Evaluation of the implementation of prepacked for direct sale (PPDS) allergen labelling requirements

An evaluation of the implementation and effect of the updated prepacked for direct sale (PPDS) allergen labelling requirements.

Introduction

The Food Standards Agency (FSA) and Food Standards Scotland (FSS) play an important role in ensuring members of the public with food hypersensitivities are protected from potentially life-threatening reactions. They work with the food industry to ensure that food labelling allows consumers with food hypersensitivities to make informed, safe choices.

In December 2014, food labelling and allergen information requirements were updated. Food Business Operators (FBOs) were then required to provide allergen information for non-prepacked foods, including those prepacked for direct sale (PPDS). PPDS foods are those that are packed before being offered for sale by the same food business on the same premises or location (or from moveable or temporary premises). The law at this time allowed for allergen information for these foods to be communicated in writing or verbally.

In 2016, Natasha Ednan-Laperouse died from an allergic reaction to a baguette which was PPDS. Following this, there was a campaign for the expansion of legislation to bring the labelling requirements of PPDS foods more in line with prepacked foods. Under this legislation, often known as ‘Natasha’s Law’, it has been a legal requirement since 1 October 2021 for PPDS food labels to clearly display the name of the food and a full ingredients list with the 14 regulated allergens emphasised within the list.

One year after it became a legal requirement across the United Kingdom (UK), the FSA and FSS wanted to evaluate its implementation and the effect it has had on three key groups: Food Business Operators (FBOs), Local Authorities (LAs) and consumers with food hypersensitivities (FHS).

This evaluation aimed to understand:

- Awareness of the new requirements across FHS consumers, FBOs and LAs

- Uptake and compliance with the new requirements

- The effect of PPDS legislation

- LA experience of supporting compliance

- Success factors and lessons learned from the implementation of PPDS legislation and how this could be applied in future.

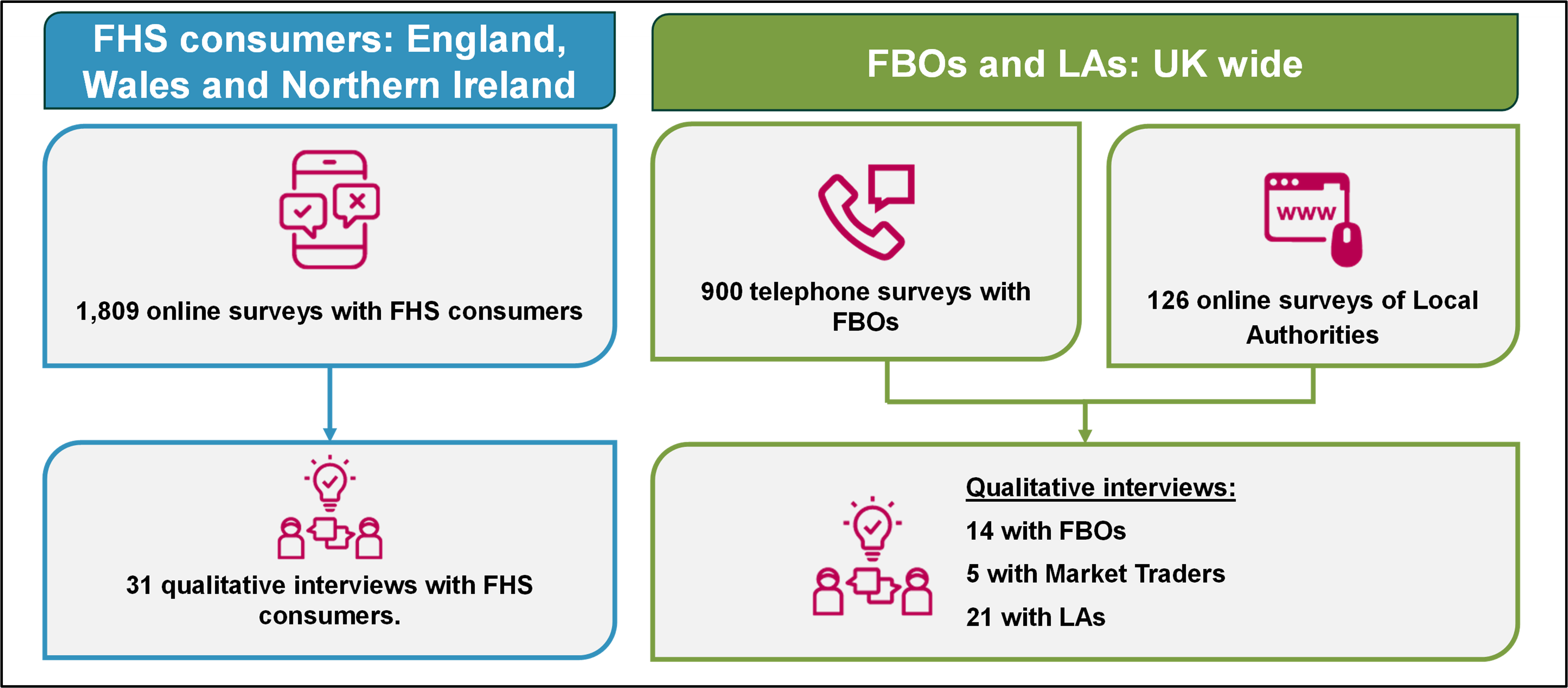

IFF Research were commissioned to conduct this evaluation on behalf of the FSA and FSS, taking a mixed-method approach. A quantitative survey was conducted with each of the key audiences followed by qualitative interviews between November 2022 and February 2023: (footnote 1)

- Consumer research: A total of 1,809 consumers who either had a food hypersensitivity themselves (n=1,610) or had a child with a food hypersensitivity (n=199), most of whom (92%) had an allergy to at least one of the 14 regulated allergens, took part in an online survey. This included consumers residing in England (n=1,539), Northern Ireland (n=102) and Wales (n=168), consumers in Scotland were not included in the research as FSS are conducting their own research which will be published separately. A total of 31 consumers also participated in a follow-up qualitative interview.

- FBO research: 900 FBOs across the UK took part in a telephone survey, this included FBOs in England (n=612), Northern Ireland (n=52), Scotland (n=161) and Wales (n=75). A total of 19 completed a follow-up qualitative interview, 5 of whom were market traders.

- LA research: All 398 LAs across the UK were contacted to take part in an online survey, with 126 completes across 124 different LAs, (footnote 2) in England (n=85), Northern Ireland (n=11), Scotland (n=20) and Wales (n=10). A total of 21 LAs also took part in a follow-up qualitative interview.

Awareness and understanding of PPDS labelling requirements

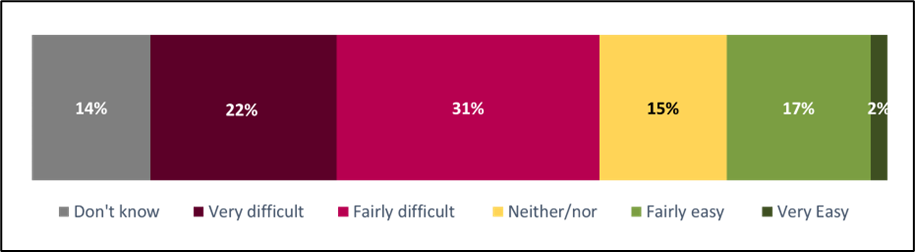

Awareness of the term PPDS was fairly low among consumers with a food hypersensitivity (26%). Once defined to consumers as: ‘Pre-packed for direct sale (PPDS) foods are packed on the same premises as they are being sold to consumers and where the food is packed before being offered for sale to customers’, around half of consumers (52%) reported it would be difficult for them to identify whether food was PPDS or not.

Awareness among consumers of the new PPDS labelling requirements was higher than the term PPDS itself, with the vast majority (87%) stating they had heard of it, though only a smaller proportion had detailed knowledge of it (18% stated that they knew quite a lot about it, 40% said they knew a bit about it and 24% did not know much about it). Awareness being much higher for the labelling requirements, compared to the definition of PPDS foods, could be due to the media coverage of Natasha Ednan-Laperouse’s death, this was cited by most consumers in the qualitative interviews.

With regards to knowledge of specifics of PPDS labelling requirements; around eight in ten (78%) consumers believed that FBOs were legally required to provide a full written ingredients list on PPDS foods. Consumers shared whether, in their view, PPDS foods only needed to be labelled with information about whether they contain any of the 14 specified allergens, rather than with a full ingredients list; only a fifth (21%) agreed with two thirds (67%) disagreeing, indicating a preference for a full ingredients list.

Around two-thirds (66%) of FBOs were aware of the term ‘prepacked for direct sale’ (PPDS) before participating in the research, though once shown the definition most (over 80%) were clear on the various aspects of the PPDS definition. These aspects included:

- What the definition of packaging is (94% clear)

- When food is placed into packaging (92% clear)

- Whether how accessible an item of food is to consumers matters (91% clear)

- Which foods meet the definition of PPDS (91% clear)

- Where packaging needs to take place for an item to count as PPDS (90% clear)

- Which premises constitute part of the same food business (82% clear)

In addition, the vast majority of FBOs (91%) were aware of the PPDS labelling requirements, specifically that on 1 October 2021 it became a legal requirement to label PPDS foods with the name of the food and a full ingredients list, with allergenic ingredients emphasised within the list. High levels of awareness were also demonstrated throughout the qualitative interviews, though some FBOs did explain that they faced a steep learning curve initially, due to having previously not used the term PPDS. From a LA perspective, they also tended to believe that FBOs had good awareness and understanding of requirements.

LAs were also asked, like FBOs, if they were clear on each of the aspects of the PPDS definition mentioned above, with 57% clear on all aspects, and over 80% clear on each individual aspect. Qualitative interviews showed that LAs who took part in the research had a high level of understanding of the labelling requirements, though there were pockets of confusion and uncertainty around specific foods and packaging. A key example of this confusion included specific foods at takeaway premises that are made in bulk then prepacked ahead of an order and bundled later with an order of non-prepacked food, such as prawn crackers and condiments.

Experience of PPDS labelling requirements

Consumer purchasing behaviour, experience, and confidence in PPDS labelling

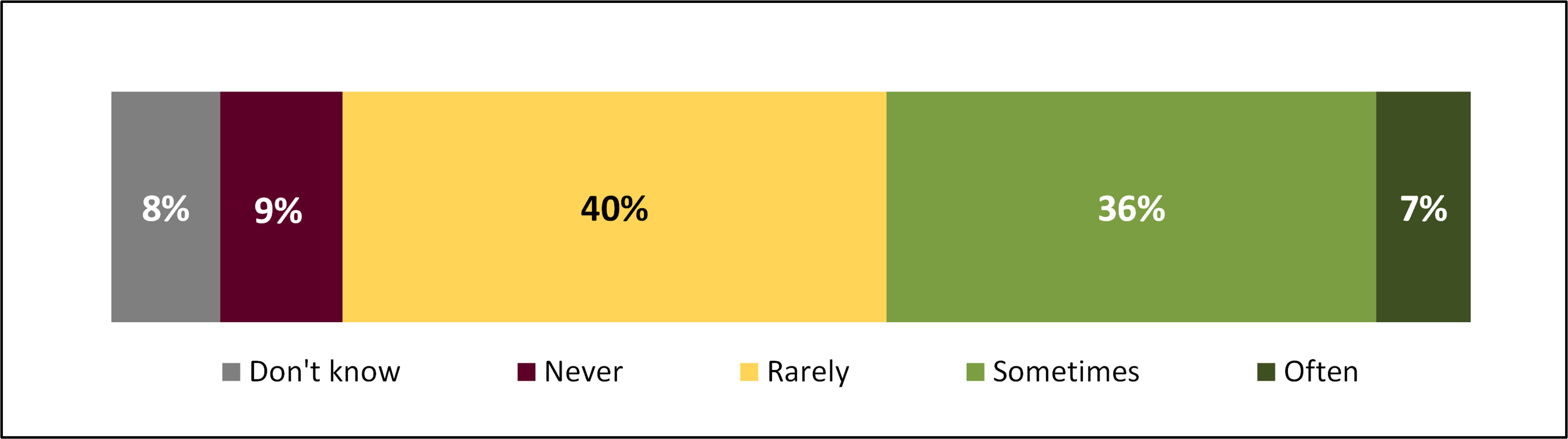

It was uncommon for FHS consumers to purchase PPDS foods often (7%). Instead, most consumers reported buying PPDS foods sometimes (36%) or rarely (40%). The nature of consumer’s food hypersensitivities tended to contribute to their likelihood to purchase PPDS foods. Those with allergies and intolerances other than Coeliac disease were more likely to do so than those with Coeliac disease (92% vs 89%) and those with a mild (97%) or moderate (96%) allergy or intolerance were more likely to purchase PPDS foods that those with a severe allergy or intolerance (87%). For a number of consumers in the qualitative interviews, concerns over allergen cross-contamination meant they were unlikely to purchase PPDS foods or to only do so as a last resort.

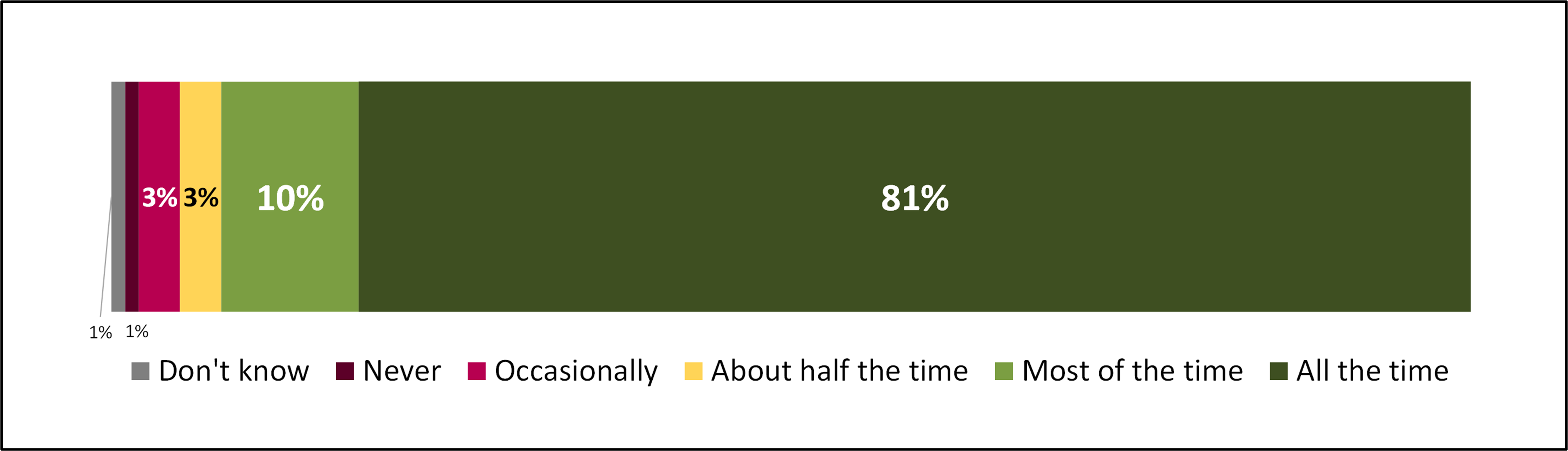

More than nine in ten consumers surveyed purchased PPDS foods (91%). Of these, four fifths (81%) reported checking labels on such products every time a purchase was made and a further 10% reported doing so most of the time. Ease of identifying PPDS foods may contribute to this figure, given half of consumers find it difficult to identify PPDS foods. Consumers who found it difficult were more likely to check the labels more often (95% always or most of the time vs 88% of those who find it easy).

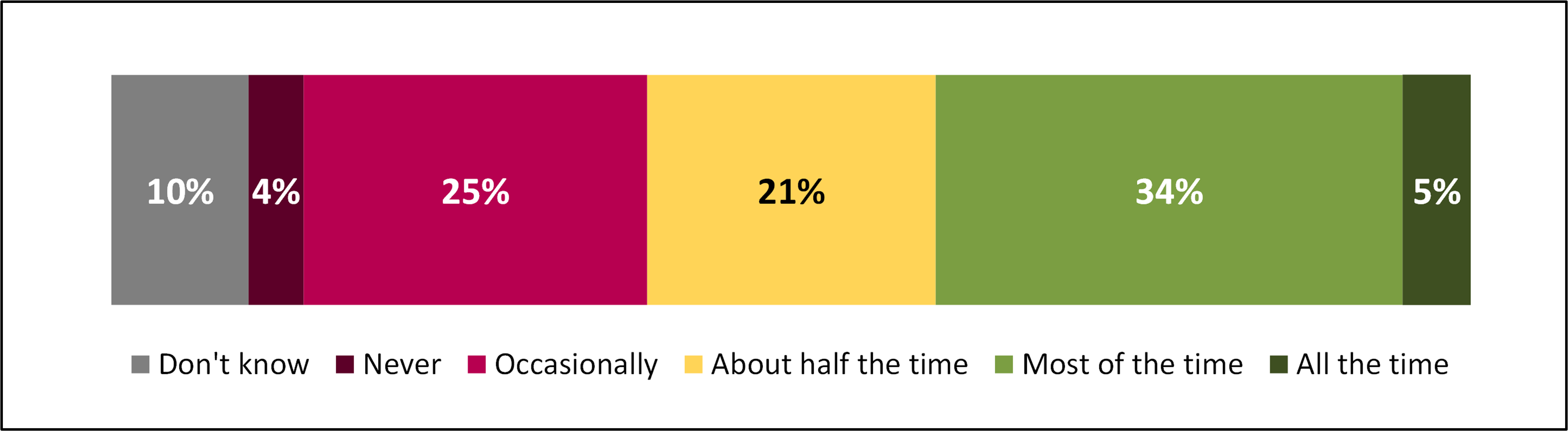

Amongst those that checked the labels of PPDS foods, only one in twenty (5%) reported that they were always able to access the information they needed to be able to identify whether it contains an ingredient that would cause an unpleasant reaction. Of the remainder, a third (34%) said that the information they required was available most of the time, a fifth (21%) said it was available about half of the time, and a quarter (25%) felt it was occasionally available. A further 4% said the information was never available. Again there was an association with ease of identifying PPDS foods, those who found it easy to identify PPDS foods were more likely to find the information they need all or most of the time (59% vs 33% of those who found it difficult).

