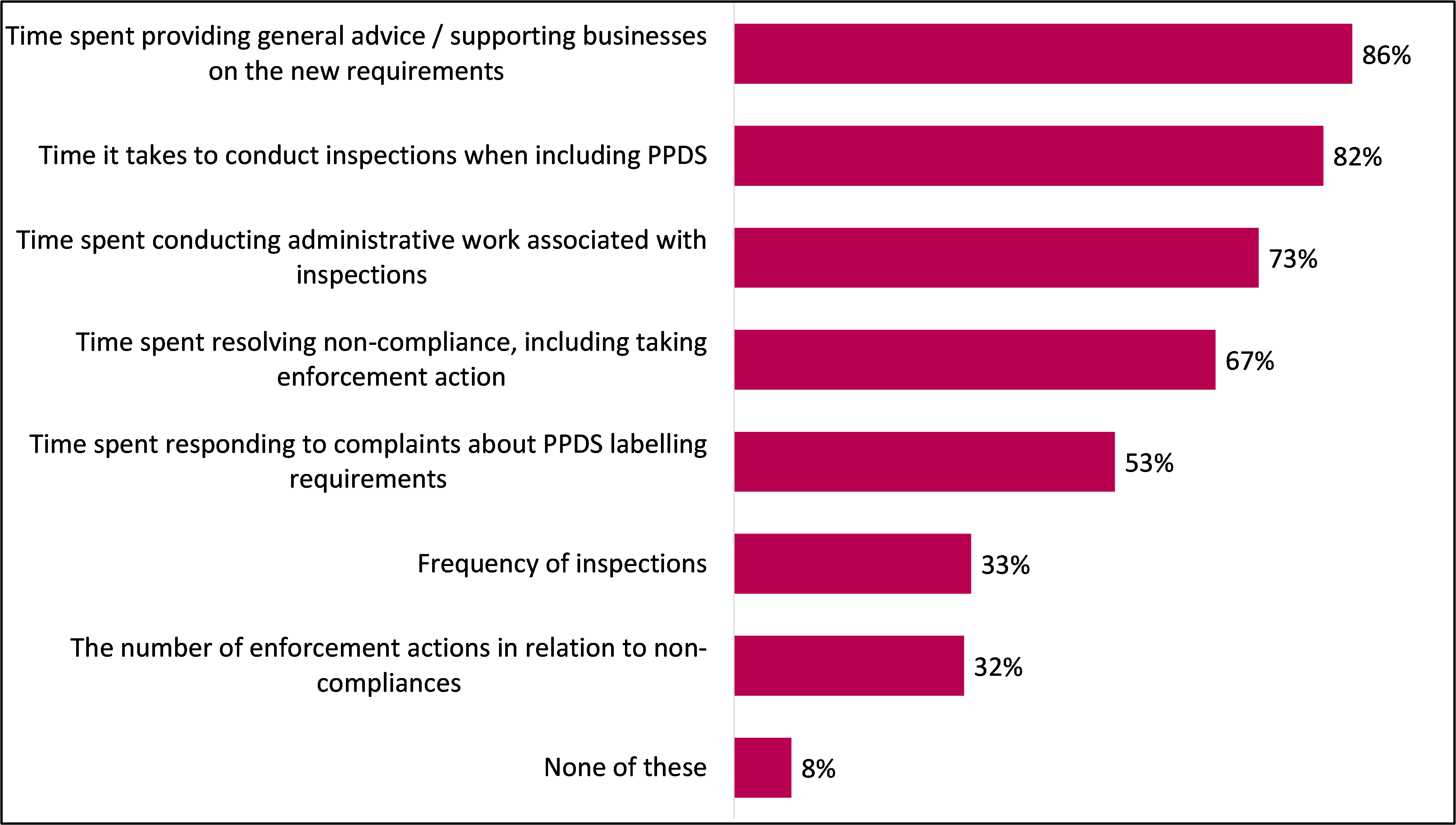

Most LAs (92%) reported an increase in at least one aspect of their work because of the introduction of PPDS labelling requirements. The most common increase reported related to the time spent providing advice and support to businesses (86%). A majority of LAs also cited an increase in both the time to conduct the inspections themselves (82%), the associated administrative work relating to inspections (73%) and time spent resolving non-compliance and taking enforcement/follow-up actions (67%).

Figure 6.15 Extent to which certain areas of LA responsibility have increased as a result of the introduction of PPDS labelling requirements

E1. To what extent have the following increased or decreased as a result of the introduction of PPDS labelling requirements on 1 October 2021? Base: All LAs (126).

As presented in Table 6.1, amongst those that reported an increase in time spent conducting inspections, conducting administrative work associated with inspections and conducting enforcement/follow up action, LAs typically estimated that time had increased by less than 30 minutes per inspection.