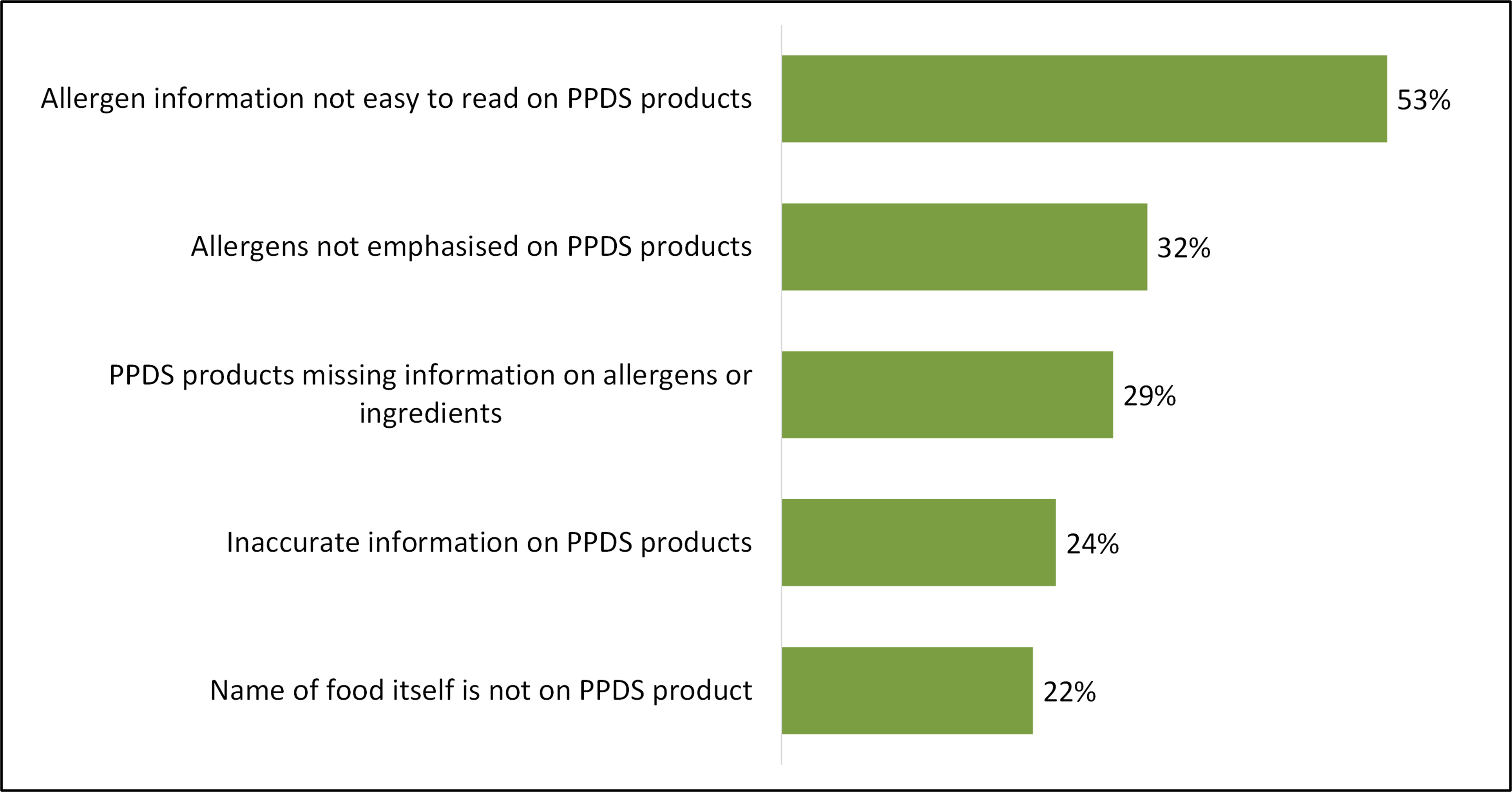

Linked to the above, since the new labelling requirements were introduced, almost two thirds (63%) of consumers who purchase PPDS had experienced issues accessing information on PPDS labels. The most common issue reported was allergen information not being easy to read (53%). This was caused by a variety of factors, including the font size on labels being too small (78% of those who reported allergen information not being easy to read) and labels being blurred or smudged (41% of those who reported allergen information not being easy to read). Other frequently encountered issues included allergens not emphasised on PPDS foods (32%) and PPDS products missing ingredients or allergen information altogether (29%).

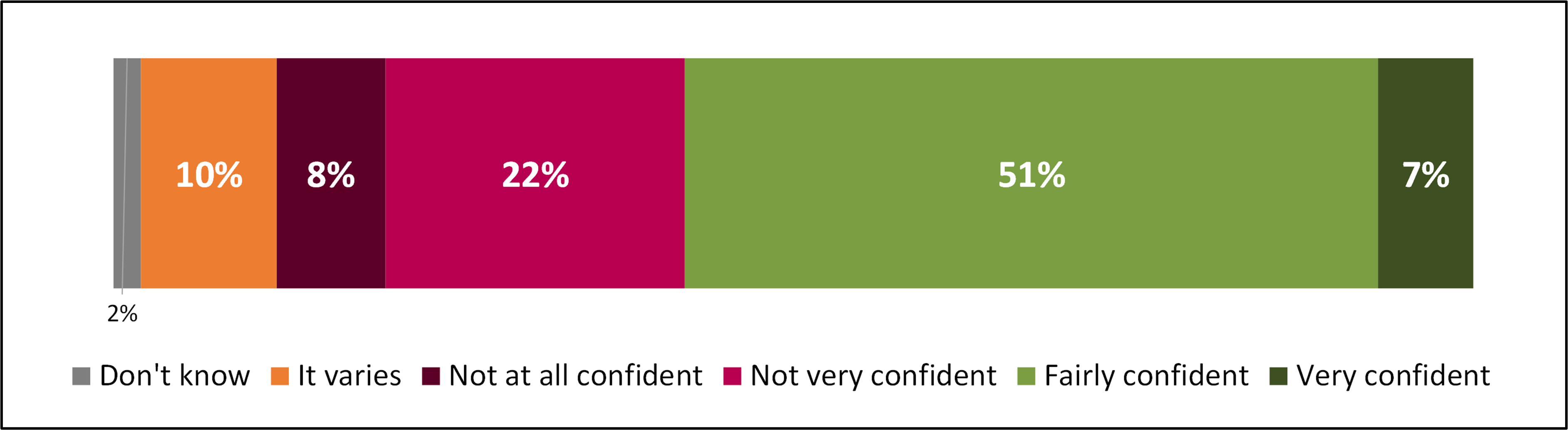

Consumer confidence in the accuracy of PPDS labelling was mixed, with 58% confident and 30% not confident. In the qualitative interviews it was clear that a number of factors influenced consumer confidence, such as the type of FBO, how familiar consumers were with the site and staff, the design of labels (e.g. whether easy to read) and levels of concern regarding allergen cross-contamination.

Compliance with PPDS labelling requirements

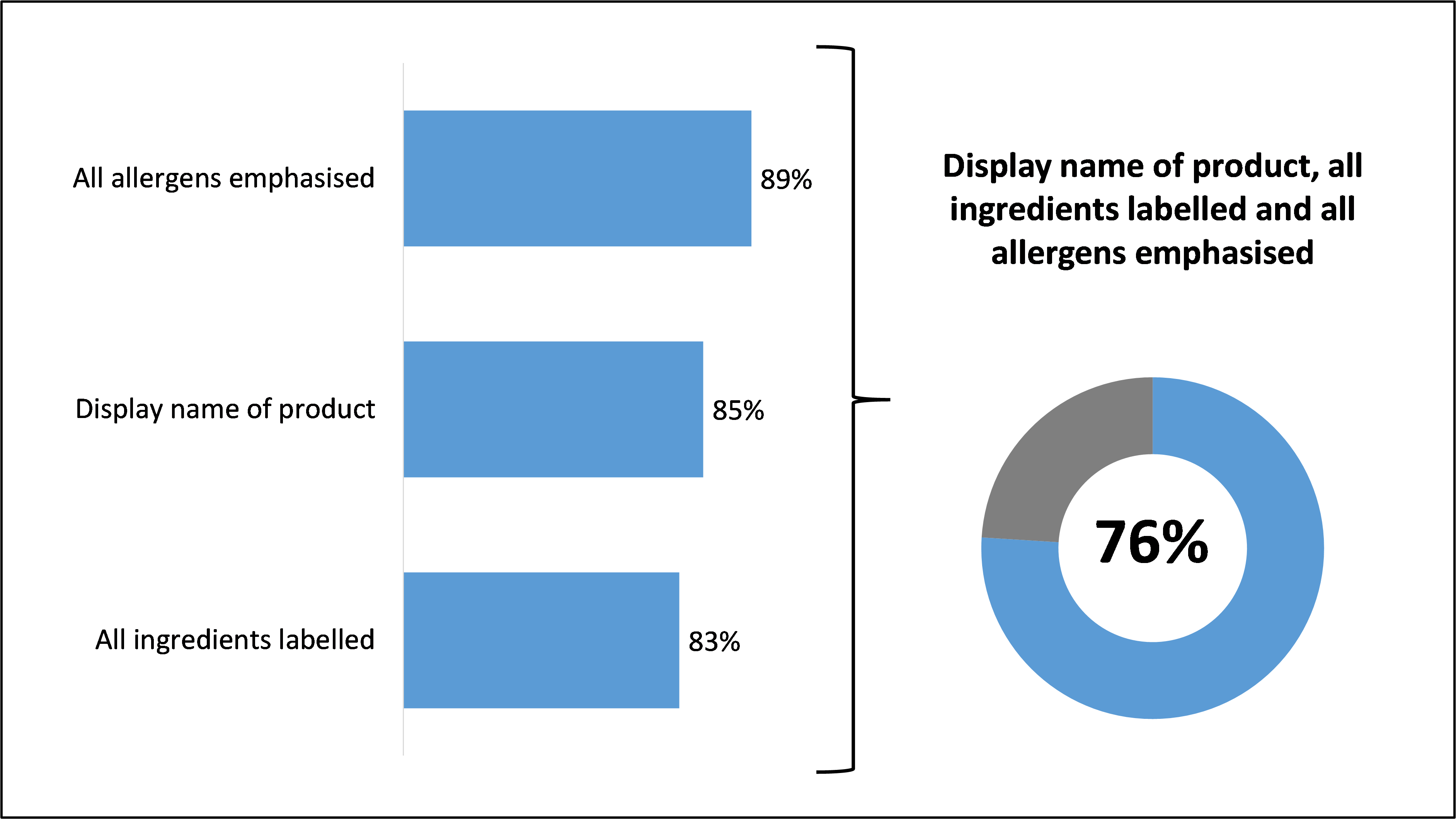

Self-reported compliance among FBOs was reasonably high, with around three quarters (76%) of those that sold PPDS foods reporting full compliance with all aspects of the legislation. In other words, they displayed the name of the product, listed all ingredients and emphasised allergens on ingredients lists. Levels of compliance across these three aspects, was highest regarding emphasising allergens (89%), with 85% displaying the name of the product and 83% listing all ingredients. When FBOs did not comply with all three aspects, this was typically attributed to low awareness and understanding of the PPDS labelling requirements.

Retailers were more likely than caterers to self-report compliance (87% vs 66%), with particularly high levels amongst butchers (92%), general retail (86%) and bakers (85%). With regards to size, the likelihood to self-report compliance increased with employee headcount; two thirds (69%) of those with between 1 and 5 employees said they were compliant compared to 80% of those with between 6 and 10 employees and 87% of those with 11 or more employees.

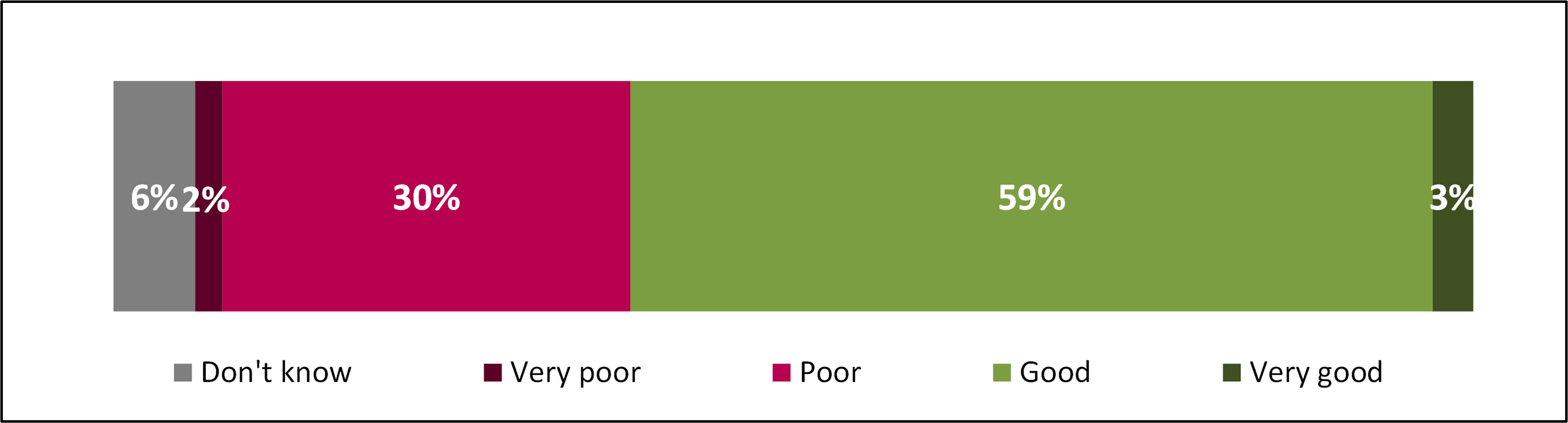

LA perceptions of compliance with the labelling requirements were slightly different to levels of self-reported compliance amongst FBOs, with 62% describing compliance amongst the FBOs where compliance checks had been conducted as ‘good’ or ‘very good’. This figure is lower than the three-quarters (76%) of FBOs who self-reported compliance. This discrepancy may be due to LAs reporting on a larger sample of FBOs, compared to FBOs who are just reporting on themselves.

Amongst those that labelled all ingredients or emphasised allergens on the packaging of PPDS food (84%, n=781), the most common way this information was presented was through labels printed in-house (64%). During qualitative interviews, many of these FBOs said they had invested in labelling software and hardware to assist with compliance. A quarter (25%) of FBOs used labels printed by a third party, while 8% used handwritten labels and 6% used labels supplied by their head office.

Across all size bands and sectors of FBOs, the printing of labels in-house was the most common method of presenting ingredients information on PPDS foods. However, there were some types of FBOs that were more likely than average to use alternative methods. With regards to size, FBOs with between 1 and 5 employees were more likely than average to use labels printed by third parties (28%), and those with 11 employees or more were more likely than average use labels supplied by their head office (10%). In terms of sector, caterers were more likely than average to use handwritten labels (14%), particularly restaurants and cafes (15%).

Almost three quarters (72%) of FBOs reported using Precautionary Allergen Labelling (PAL) on their PPDS foods. The most common reason for using PAL was to flag the risk of cross-contamination during preparation (44%), however it was also used to ‘pass on’ PAL used on ingredients sourced from suppliers and wholesalers (28%).

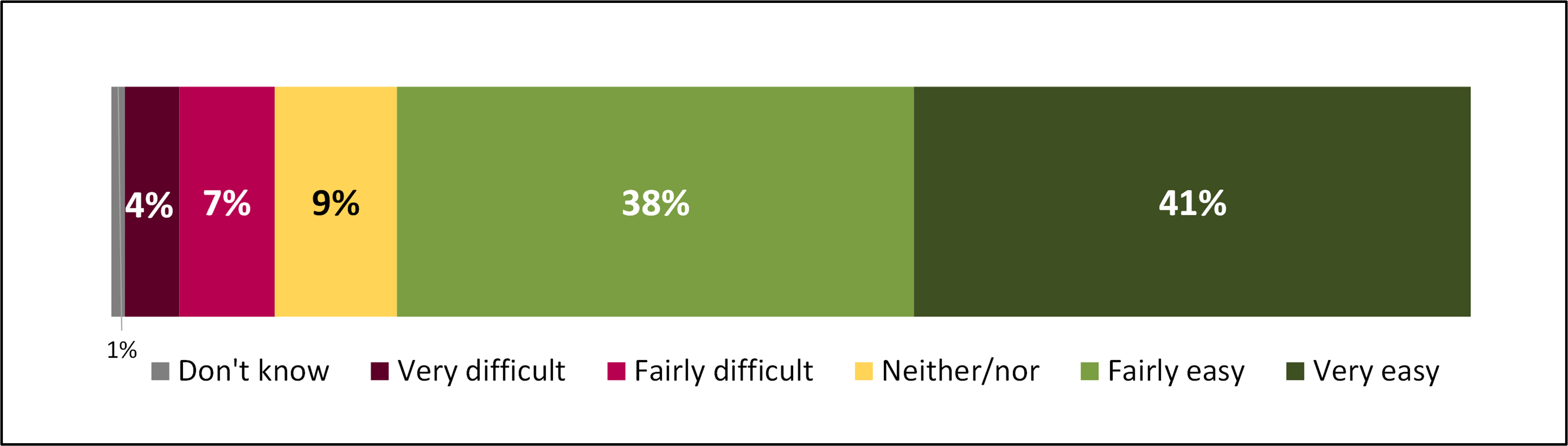

Experience of compliance

FBOs generally reported that they found compliance with PPDS labelling requirements easy (81%). FBOs in England were more likely than those in Scotland and Wales to have found it easy (82% vs 71% in Scotland and 71% in Wales). So too were retailers compared to caterers (88% vs 76%) and those with 11 employees or more compared to those with fewer (87% vs 78%). In the qualitative interviews, some FBOs who reported that compliance was easy mentioned that they had experienced some challenges initially but had managed to overcome these.

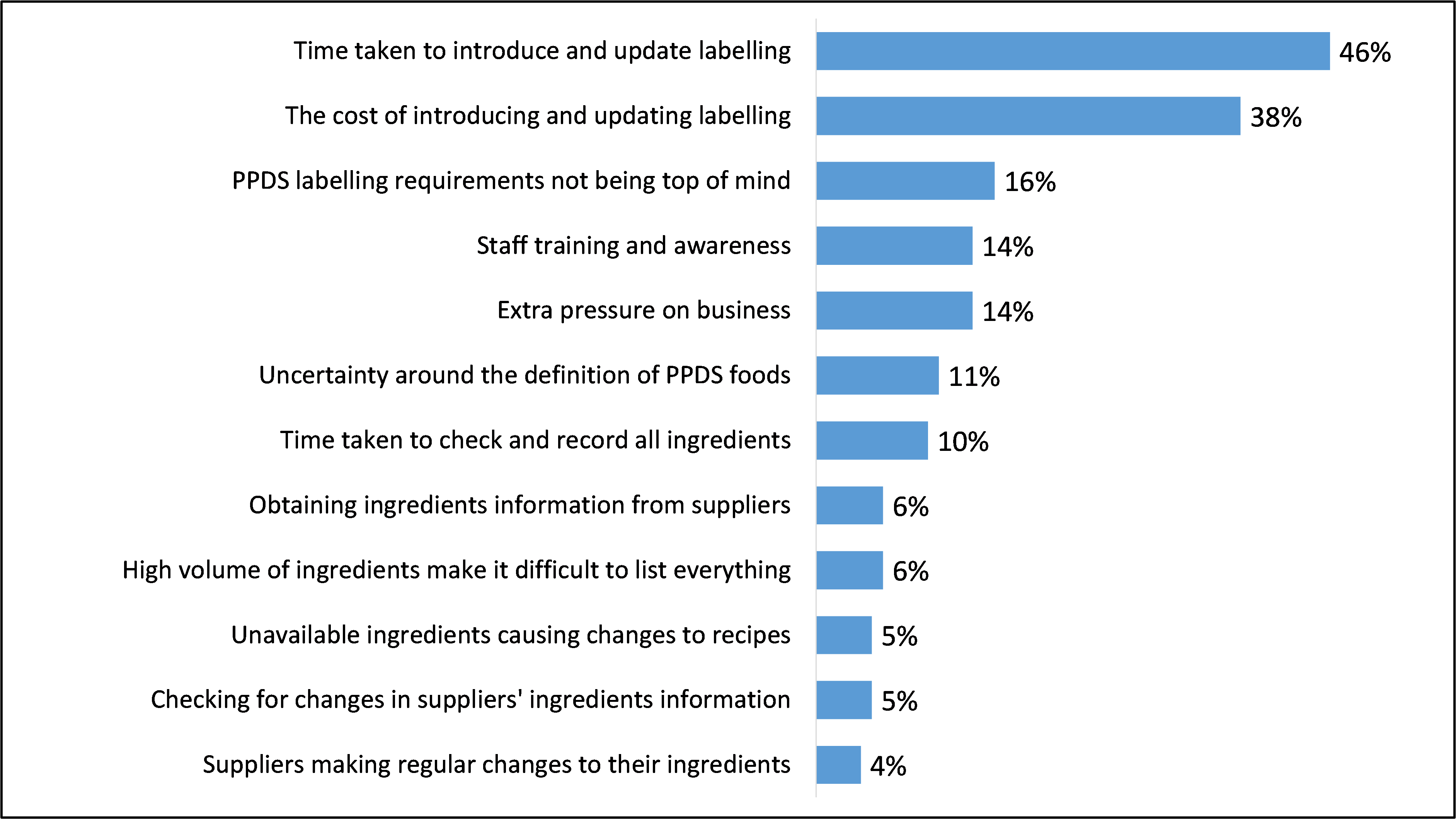

For the one in ten (11%) FBOs who indicated in the survey that they continued to find compliance difficult, the two most frequently cited reasons were the time taken to introduce and update labelling (46%) and the cost of doing so (38%). Other factors included PPDS labelling not being top of mind for the FBO (16%) and lack of staff training and awareness (14%).

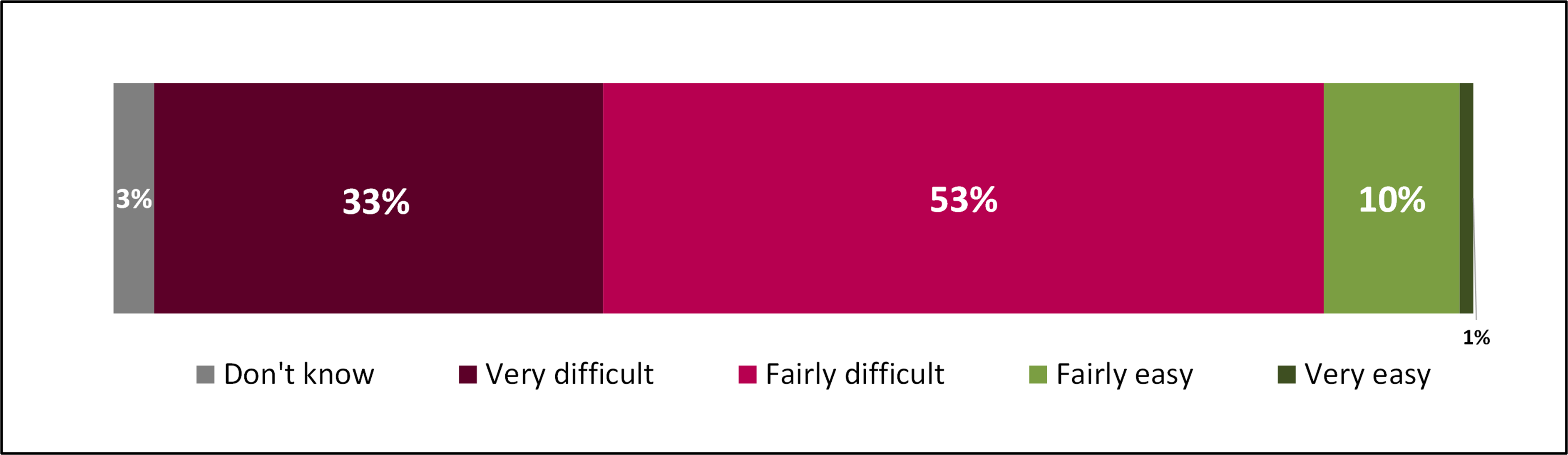

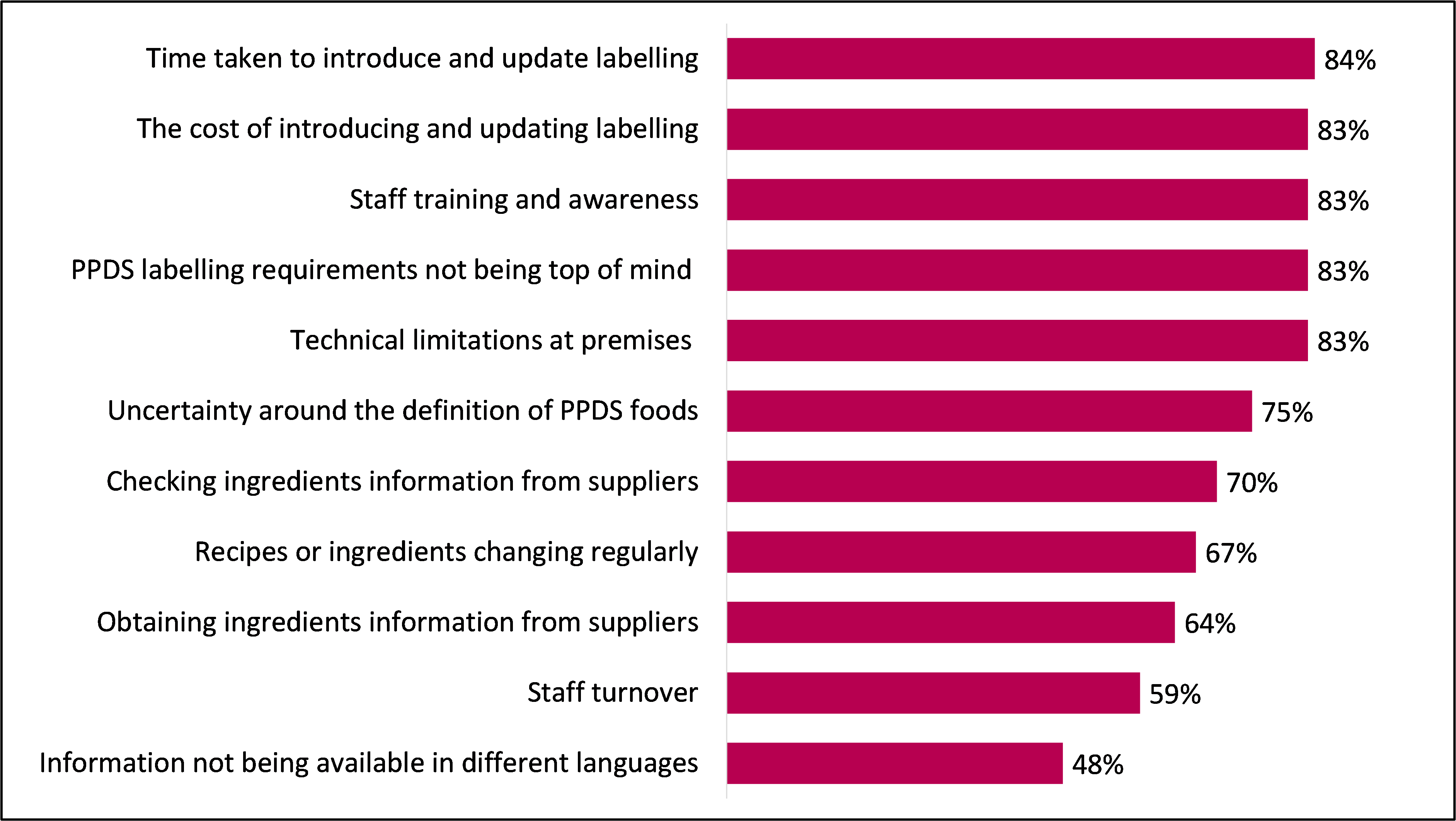

In contrast to FBOs self-reported experiences of compliance, close to nine in ten LAs (87%) felt that FBOs had found compliance with PPDS labelling requirements to be difficult. (footnote 3) Reasons given for this difficulty mirrored those given by FBOs, with the time taken to introduce and update labelling (84%) and the cost of doing so (83%) the two most frequently cited. However, LAs also mentioned causes of difficulty that were not mentioned by FBOs, notably technical limitations at the premises (83%), staff turnover (59%) and information not being available in languages others than English (48%).

Amongst the LAs that said FBOs had difficulty with compliance (87%, n=109), when prompted, around half (47%) identified smaller FBOs as those that have the most difficulty. A quarter (26%) highlighted takeaways as having particular difficulty with PPDS labelling requirements.

Support with compliance

There are various sources of support and guidance available to FBOs to learn about the PPDS labelling requirements and how to comply with them, and nearly all FBOs that sold PPDS and were aware of the new requirements (92%, n=838) had used at least one (97%).

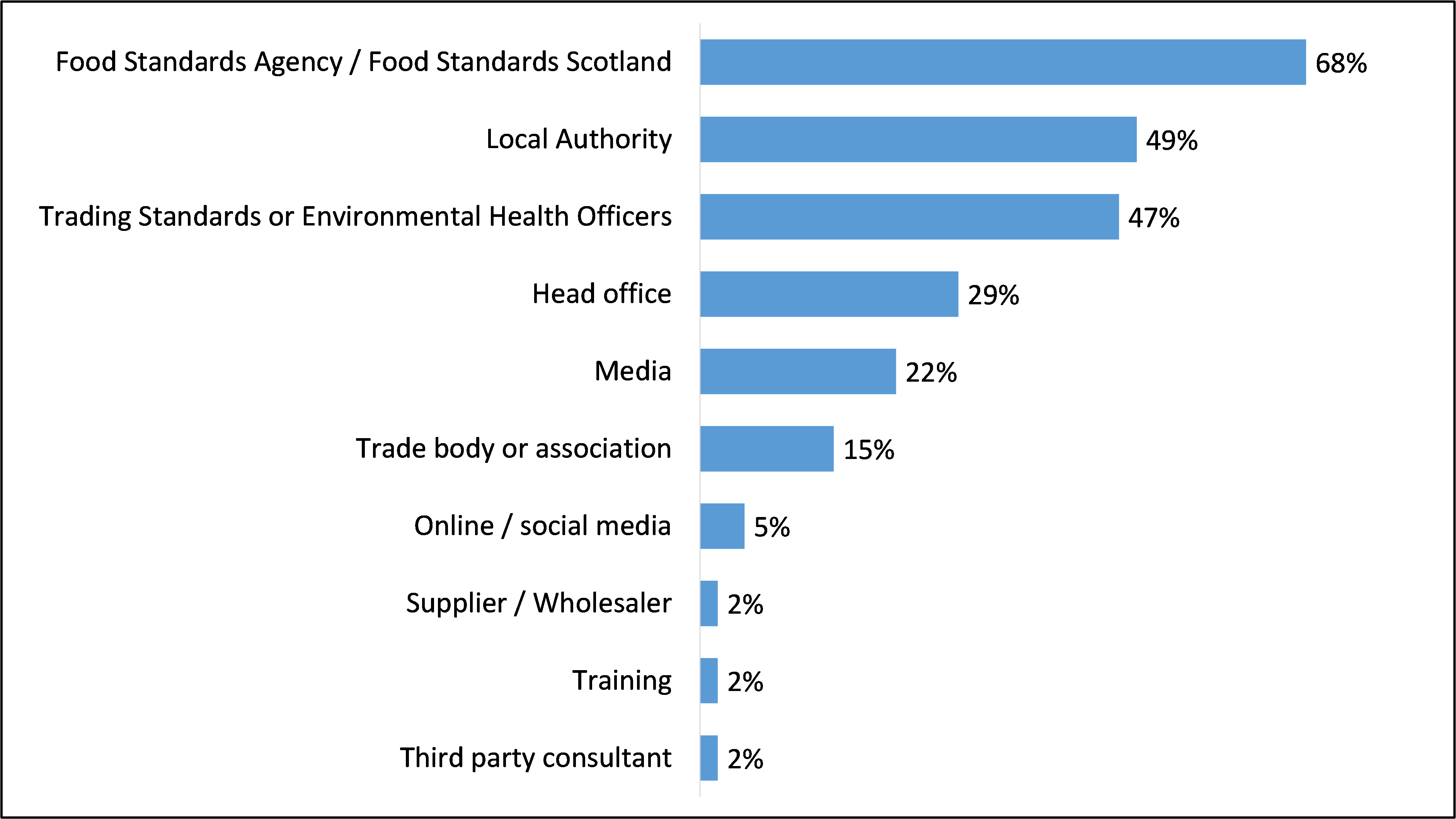

The sources most frequently mentioned by FBOs included the FSA and FSS (67%), followed by LAs (47%) and Trading Standards or Environmental Health Officers (45%). FBOs were generally very positive about the guidance accessed from the FSA, FSS and LAs, with FBOs often mentioning they had used online resources such as written guidance and videos. When FBOs received support from their LA, this often occurred at the point of a visit or inspection. In the qualitative interviews, some FBOs did not access support from the FSA, FSS and their LA, most commonly because they did not feel they needed it or sought it elsewhere, such as their head office.

In terms of appetite for support to help make compliance easier, two thirds (68%) of FBOs did not feel they needed any, due to sufficient support already available. A quarter (25%) of FBOs felt they would benefit from additional information. This was more likely amongst delicatessens (52%) and catering businesses (39%) than average, and amongst FBOs with fewer than 10 employees when compared to those with 11 or more (28% vs 19%).