Table 6.1 : Extra time spent by LAs on inspections and the associated administrative work

| Time increase | Extra time per inspection spent inspecting food businesses due to the introduction of PPDS labelling requirements | Extra time per inspection spent on administrative work | Extra time per inspection spent conducting enforcement/follow up action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Less than 15 minutes | 26% | 34% | 14% |

| Between 15 and 30 minutes | 53% | 43% | 25% |

| Between 30 and 45 minutes | 11% | 9% | 13% |

| Between 45 and 60 minutes | 4% | 4% | 0% |

E2. How much extra time per inspection has been spent inspecting food businesses due to the introduction of PPDS labelling requirements? Base: LAs who have spent more time on inspections due to PPDS labelling requirements (103). E3. How much extra time per inspection has been spent on administrative work (e.g. inputting on data systems, writing advice emails and letters) associated with inspections since the introduction of PPDS labelling requirements? Base: LAs who have spent more time on administrative work associated with inspections due to PPDS labelling requirements (92). E4. Roughly, how much extra time per inspection has been spent conducting enforcement/follow up action with food businesses found not to be compliant with PPDS labelling requirements? Base: LAs who have spent more time on enforcement (84).

During the qualitative interviews many LAs spoke about how the increase in time spent conducting inspections and administrative work associated with inspections was borne out of a lack of capacity to undertake the additional checks, paperwork and re-visits.

“There is more involvement with the businesses; more time spent so providing information, going over information and the follow up in writing after a visit … admin increased quite a bit with regards to follow ups and information provided … we have other duties but food takes priority so things like health and safety slides to the bottom a wee bit.”

Local Authority, Scotland

During the qualitative interviews, LAs explained that the additional time spent on enforcement/follow-up actions had typically been spent on signposting to and delivering advice and guidance. As detailed in Chapter 5, many LAs explained that their focus for the first year of the PPDS labelling requirements being in effect had been to educate FBOs and support them with compliance rather than pursue enforcement. Only a few LAs reported taking formal enforcement action. For example, in instances where FBOs did not need their advice or were found to still be non-compliant at the point of re-visit.

“I can’t see us rushing to prosecute on this. If I advise them to take it off sale, then that’s avoided me going through a whole lot of forms and bureaucracy just to get the same result.”

Local Authority, Wales

Figure 6.16 Case study: Effects of PPDS labelling requirements (accessible version)

An English Local Authority reported an increase in the amount of time spent conducting inspections, completing administrative work associated with inspections and resolving non-compliance since the PPDS labelling requirements were introduced.

The increased time spent on these tasks was attributed to a variety of factors, including more paperwork for officers to complete, an increase in the volume of samples collected during inspections and a high rate of non-compliance amongst FBOs in the area. It was estimated that there have been an additional 27 enforcement actions since 1 October 2021 compared the previous year.

“We've increased the amount of samples that we take, and I think it was unexpected that we would find such a high level of non- compliance.”

The Local Authority explained that many FBOs had taken steps to avoid the PPDS labelling requirements by packaging products differently. For example, selling sandwiches in an unsealed bag.

“Businesses are generally doing everything they can to avoid being caught, so they are making up to order and just sticking it loose in a paper bag.”

A farm shop, located in the same Local Authority with 11 or more employees.

The operating costs of this FBO have increased since the introduction of PPDS labelling requirements. This was attributed to the need to invest in new processes and dedicating labour to labelling and packaging. The FBO has responded by increasing their prices.

“It is manual labour so making sure we have processes in place, and physical labelling and packaging, it adds up very quickly … Generally we are passing it on to the consumer because we have higher prices.”

The FBO still sells PPDS food, but in an attempt to reduced administrative burden and increases costs they had also started to sell some foods that were previously PPDS as loose foods.

“The steps we took were to put products behind the counter and every counter or display where we have loose products, we have signage that says ask a member of the team for allergens … and baked products so biscuits, tarts and quiches.”

-

42% of consumers that buy PPDS foods feel the availability of the information needed to identify a food that may cause an unpleasant reaction (n=683).

-

40% of consumers that buy PPDS foods agreed that their confidence in purchasing PPDS foods had increased since the introduction of the PPDS labelling requirements (n=660)

-

40% of consumers who buy PPDS foods reported an improvement in their quality of life (n=659)

-

6% of consumers that buy PPDS foods reported their quality of life had gotten worse since the introduction of PPDS labelling requirements (n=102).

-

10% of consumers that buy PPDS food had been asked to sign a waiver relating to their food hypersensitivity when buying PPDS foods since October 2021 (n=170).

-

16% of consumers that buy PPDS food had been refused service of PPDS foods since October 2021 (n=257). 18% of consumers that buy PPDS food had been asked whether they had a food hypersensitivity when buying PPDS since October 2021 (n=298).

-

83% of all FBOs sold PPDS foods and were aware of the PPDS labelling requirements (n=766).

-

8% of FBOs reported that they stopped selling PPDS food since October 2021 (n=62).