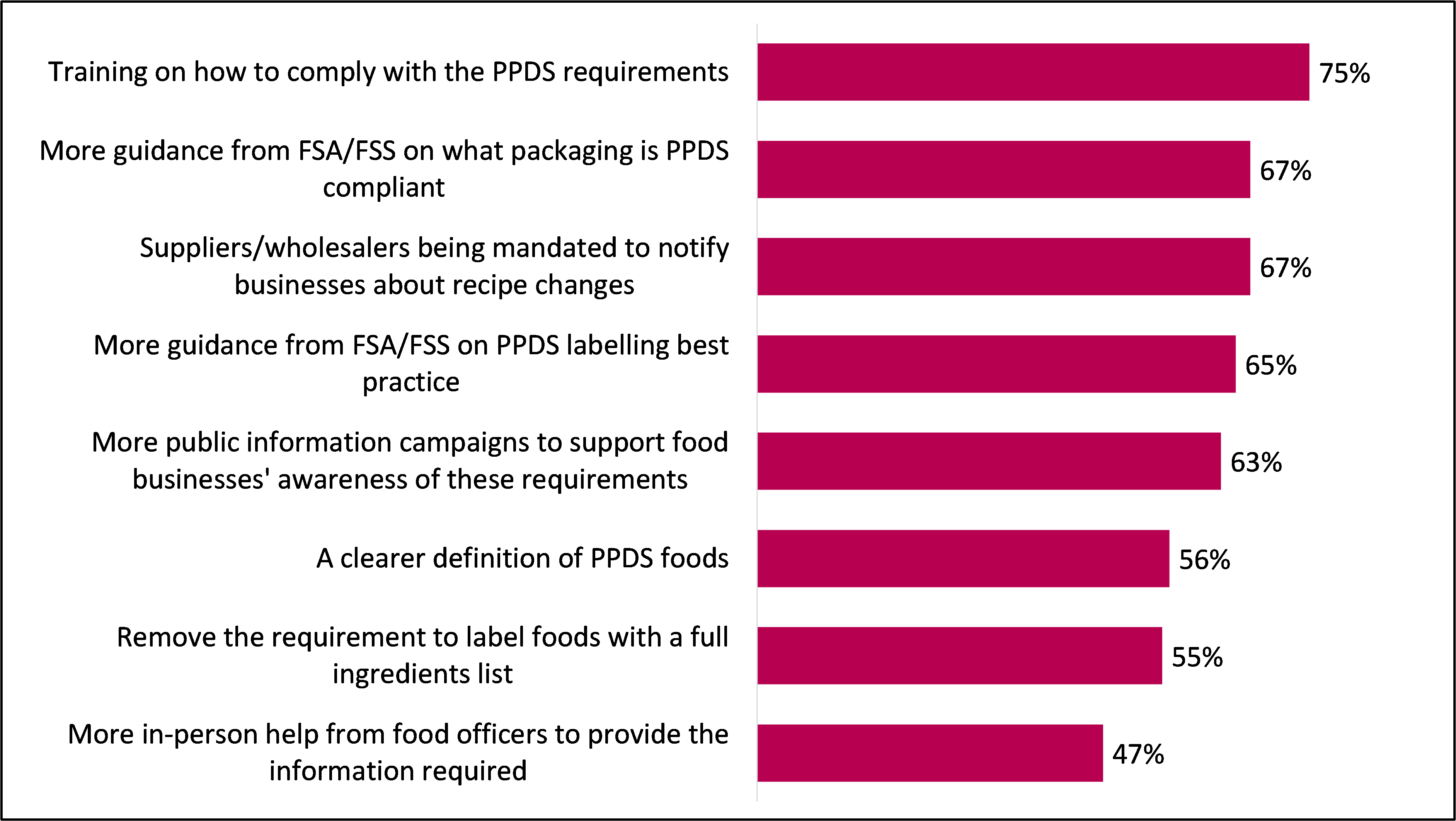

Despite a low appetite for additional support amongst FBOs, nearly all LAs felt that further action could be taken to make it easier for FBOs to comply with new labelling requirements (95%). These actions often related to additional support and guidance, with three quarters (75%) suggesting general training on how to comply with the requirements, and two thirds identifying a need for more guidance from the FSA and FSS on compliant packaging (67%) and best practice in terms of labelling (65%).

In addition, some LAs suggested that the PPDS labelling requirements should be altered. Two thirds (67%) said that suppliers and wholesalers should be mandated to notify businesses about recipe changes, and more than half (55%) said that the requirement to label PPDS foods with full ingredients lists should be removed, with the emphasis of the legislation being placed on allergens instead.

Compliance checks

LAs support FBOs with legislative requirements and generally have responsibility for the enforcement of food information legislation. (footnote 4) Almost all LAs that participated in this research had checked FBO compliance regarding PPDS labelling requirements since they were introduced in October 2021 (98%). The small minority (2%) of LAs that had not conducted compliance checks explained that this was because their team was not responsible for checking food business compliance.

Compliance checks were often conducted as part of routine food safety inspections (95%). 71% of LAs had also conducted reactive PPDS inspections (e.g. in response to complaints from consumers) and half (51%) conducted visits specifically focused on PPDS foods.

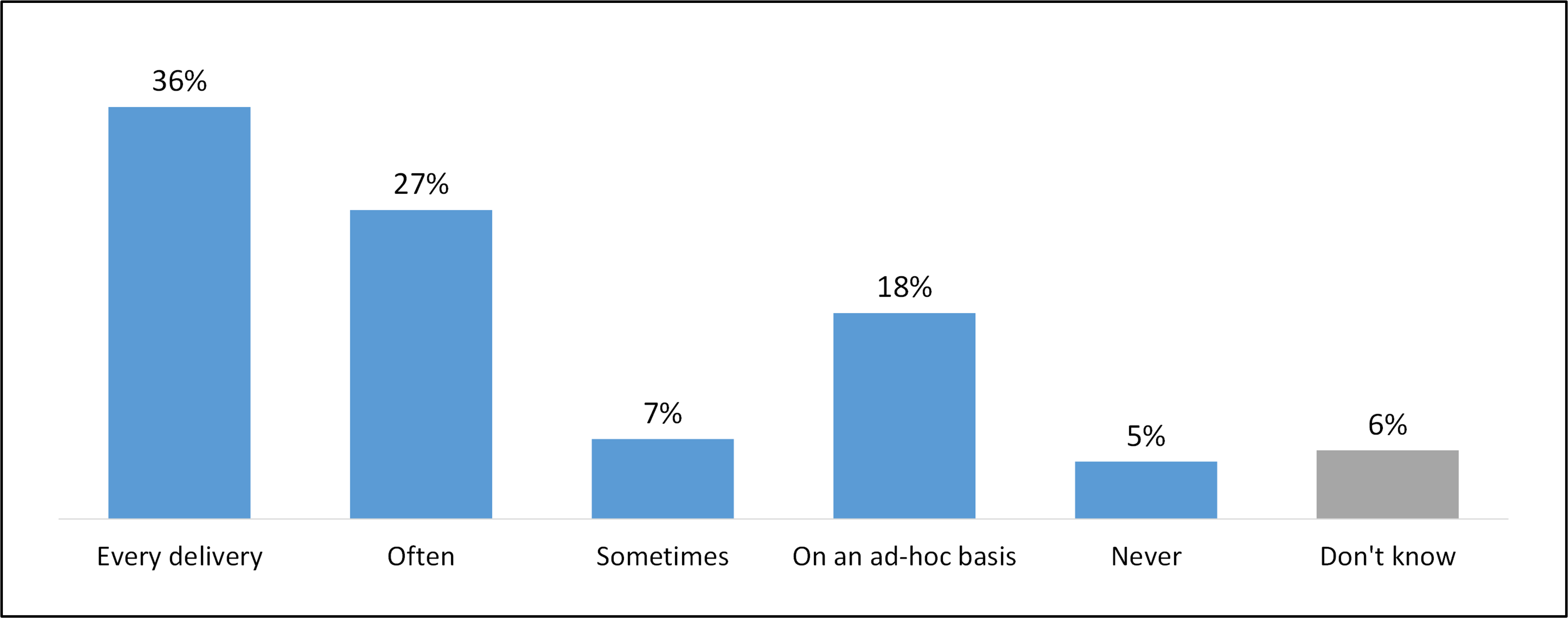

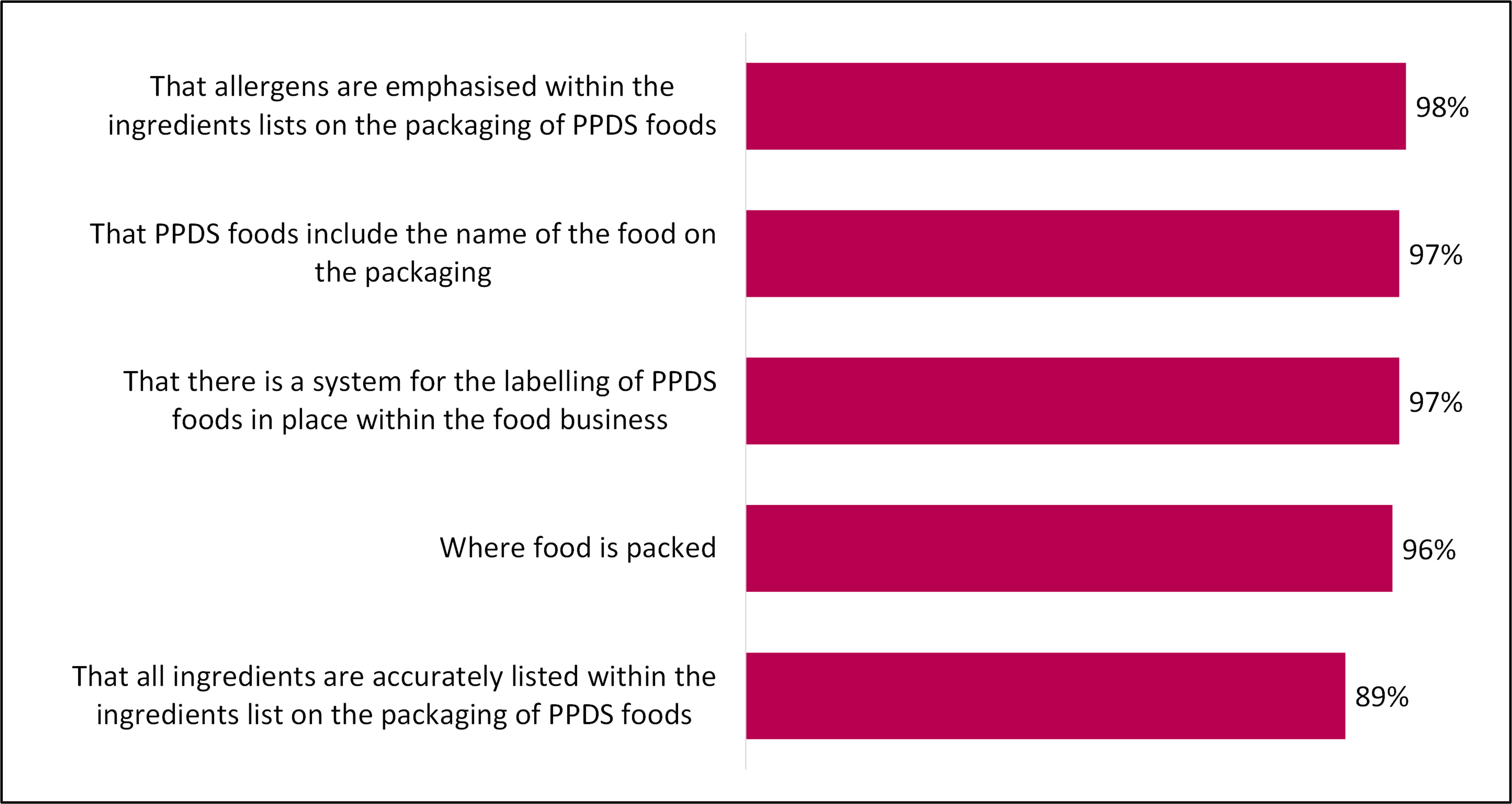

LAs reported checking various aspects of the PPDS labelling requirements during visits to FBOs. Nearly all LAs checked that allergens are emphasised in ingredients lists (98%), that the name of the food is displayed on packaging (97%), that there is a system for labelling in place (97%) and checked where food is packed (96%). In addition, 89% checked that all ingredients are accurately listed with the ingredients lists of PPDS packaging.

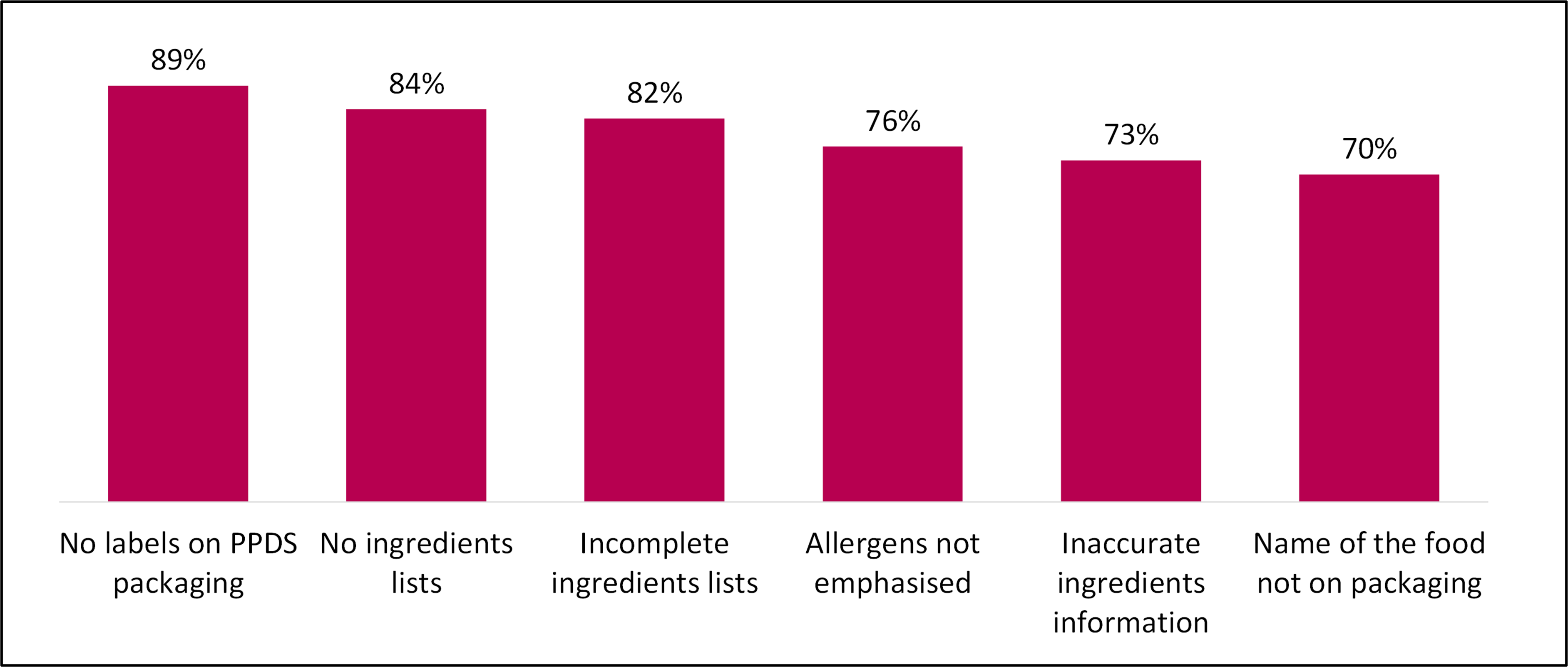

In the first year since the introduction of these legal requirements, nearly all LAs had encountered at least some cases of non-compliance (95%). Close to nine in ten LAs had observed there being no labels on the packaging of PPDS foods (89%), and more than four fifths had observed no ingredients lists (84%) and incomplete ingredients lists (82%).

Some LAs reported escalating incidents of non-compliance and taking enforcement action; written warnings had been issued by 40% of LAs, improvement notices had been issued by 8% and cautions had been issued by 2%. However it was more common for LAs to respond by signposting FBOs to guidance or support (91%) or by providing written (86%) or verbal (84%) advice. Many LAs explained that their focus for the first year of the PPDS labelling requirements had been to educate FBOs and support them with compliance rather than pursue enforcement.

A quarter (25%) of LAs found compliance checks difficult. The main reasons for this were: not having enough internal resource to visit and inspect all businesses to check for PPDS compliance (n=21/31), uncertainty around the definition of some or all PPDS foods (n=20/31) and difficulty checking the accuracy of PPDS ingredients lists (n=14/31). These sources of difficulty were also highlighted as challenges amongst those that reported finding compliance checks to be easy overall.

Amongst the LAs that had conducted compliance checks and found the process less than ‘very easy’ (87%; n=109), the top three things that they felt would make compliance checks easier were: more resources for LAs (e.g. funding and staff) (29%), greater clarity on what food products are covered by PPDS labelling requirements (22%) and materials for LAs to share with FBOs (e.g. guidance handouts) and issue to FBOs (e.g. improvement notices) (21%).

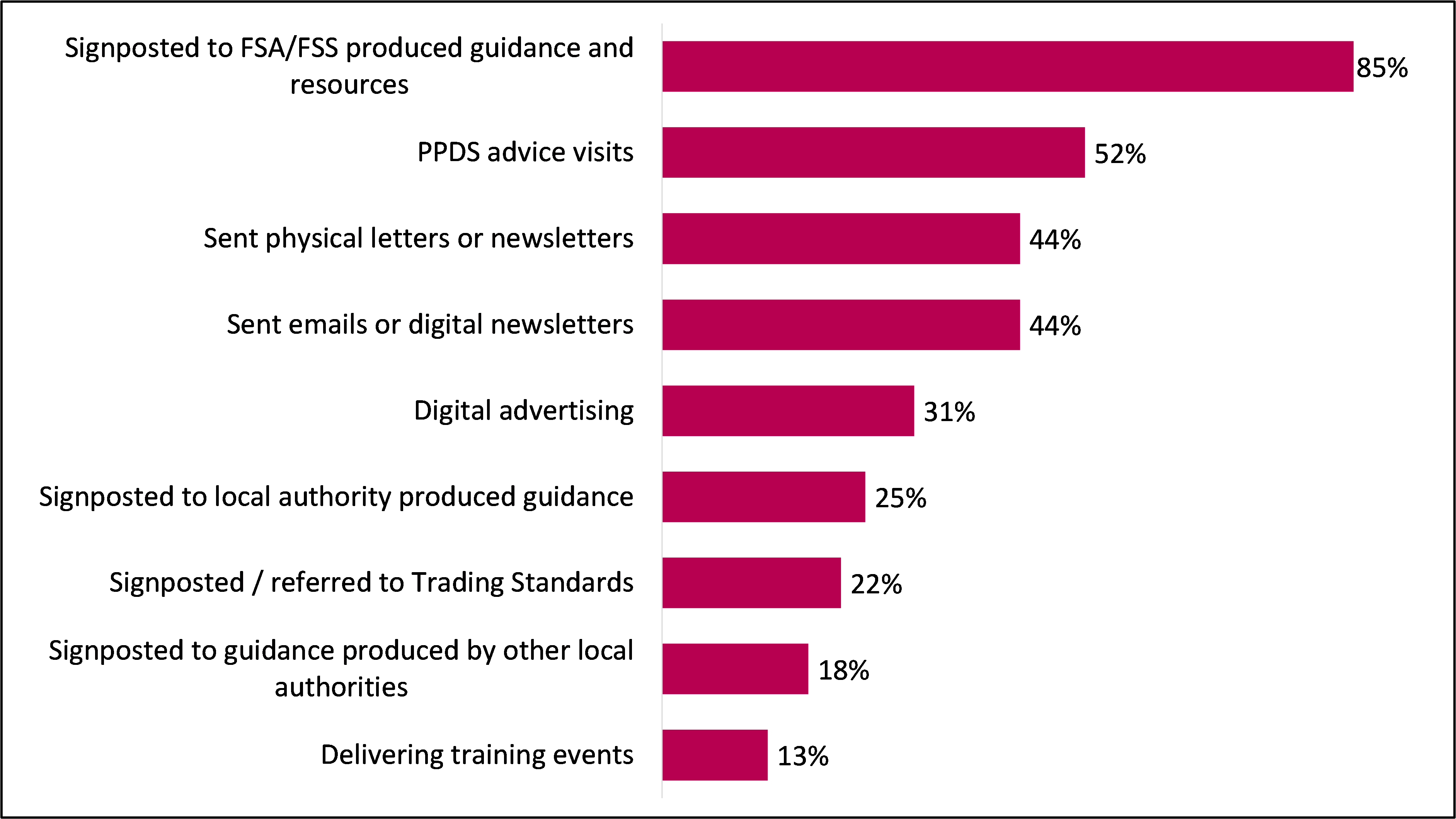

Nearly all LAs (99%) stated that they had conducted activities to support and increase compliance with PPDS labelling requirements since they were introduced. The most common activity was signposting to FSA and FSS guidance and resources (85%). Other actions included PPDS advice visits (52%), physical letters or newsletters (44%) and emails or digital newsletters (44%). LAs indicated in the qualitative interviews that they had typically undertaken a blanket approach to these activities. However, some took a targeted approach and focused their activities on FBOs where PPDS labelling was thought to be most relevant, such as bakers and butchers. Where LAs had not conducted activities, or conducted them to a lesser extent, this was generally due to a lack of resources.

Effect of PPDS labelling requirements

Effects on consumers

Findings from this research suggest that some consumers have seen positive impacts from the implementation of PPDS labelling requirements, but there is still a way to go. Where there have been positive effects of PPDS labelling requirements, these were more pronounced amongst younger consumers.

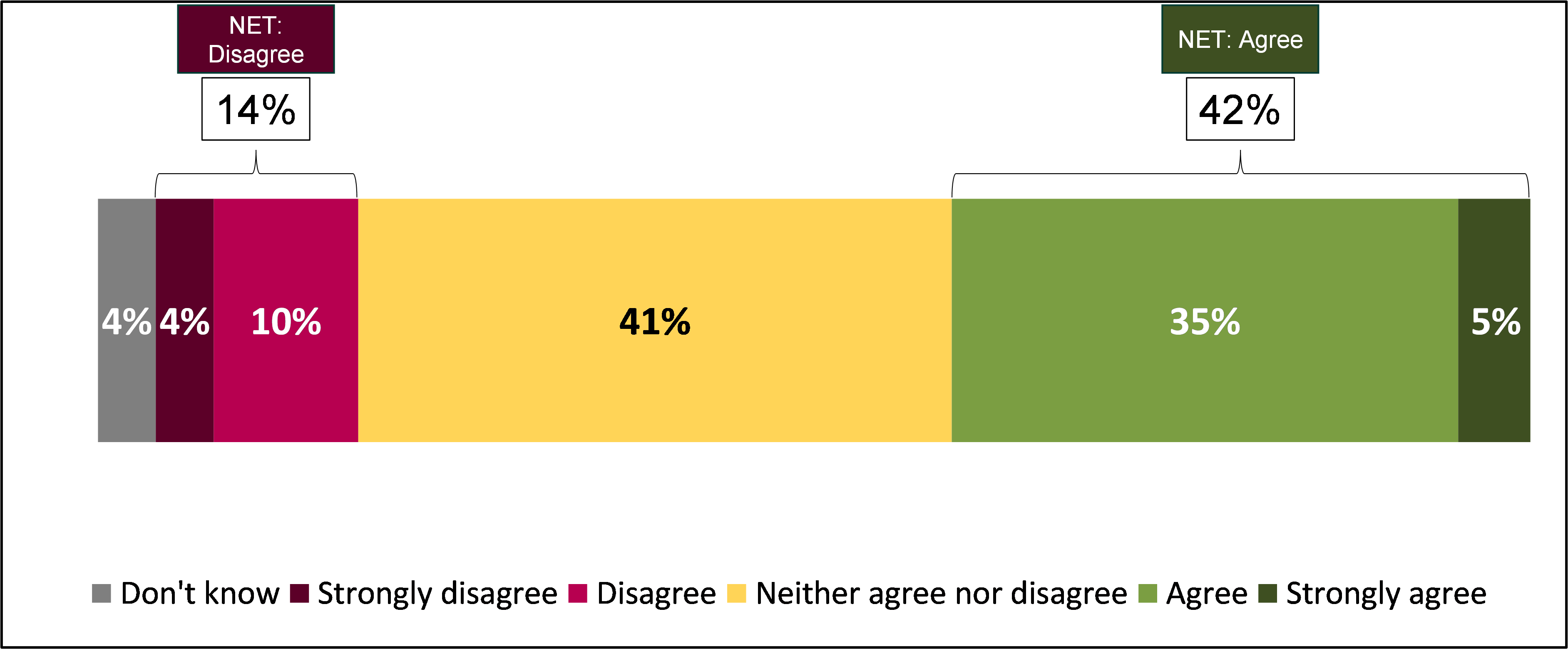

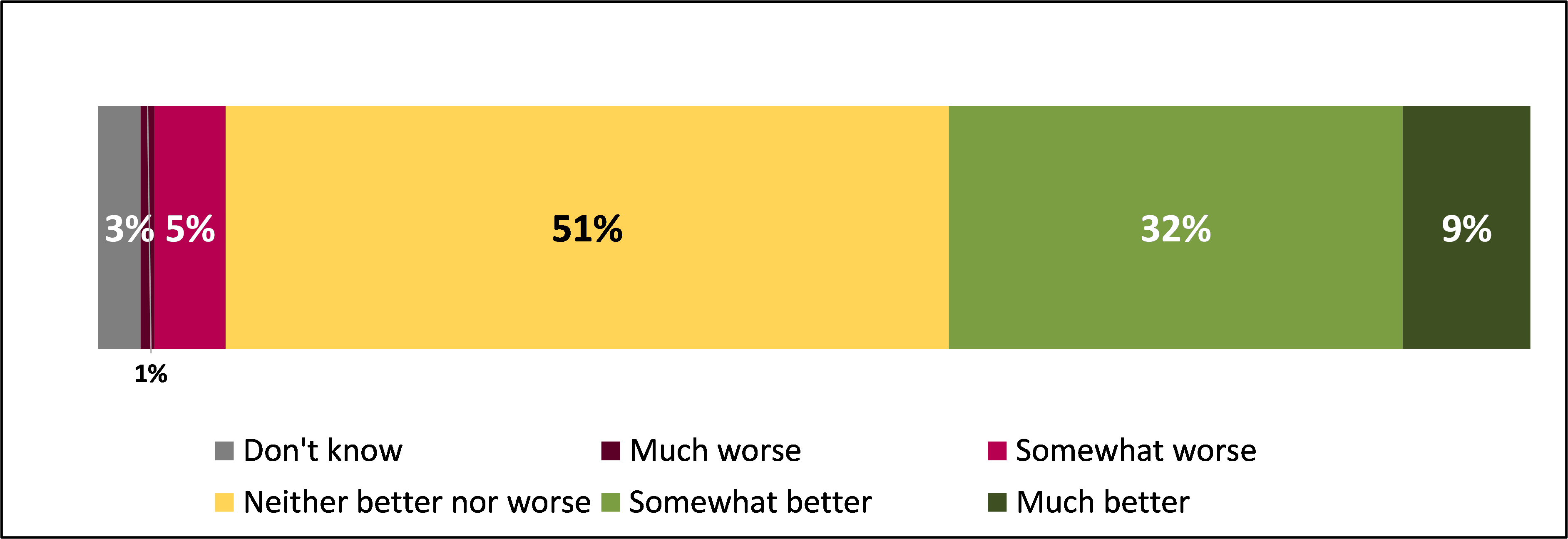

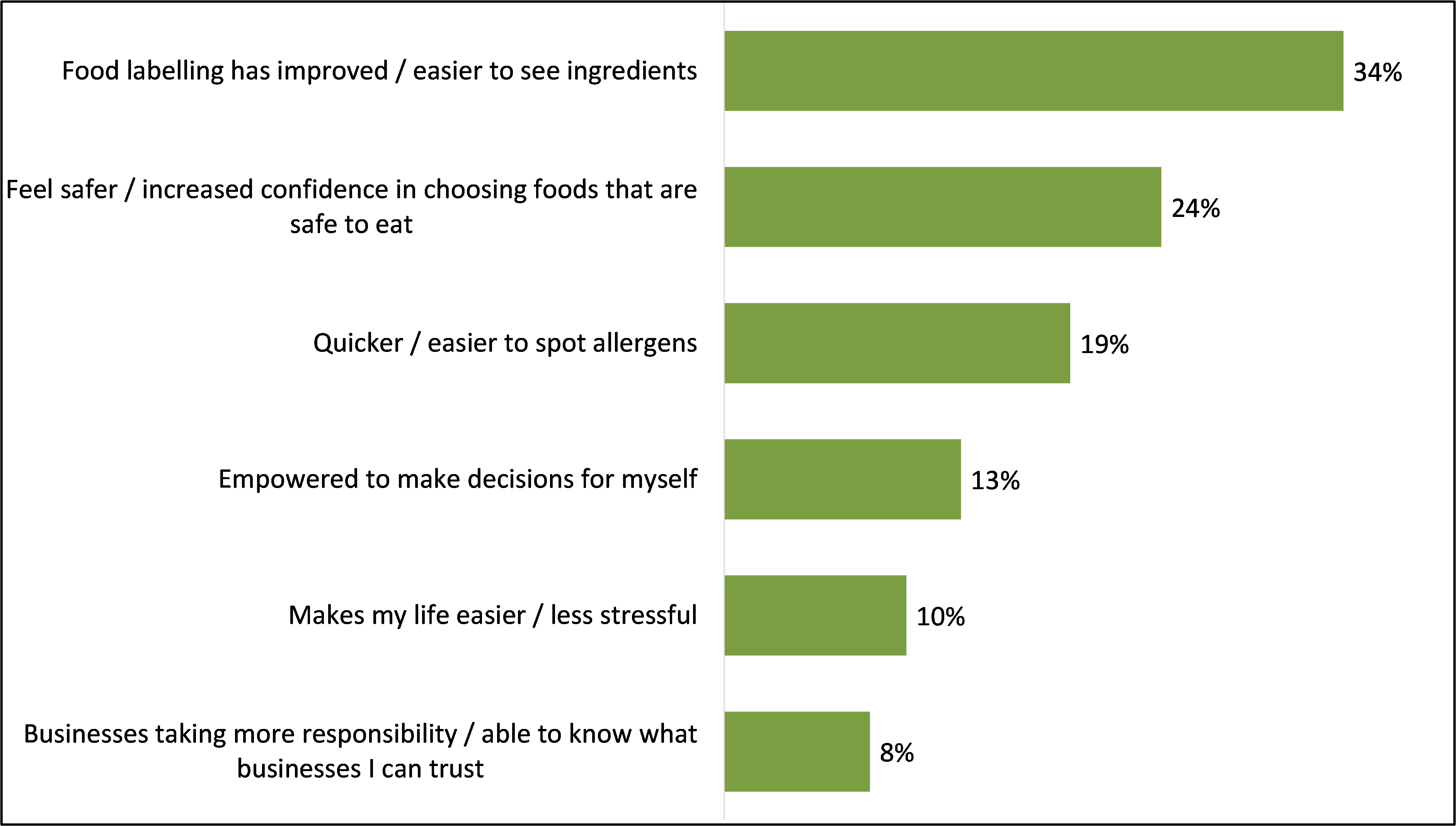

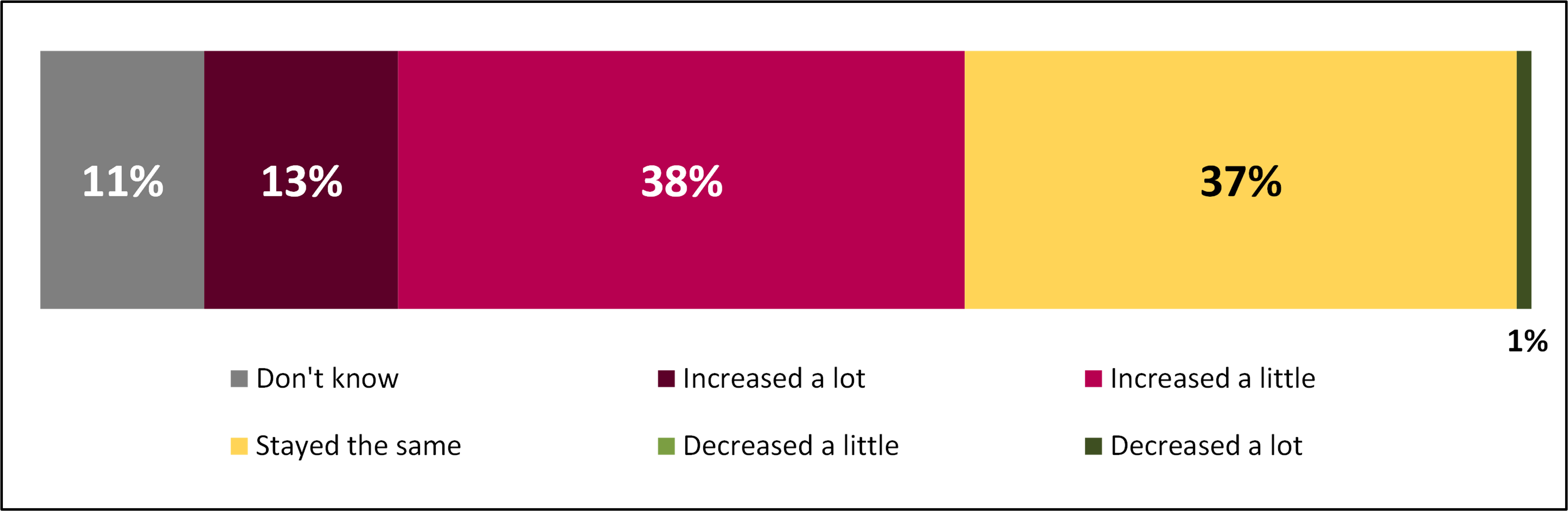

Just over two fifths (42%) of consumers felt that the availability of information needed to identify a food that may cause an unpleasant reaction had improved since October 2021. Younger consumers and more frequent purchasers of PPDS foods were more likely than average to report an improvement in the availability of information. Over half of those aged between 18 and 34 (52% vs 40% of those 35-64 and 65 and over) and those that purchased PPDS foods at least sometimes (51%vs 36% who purchase PPDS rarely or never) reported an improvement.

In addition, two-fifths (40%) of consumers agreed that their confidence in buying PPDS foods had increased since the PPDS labelling requirements were introduced. Consumers aged between 18 and 34 were more likely than older to have increased confidence (51% vs 40% of 35-64 years old and 36% of over 65 year olds). Furthermore, those who considered there to have been an improvement in the availability of information were more likely than average to purchase more PPDS foods since October 2021 (31%).

Two-fifths (40%) of consumers reported an improvement in their quality of life since the introduction of the PPDS labelling requirements. Consumers aged between 18 and 34 (43%) and those who purchased PPDS foods sometimes or often (48%) were more likely than average to report an improvement in their quality of life, alongside consumers with a child or children with a food hypersensitivity (50%) and those with an allergy or intolerance other than Coeliac disease (43%).

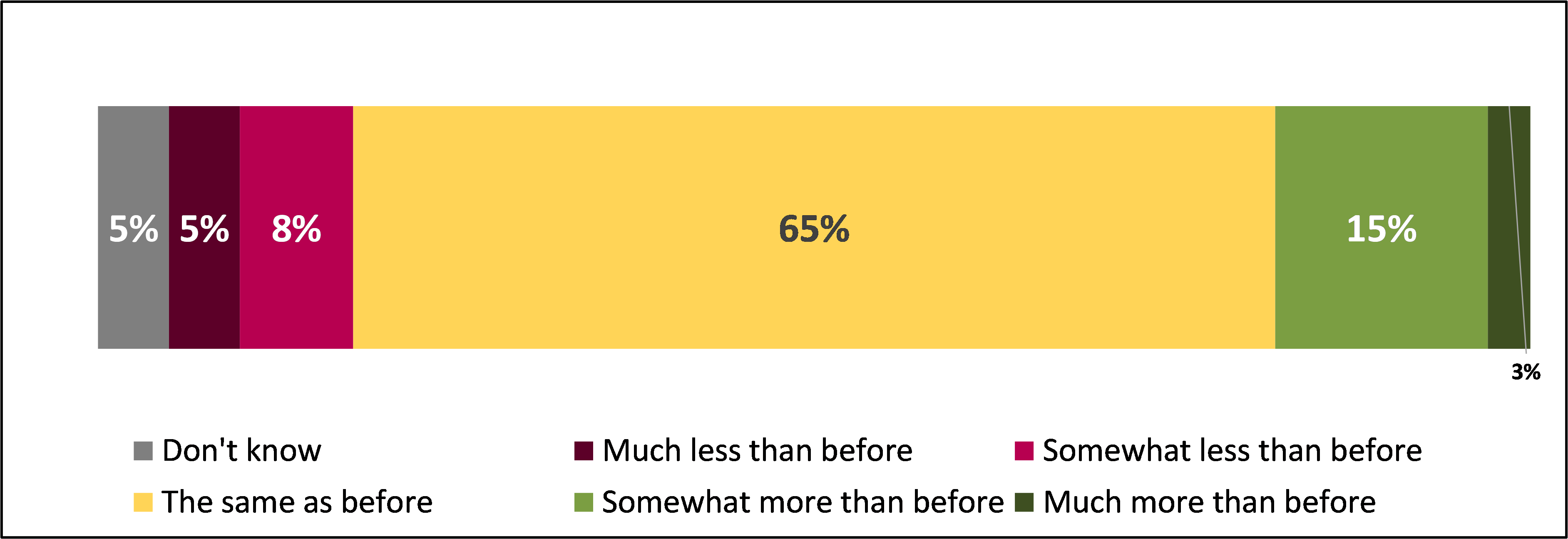

However, despite some changes in the perceived availability of ingredients information and confidence in buying PPDS foods which increased for around two-fifths of consumers, this did not often translate to behaviour change. Only a minority (17%) of consumers reported purchasing PPDS foods more often since the introduction of PPDS labelling requirements. Further exploration in the qualitative interviews showed that this was often due to concerns about the risk of cross-contamination.

Perceived changes in the availability of ingredients information on PPDS foods appears to be associated with the purchasing frequency of consumers, with those who felt there had been an improvement in this availability more likely than those who felt availability had stayed the same or got worse to purchase more PPDS foods (31% v 8% and 6% respectively).

The nature and severity of food hypersensitivities was also associated with the likelihood to buy PPDS foods more often since the introduction of labelling requirements. Specifically, consumers with severe allergies or intolerances (19%), consumers whose child had a food hypersensitivity (24%) and those with an allergy or intolerance other than Coeliac disease (20%) were more likely than average to purchase PPDS foods more often than before October 2021.

Effects on FBOs

For FBOs, the implementation of PPDS labelling requirements led to some changes and increased costs, though for others impacts were more minimal. There was evidence that the implementation of PPDS labelling requirements had affected the types of food some FBOs sold and their approach to serving FHS consumers. In addition, half of FBOs reported increased operating costs and administrative burden following the implementation of PPDS labelling requirements.

Half of FBOs (50%) stated that the new labelling requirements had increased their costs, mostly due to investment in equipment or materials and time spent preparing and applying labels. During qualitative interviews, most FBOs that had experienced an increase in costs explained that the most significant cost was the initial outlay on hardware and software. Many continued to face higher costs (e.g. the cost of materials and staff time to prepare and check labels of packaging) following this initial investment, but these were less significant that the set-up costs and did not pose an issue to the survival of the business.

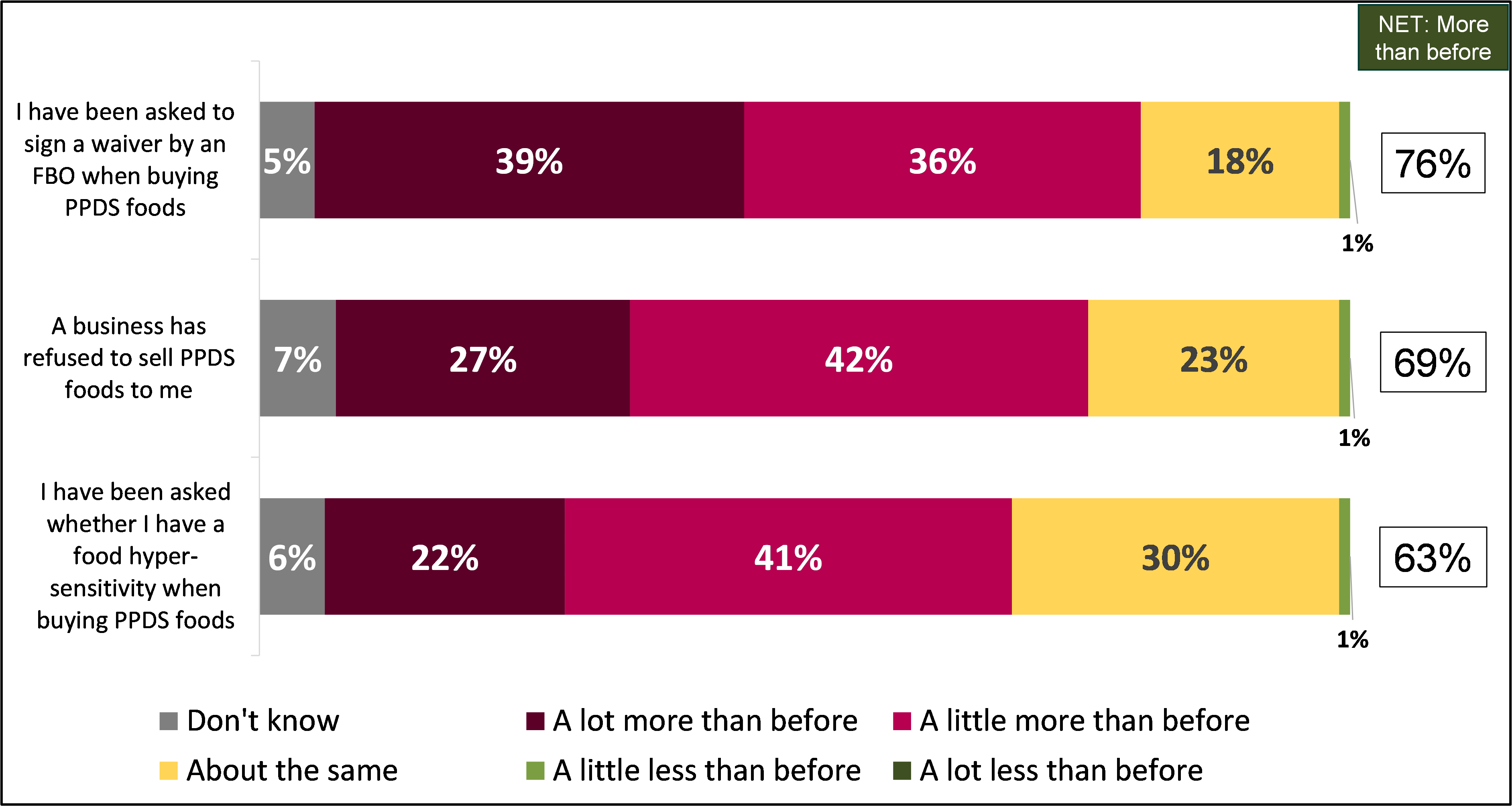

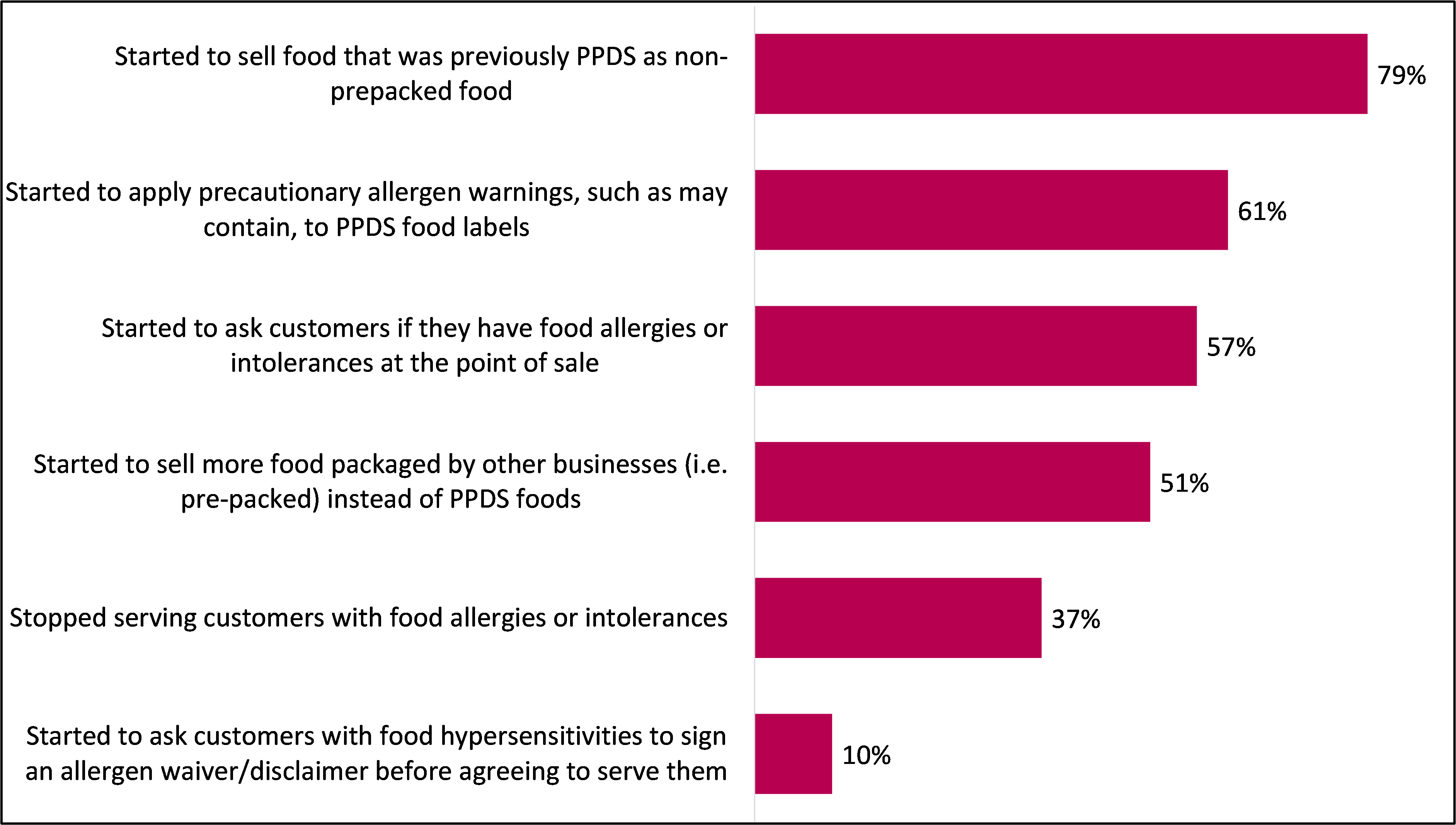

A larger impact on FBOs related to their business practices, with eight in ten (81%) FBOs that sold PPDS foods reporting that they had made some changes to their business practices since the introduction of the labelling requirements. Most commonly, this was applying Precautionary Allergen Labelling (PAL) to their PPDS foods (59%) and starting to ask customers if they had food allergies or intolerances at the point of sale (41%). These changes had also been widely observed by LAs, with 61% reporting FBOs starting to apply PAL to their PPDS foods and 57% starting to ask customers if they had food allergies or intolerances at the point of sale.

Over a quarter (26%) of businesses changed the foods they sell, with 17% selling food that was previously PPDS as non-prepacked food, and 16% starting to sell more food packaged by other businesses. LAs were much more likely to have observed FBOs starting to sell food that was previously PPDS as non-prepacked food (79%) and FBOs starting to sell more food packaged by other businesses instead of PPDS foods (51%).

FBOs that had started to sell more prepacked and non-prepacked foods since the introduction of PPDS labelling requirements explained that the reason for this was to remove certain products from falling within the PPDS labelling requirements. The justification behind this was that the business would be unable to take on the additional administration and costs of packaging and labelling all PPDS products.

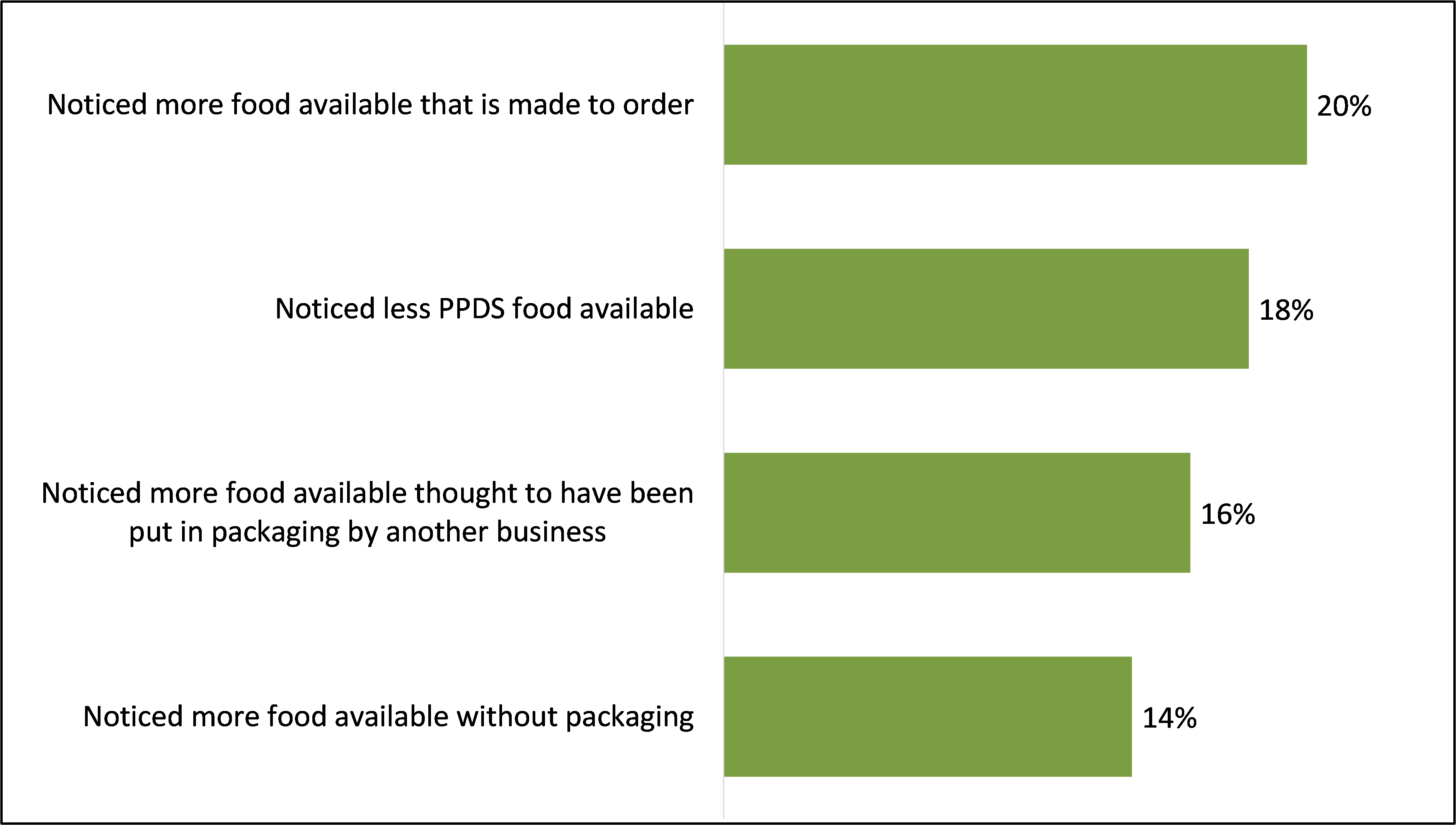

Most consumers (60%) had not noticed any changes in FBO behaviour since the PPDS labelling requirements were introduced. Where changes had been observed, the most common were an increase in the availability of food made to order (20%) and a reduction in the availability of PPDS foods (18%). Some consumers had observed food that was previously sold as PPDS being packaged differently, 16% noting an increase in prepacked food and 14% noting an increase in non-prepacked food.

A small proportion (9%) of FBOs that participated in the research did not sell PPDS foods at the time of the survey but had done in the past 12 months. A fifth (20%) attributed this to the introduction of PPDS labelling requirements, though change in customer preference (32%) and resource pressures (25%) were more common reasons.

Impact of new labelling requirements on LAs

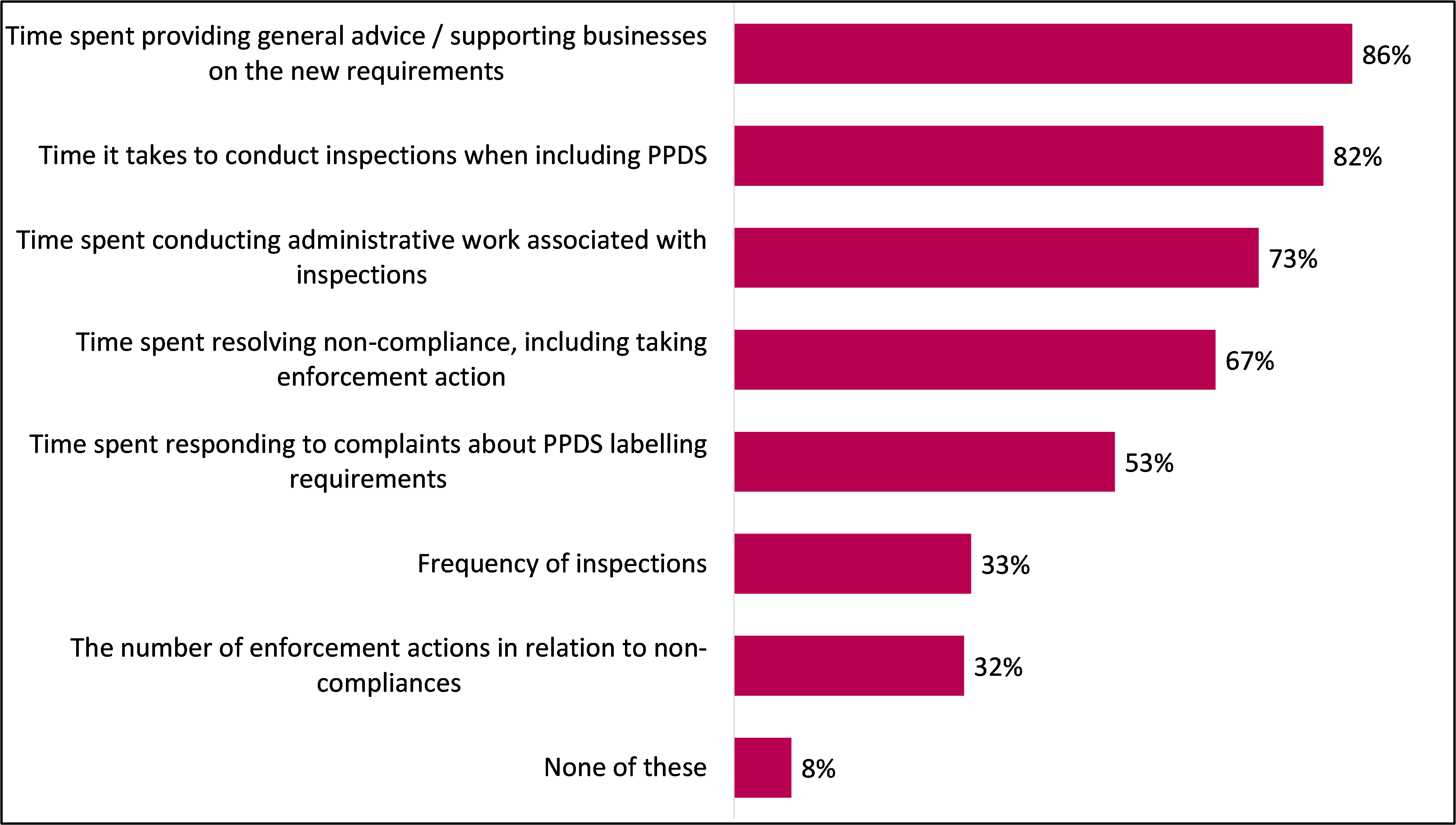

Most LAs (92%) reported an increase in at least one aspect of their work following the introduction of the new PPDS labelling requirements. This was most often in time spent providing advice and supporting businesses (86%), time taken to conduct inspections when including PPDS (82%), time spent conducting administrative work associated with inspections (73%) and more time on resolving non-compliance and taking enforcement action (67%).

Amongst those that reported an increase in time spent conducting inspections, conducting administrative work associated with inspections and conducting enforcement/follow up action. This was typically estimated to take a maximum of 30 minutes longer per inspection.

-

Full sample breakdowns are included in Chapter 3: Methodology and sample profile, and further explored in the separate technical report.

-

In two LAs, two staff members took part in the survey. The methodology involved the survey being sent out to LAs as an open link, meaning it could be accessed by multiple staff at the local authority, leading to these multiple completions.

-

It should be noted that LA views on the extent to which FBOs have found compliance to be easy or difficult are not directly comparable to the self-reported experience of FBOs. The perceptions of LAs were based on observations made across multiple PPDS inspections, and there is a potential for them to be skewed by instances of non-compliance. Conversely, there is a possibility that the accounts of FBOs are influence by a self-report bias.

-

The only exception to this are District Councils in England, who do not have food standards enforcement powers.

| Technical term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Coeliac disease | An autoimmune disease where eating gluten causes the immune system to begin attacking the sufferer’s own bodily tissues in the gut. This can cause diarrhoea, weight loss, fatigue, bloating, and anaemia. |

| Food Business Operator (FBO) | The natural or legal persons responsible for ensuring that the requirements of food law are met within the food business under their control. FBOs were surveyed and interviewed for this study. |

| Food hypersensitivity | Eating certain foods or additives can lead to a bad physical reaction in some people. This food hypersensitivity can involve the immune system, in which case it is called a food allergy. Food hypersensitivity is the term used to encompass a food allergy, intolerance or coeliac disease. |

| Local Authority (LA) | The local organisation that is responsible for providing public services and facilities for a geographical area; a local council. |

| Non-prepacked food | These are foods that do not fall into the definition of pre-packed foods – they are sold unpackaged to customers or packaged on the sale premises only at the customer’s request. They are also referred to as loose foods. For example, loose fruits at a greengrocer’s or a meal in a restaurant. |

| Precautionary Allergen Labelling (PAL) | Food labelling that provides information about the potential presence of allergens that may unintentionally appear in food as a result of cross-contamination. This kind of labelling is currently not legislated but is done voluntarily by food producers. |

| Pre-packed foods | These are foods that are manufactured and packaged before being transported to outlets to be sold. For example, a packet of dried pasta on a supermarket shelf. |

| Pre-Packed for Direct Sale (PPDS) | Foods made and packed on the same premises as they are being sold before being offered for sale to customers. This could include, for example, cakes, pies and sandwiches which are made and packaged at the same premises from which they sold. Since 1 October 2021, it is a legal requirement for PPDS foods to clearly display the name of the food and a full ingredients list with allergens emphasised on packaging/labelling. |

Background to the PPDS labelling requirements

The Food Standards Agency (FSA) plays an important role in ensuring safeguarding of public health, namely protecting consumers in relation to food. Similarly, Food Standards Scotland (FSS) is the public sector body for food and related safety for Scotland. Part of these organisations’ work encompasses protecting members of the public with food hypersensitivities. This includes those with food allergies, intolerances, and Coeliac disease.

The FSA and FSS work with the food industry to ensure that consumers can identify what food they can safely eat through labelling on food items. In terms of packaging, there are three key types of food that is sold to consumers:

- Prepacked foods: foods put into packaging at a different location to where it is sold. For example, bags of crisps, breakfast cereals and ready meals.

- Foods prepacked for direct sale (PPDS): foods that are packed before being offered for sale by the same food business on the same premises or location (or from moveable or temporary premises). For example, sandwiches placed into packaging by the food business on site before being offered for sale to customers, cakes a baker puts in a box on their premises, and burgers or sausages prepacked by a butcher and sold on the same premises or market stall.

- Non-prepacked (loose) foods: foods that are sold ‘loose’ without any packaging, or are packed at the request of the consumer. For example, foods sold from a delicatessen (e.g., cold meats and cheeses), bread or pastries sold in bakery shops or a meal in a restaurant.

In December 2014, the EU Food Information to Consumers (FIC) Regulation and Food Information Regulations (FIR) made it a legal requirement for UK Food Business Operators (FBOs) to provide information on the 14 regulated allergens for non-prepacked (loose) foods including those sold as PPDS. This legislation states that FBOs can provide this information in written or verbal form, whereas for prepacked food, allergens have to be provided in written format.

In 2016, Natasha Ednan-Laperouse died after suffering an allergic reaction to sesame whilst eating a baguette. This was a PPDS food and triggered a major campaign for the legal requirements on PPDS to be tightened, given previous legislation did not specify that PPDS food required labelling. This new legislation was laid in England 2019, with Northern Ireland, Wales following suit in 2020 and Scotland in 2021, with the law across all countries coming into force on 1 October 2021. This new legislation is often referred to as ‘Natasha’s Law’ and requires PPDS foods to be labelled with the name of the food and a full ingredients list with allergens emphasised within the list (e.g. in bold).

In terms of responsibility, FBOs have an obligation to ensure that they are abiding by laws relating to the provision of allergen information across all food types, with Local Authorities (LAs) supporting and enforcing compliance with the legislation.

Research objectives

The FSA and FSS commissioned research to evaluate the implementation of the new PPDS legislation and the effect it has had on the three key audiences: consumers who have a food hypersensitivity (FHS consumers) across England, Northern Ireland and Wales and FBOs and Local Authorities (LA) across all four nations (footnote 1).

In particular, the research aimed to understand:

- Awareness of new requirements across FHS consumers, FBOs and LAs

- Uptake and compliance with the new requirements, including changes in business behaviour with regards to the types of foods they sell

- The effect of PPDS legislation on FHS consumers

- LA experience of resources to support compliance provided by the FSA and FSS and those offered and developed by LAs, and to understand whether additional support and resources are required

- What critical success factors and lessons learned can be gained from the implementation of PPDS which could be applied in future

Throughout this report, findings from previous research related to allergen labelling will be referenced where appropriate to further understand any potential changes due to the introduction of the new legislation. These previous research projects include a 2020 baseline telephone survey with FBOs (footnote 2), Food Sensitivities Survey with FHS consumers in 2021 (footnote 3) and research with LAs conducted internally by the FSA between April and May 2022.

Methodology

A mixed-method approach was undertaken for all audiences included in the research, with quantitative surveys followed by in-depth qualitative interviews. An overview of the methodology and completed interviews is shown in Figure 2.1. The specific details of the methodology are covered in Chapter 3.3.

Figure 1 - overview of methodology

Analysis and reporting

Quantitative analysis

Once fieldwork was complete, a set of data tables was produced for each of the audiences which encompassed all questions and contained breaks for key subgroups to allow for analysis of potential significant differences by these groups.

All differences noted between sub-groups are statistically significant to a 95% confidence level: by convention, this is the statistical ‘cut off point’ used to mean a difference is large enough to be treated as genuine. This means the significant differences noted throughout this report have a 95% chance of being ‘true’ (i.e. due to a genuine difference in the groups being compared, and only a 5% chance that the results are due to chance). In some cases, the report refers to a subgroup being ‘more’ or ‘less’ likely than average, this means that this subgroup is significantly different to the average, excluding the subgroup in question.

Where possible, comparisons have been made to surveys conducted prior to this research. Where comparisons are made and a difference is highlighted, this is also significant to a 95% confidence level.

The majority of the quantitative findings are reported as percentages, however, where the overall base size is lower than 50, these findings are reported using numbers.

Qualitative analysis

Findings from qualitative interviews businesses are integrated throughout. All interviews were written up into an analysis framework, which were structured under headings relating to the objectives, allowing discussions to be compared and judgements made about the commonality of experiences. The framework also allowed identification of any trends by different subgroups. An analysis session was then conducted to discuss initial interpretation of the findings and compare the emerging narratives to understand the key messages from the interviews.

It should be noted that findings from qualitative fieldwork provide insight into perceptions, feelings, and behaviours rather than quantifiable findings from a statistically representative sample. Because qualitative samples are small and purposively designed, the findings cannot be considered representative of the views of all stakeholders.

-

Food Standard Scotland did not partake in the consumer research because they are conducting their own research with FHS consumers in Scotland which will be reported separately.

-

The Food Industry’s Provision of Allergen Information to Consumers

Methodology overview

In order to develop a full picture of the awareness, understanding and impact of new PPDS labelling requirements, the research focused on three groups of stakeholders:

- Consumers in England, Northern Ireland and Wales who have at least one existing food hypersensitivity or a child with a food hypersensitivity

- FBOs with up to 249 employees across the UK

- LAs responsible for enforcing food safety regulations across the UK

A mixed-method approach to the research was adopted:

- Firstly, individuals from the three target groups were invited to complete surveys. Each group received a different survey that was specific to their engagement with PPDS labelling requirements.

- Secondly, some of those who took part in the surveys were then invited to take part in an in-depth interview to expand upon the information they gave in the survey. Again, there were three different topic guides used to structure interviews, which were designed to capture the nuances of each group’s experience.

The details of engagement with each group are shown in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1 Summary of methodology and completed interviews

| Method | Overview |

|---|---|

| Online survey with consumers |

|

| Qualitative interviews with consumers |

|

| Telephone survey of Food Business Operators (FBOs) |

|

| Online survey with LAs |

|

| Qualitative interviews with FBOs, Market Traders and LAs |

|

Consumers

Methodology

A total of 1,809 consumers with food hypersensitivities, or with a child with a food hypersensitivity, residing in England, Wales and Northern Ireland completed the online survey between 29 November 2022 and 13 January 2023. Consumers were approached through a range of sources:

- An external panel provider, which recruited 400 consumers who completed the survey.

- Three food hypersensitivity charities (Coeliac UK, Allergy UK and The Natasha Allergy Research Foundation), who shared an open link to the survey on social media and their newsletters.

- The FSA, who shared an open link to the survey on their social media towards the end of fieldwork with a specific aim to boost response rates in Wales and Northern Ireland.

The survey was approximately 15 minutes long and encompassed a number of topic areas: the nature of consumers’ food hypersensitivity; their use and confidence in food labels (both generally and specifically regarding PPDS foods); their awareness of new labelling requirements; their experience of buying PPDS foods since the introduction of the legislation; and the impact it has had for them. In the cases where the consumer had a child with a food hypersensitivity, the same topic areas were covered but framed in regards to their experience of purchasing PPDS foods for their child.

Consumers who completed the survey via an open link from a charity and the FSA indicated at the end of the survey whether they would be happy to be recontacted for a follow-up interview. A total of 659 consumers agreed to be recontacted, representing 53% of those asked.

A total of 31 consumers took part in a follow-up in-depth telephone interview, which explored their experiences in more detail. Broad targets were set to ensure the perspectives of a variety of consumers were captured; by country, severity of allergy, whether or not they had coeliac disease and whether they had a food hypersensitivity or their child did. In addition, a spread of awareness of legislation, PPDS purchasing behaviour and potential impact of the legislation were targeted. These interviews took place between 19 December 2022 and 11 January 2023, and lasted 45-60 minutes.

Sample profile

The FSA were keen to understand the perspective of consumers with their own hypersensitivity, and the experiences of those who have a child with a food hypersensitivity. Almost three quarters (74%) of consumers who completed the survey indicated they had a food hypersensitivity and around one in ten (11%) of all respondents stated that their child had a food hypersensitivity. A further 15% indicated that both they and their child had food hypersensitivities; this latter group responded to the survey regarding their own experience, rather than that of their child.

The severity of food hypersensitivity varied; over half of consumers (56%) stated that their food hypersensitivity was severe. Around a third (34%) indicated theirs was moderate and 8% felt theirs was mild. This rating related to the allergy or intolerance they felt to be the most severe if they had multiple allergies. Two in five (42%) consumers in the survey reported having multiple allergies.

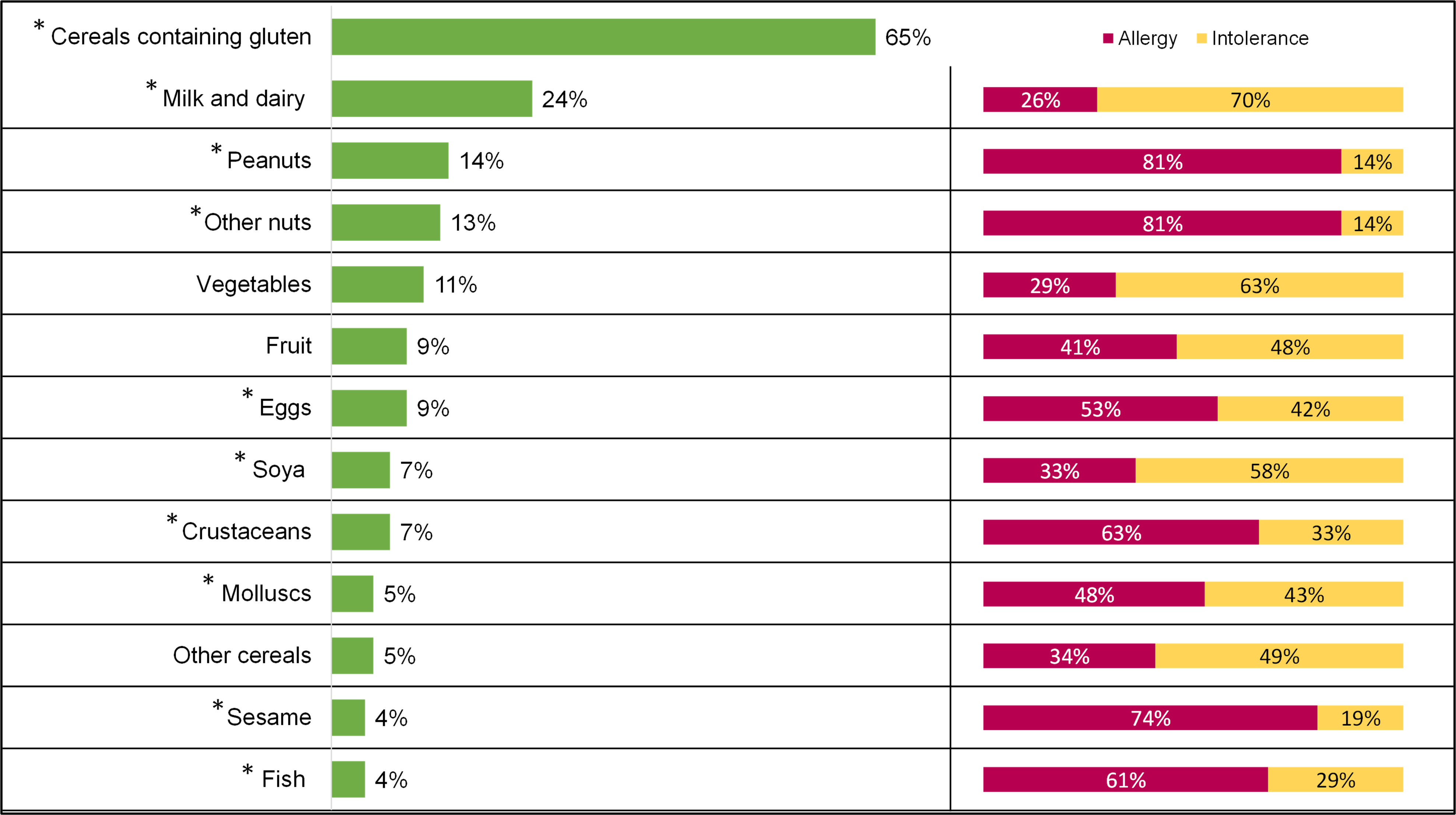

Overall, three-quarters (73%) of consumers had an allergy or intolerance to a regulated allergen only, with a further 19% having an allergy or intolerance to both a regulated and non-regulated allergen. The food which consumers had an allergy or intolerance to varied, with the most common being cereals containing gluten (65%). Almost half (46%) of surveys completed were obtained from Coeliac UK, which is likely to contribute to this prevalence. Of consumers who stated they had a food hypersensitivity to cereals containing gluten, 83% had Coeliac disease. 78% of those who had Coeliac disease said this was medically diagnosed. Taking this as a proportion of all consumers who took part, around half (53%) had Coeliac disease. Only around 1% of the population in the UK have Coeliac disease. (footnote 1) To help understand the impact of this on the findings, we have highlighted differences between those with and without Coeliac disease throughout the report.

Those who had a food hypersensitivity to cereals containing gluten, but were not diagnosed with Coeliac disease, more often referred to this as a food intolerance (72%) rather than an allergy (22%). Other food types with prevalent allergies and intolerances included milk and dairy (24%), peanuts (14%), other nuts (13%) and vegetables (11%). This is further detailed in Figure 3.2, which also shows whether this was classified by consumers as an allergy or intolerance. Food marked with an ‘*’ indicates a regulated allergen.

Figure 3.2 Food hypersensitivity and whether it is categorised as an allergy or intolerance (footnote 2)

A2. Do you / your child experience a bad or unpleasant reaction to any of the following foods? Base: All consumers (1,809). A4. How would you best describe your problem with this food? Base: All consumers who have a food sensitivity to each of the food types (milk and dairy (424), peanuts (253), other nuts (227), vegetables (104), fruit (144), eggs (163), soya (122), crustaceans (120), molluscs (99), other cereals (94), sesame (74), fish (66)).

Consumers were more likely to be intolerant, rather than allergic, to certain food types - particularly to milk and dairy (70% intolerance vs 26% allergy), vegetables (63% intolerance vs 29% allergy) and soya (58% intolerance vs 33% allergy). Conversely, consumers were more likely to report having an allergy, rather than an intolerance, to peanuts (81% allergy vs 14% intolerance), other nuts (81% allergy vs 14% intolerance) and sesame (74% allergy vs 19% intolerance).

In terms of demographics, the majority of consumers identified as female (79% vs 20% male) and White (95%). (footnote 3) The age of consumers varied; 14% were aged between 18 and 34 years old, 60% between 35 and 64 and 23% were 65 or older. The majority of consumers (85%) were in England, 9% in Wales and 6% Northern Ireland. (footnote 4)

When responding on behalf of their child with a food hypersensitivity, around half (47%) stated that their child was female, and a similar proportion (52%) had a male child with a food hypersensitivity . The age of the child varied, with 29% between 0 and 6 years old, 26% between 7 and 10 years old and 43% between 11 and 17 years old.

Qualitative interviews

A total of 31 in-depth interviews were achieved with a subset of the consumers who completed the survey. Interviews were conducted with a variety of consumers, targeted to ensure a range of people by country, whether they or their child had a food hypersensitivity, the nature and type of food hypersensitivity and experiences since the new legislation. Tables 3.2 to 3.10 show the number of consumers who took part in the qualitative interviews by subgroup.

Table 3.2 Qualitative interviews by country

| Country | Number of achieved qualitative interviews |

|---|---|

| England | 25 |

| Northern Ireland | 3 |

| Wales | 3 |

| Total | 31 |

Table 3.3 Qualitative interviews by respondent or child's food hypersensitivity

| Respondent or child’s food hypersensitivity | Number of achieved qualitative interviews |

|---|---|

| Respondent has food hypersensitivity | 24 |

| Child has food hypersensitivity | 7 |

| Total | 31 |

Table 3.4 Qualitative interviews by severity of food hypersensitivity

| Severity of food hypersensitivity | Number of achieved qualitative interviews |

|---|---|

| Mild | 3 |

| Moderate | 5 |

| Severe | 21 |

| Don't know | 2 |

| Total | 31 |

Table 3.5 Qualitative interviews by coeliac disease status

| Coeliac disease status | Number of achieved qualitative interviews |

|---|---|

| Coeliac disease | 16 |

| Not Coeliac disease | 15 |

| Total | 31 |

Table 3.6 Qualitative interviews by awareness of PPDS labelling requirements

| Awareness of PPDS labelling requirements | Number of achieved qualitative interviews |

|---|---|

| Aware of PPDS labelling requirements before survey | 28 |

| Unaware of PPDS labelling requirements before survey | 3 |

| Total | 31 |

Table 3.7 Qualitative interviews by change in experience of buying PPDS foods since October 2021

| Change in experience of buying PPDS foods since October 2021 | Number of achieved qualitative interviews |

|---|---|

| Experience of buying PPDS has improved since Oct 21 | 12 |

| Experience of buying PPDS has worsened since Oct 21 | 2 |

| Total | 14 |

Table 3.8 Qualitative interviews by change in quality of life since October 2021

| Change in quality of life since October 2021 | Number of achieved qualitative interviews |

|---|---|

| Quality of life has improved since Oct 21 | 11 |

| Quality of life has worsened since Oct 21 | 4 |

| Total | 15 |

Table 3.9 Qualitative interviews by change in amount of PPDS food purchases since October 2021

| Change in amount of PPDS food purchases since October 2021 | Number of achieved qualitative interviews |

|---|---|

| Buys PPDS foods more since Oct 21 | 9 |

| Buys PPDS foods less since Oct 21 | 9 |

| Total | 18 |

Table 3.10 Qualitative interviews by change in confidence in buying PPDS foods since October 2021

| Change in confidence in buying PPDS foods since October 2021 | Number of achieved qualitative interviews |

|---|---|

| Confidence in PPDS labelling increased since Oct 21 | 12 |

| Confidence in PPDS labelling not increased since Oct 21 | 7 |

| Total | 19 |

Food Business Operators

Methodology

A total of 900 food business operators (FBOs) in the UK completed the telephone survey between 25 November 2022 and 12 January 2023. The sample was obtained through an external provider (Market Location) and during fieldwork, interviews were monitored by business size, sector and country to ensure the sample size for each group was sufficient and a representative sample was achieved. (footnote 5)

The survey took an average of 19 minutes to complete and were conducted with the person with responsibility for food safety at the FBO. The survey covered awareness and understanding of PPDS, current PPDS practices, support with and effects of PPDS legislation, as well as key firmographics about the business.

During analysis, the data was weighted to match the profile of the population by sector, size and country. (footnote 6)

At the end of the survey, 449 FBOs agreed that they were happy to take part in a follow-up qualitative interview, representing 50% of the sample. As with the consumer interviews, targets were set in order to achieve a broad range of perspectives, in this case, these were centred around country, size and sector, as well as awareness of, compliance with PPDS legislation and perceived ease of this. A total of 19 FBOs took part in in-depth interviews between 17 December 2022 and 3 February 2023. These were completed over the phone or via Zoom or Microsoft Teams. Interviews took between 45 and 60 minutes.

In order to account for those who sell PPDS foods from a market stall, five businesses that sold PPDS food from a moveable or temporary premises (e.g. a market stall or mobile sales vehicle) also took part in a qualitative interview. Once they had agreed to participate, market traders took part in an interview over the phone or via Zoom or Microsoft Teams. These interviews took place between 16 January and 1 February 2023 and took between 45 and 60 minutes.

Profile of FBOs

FBOs that are restaurants or cafes makes up the largest proportion (49%) of businesses that took part in the survey, followed by general retail (28%) and catering (15%). Half (50%) were the smallest business size with between 1 and 5 employees, and the majority (84%) were situated in England. A full breakdown of interviews achieved by country, size and sector is shown in Tables 3.11 to 3.14.

The proportion of surveyed businesses in each size and sector also represent the relevant proportions within each of the nations.

The majority (91%) of businesses sold PPDS foods at the time they participated in the survey. The remaining 9% had sold PPDS foods in the previous 12 months but had stopped doing so at the time of the survey. (footnote 7)

Table 3.11 Breakdown of businesses by country

| Country | Number of achieved mainstage surveys |

|---|---|

| England | 612 |

| Northern Ireland | 52 |

| Scotland | 161 |

| Wales | 75 |

| Total | 900 |

Table 3.12 Breakdown of businesses by number of employees

| Number of employees | Number of achieved mainstage surveys |

|---|---|

| Between 1 and 5 employees | 347 |

| Between 6 and 10 employees | 266 |

| 11 or more employees | 287 |

| Total | 900 |

Table 3.13 Breakdown of businesses by sector group

| Sector group | Number of achieved mainstage surveys |

|---|---|

| Catering | 355 |

| Retail | 545 |

| Total | 900 |

Table 3.14 Breakdown of businesses by sector (detailed)

| Sector detailed | Number of achieved mainstage surveys |

|---|---|

| Caterers | 107 |

| Restaurants and cafes | 248 |

| Bakers | 136 |

| Butchers | 133 |

| Delicatessens | 79 |

| General retail | 197 |

| Total | 900 |

Qualitative interviews

In terms of the qualitative interviews, 19 FBOs including five businesses that sold PPDS food from a moveable or temporary premises (e.g. a market stall or mobile sales vehicle) who completed a qualitative interview. The profile is shown in Tables 3.15 to 3.18.

Table 3.15 Breakdown of FBO qualitative interviews by country

| Country | Number of achieved mainstage surveys |

|---|---|

| England | 12 |

| Northern Ireland | 2 |

| Scotland | 4 |

| Wales | 1 |

| Total | 19 |

Table 3.16 Breakdown of FBO qualitative interviews by number of employees

| Number of employees | Number of achieved mainstage surveys |

|---|---|

| Between 1 and 5 employees | 8 |

| Between 6 and 10 employees | 5 |

| 11 or more employees | 6 |

| Total | 19 |

Table 3.17 Breakdown of FBO qualitative interviews by sector group

| Sector group | Number of achieved mainstage surveys |

|---|---|

| Catering | 9 |

| Retail | 10 |

| Total | 19 |

Table 3.18 Breakdown of FBO qualitative interviews by sector (detailed)

| Sector detailed | Number of achieved mainstage surveys |

|---|---|

| Caterers | 5 |

| Restaurants and cafes | 4 |

| Bakers | 5 |

| Butchers | 2 |

| Delicatessen | 2 |

| General retail | 1 |

| Total | 19 |

Local Authorities

Methodology

A total of 126 staff members, covering 124, of the 398 Local Authorities (LAs) across the UK, completed the online survey between 1 December 2022 and 13 January 2023. (footnote 8) The FSA and FSS distributed the link to the online survey by email and followed up to encourage LAs to complete the survey if they had not done so already. Upon invitation to take part in the survey, the email asked that the person best placed within the local authority to provide feedback on the experience of the PPDS labelling requirements takes part. This may be their lead food officer or someone they nominate to take part. (footnote 9) The survey covered their understanding of PPDS, how PPDS checks are carried out, experience of these checks and enforcement and impact on LAs and FBOs in their area.

A total of 39 LAs agreed to be recontacted in the survey, of these, 21 took part in an interview over the phone or via Zoom or Microsoft Teams between 14 December 2022 and 26 January 2023. These interviews lasted between 45 and 60 minutes on average.

Profile of LAs

In line with the UK profile of LAs, the majority of who completed the survey were in England. A full breakdown by country is shown in Table 3.19.

Table 3.19 Profile of LAs who took part in survey by country

| Country | Number of achieved mainstage surveys | Total number of LAs in each country |

|---|---|---|

| England | 82 | 333 |

| Northern Ireland | 11 | 11 |

| Scotland | 19 | 32 |

| Wales | 12 | 22 |

| Total | 124 | 398 |

Staff members who completed the survey indicated the area of the LA that they worked in, most worked in food standards or safety (80%), others worked in environmental health (28%) and trading standards (16%). (footnote 10)

Qualitative interviews

The profile of LAs who took part in the qualitative interviews by country, ease of checking compliance and overall description of the level of compliance of FBOs in their area with PPDS labelling requirements is shown in Tables 3.20 to 3.23.

Table 3.20 Profile of LAs who took part in qualitative interviews by country

| Country | Number of achieved qualitative interviews |

|---|---|

| England | 12 |

| Northern Ireland | 1 |

| Scotland | 7 |

| Wales | 1 |

| Total | 21 |

Table 3.21 Profile of LAs who took part in qualitative interviews by experience of compliance checks

| Experience of compliance checks | Number of achieved qualitative interviews |

|---|---|

| Found compliance checks easy | 11 |

| Found compliance checks difficult | 10 |

| Total | 21 |

Table 3.22 Profile of LAs who took part in qualitative interviews by perceived level of compliance in area

| Perceived level of compliance in area | Number of achieved qualitative interviews |

|---|---|

| Overall level of compliance good | 9 |

| Overall level of compliance poor | 10 |

| Total | 21 |

Table 3.23 Profile of LAs who took part in qualitative interviews by perceived experience of Food Business Operators

| Perceived experience of FBOs | Number of achieved qualitative interviews |

|---|---|

| FBO experience of compliance considered easy | 1 |

| FBO experience of compliance considered difficult | 20 |

| Total | 21 |

-

Cereals containing gluten is excluded from classification of allergy and intolerance due to the majority having Coeliac disease specifically.

-

This is broadly in line with the demographic make-up of those who took part in the Food Sensitivity Study: Wave Two (76% were female and 23% male). The majority (86%) were from a White background in this survey as well, and the age range also followed a similar pattern.

-

Consumers in Scotland were out of scope of the research.

-

FBOs with over 250 employees were excluded from the research as the FSA and FSS wished to engage micro and small businesses as they made up the largest part of the market.

-

This was based on figures published on ‘Nomis’, a service provided by the Office of National Statistics (ONS), of the official census and labour market statistics.

-

The latter were included in the survey to understand how or if the new labelling requirements impacted their behaviour regarding PPDS.

-

In two LAs, two staff members took part in the survey. The methodology involved the survey being sent out to LAs as an open link, meaning it could be accessed by multiple staff at the local authority, leading to these multiple completions.

-

In a small minority of cases, the person confirmed they had the knowledge or oversight of PPDS labelling requirements but were not directly involved in compliance checks.

-

Some LA staff members worked across more than one of these areas.

Consumers

Awareness and understanding of PPDS foods

Around a quarter (26%) of consumers were aware of the term PPDS before they took part in the survey. There were no statistically significant differences by country in the proportion aware (England: 26%; Northern Ireland: 29%; Wales: 30%). However, there were differences by age and the nature of food hypersensitivity.

Awareness levels were generally higher among younger consumers: those aged between 18 and 34 were more likely than those aged 65 or older to be aware of the term PPDS (35% vs 17%). With regards to food hypersensitivities, those with an allergy other than Coeliac disease were more likely to be aware of the term PPDS, prior to taking part in the survey, than those with Coeliac disease (31% vs 22%). Those who reported both themselves and their child having a food hypersensitivity and those reporting just their child having a food hypersensitivity were both more likely to have heard of the term before compared with those reporting just themselves with a food hypersensitivity (38% and 32% respectively vs 23%).

Interviews with consumers highlighted that they typically became aware of the term PPDS through a food hypersensitivity charity or from media coverage of Natasha Ednan-Laperouse’s death. Some stated they became aware after they or someone close to them was diagnosed with a food hypersensitivity.

“I followed Natasha's Law. Her parents have an Instagram page that they run and I follow that and it was on there [the term PPDS].”

Consumer, Northern Ireland, Severe hypersensitivity

"[I became aware of PPDS] Quite quickly after [my child] was diagnosed [with coeliac disease] a year ago."

Consumer, Wales, Severe hypersensitivity

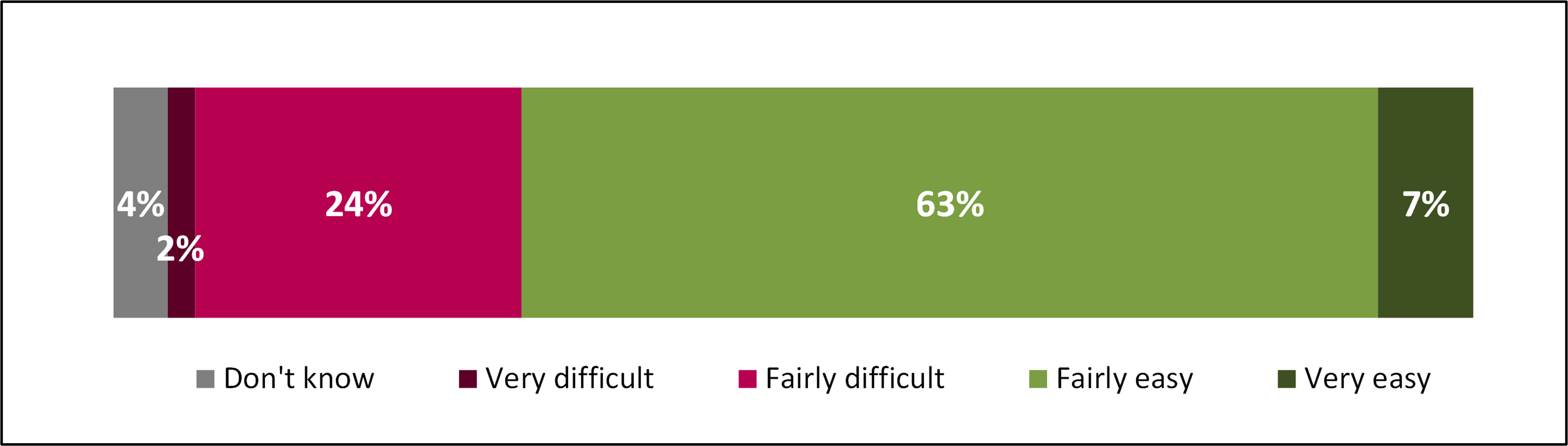

After the survey captured awareness levels, the term was defined and explained to consumers as follows: 'Pre-packed for direct sale (PPDS) foods are packed on the same premises as they are being sold to consumers and where the food is packed before being offered for sale to customers’. Following this, consumers were asked to what extent it would be easy or difficult to identify such food. As shown in Figure 4.1, around half (52%) of consumers said that it would be difficult for them to identify if food was packaged on site and therefore whether it would classify as PPDS (with 22% reporting that it would be very difficult).

Figure 4.1 Extent to which consumers found identifying whether food was packaged on site easy or difficult

C2. If you entered a food business, how easy or difficult would it be to identify whether food was packaged on site? Base: All consumers (1809)

There were again no statistically significant differences by country in the proportion who found it difficult to identify whether food was packaged on site (England: 53%; Northern Ireland: 50%; Wales: 51%). However, those in Northern Ireland were more likely to find it easy than average (26% vs 19% overall).

The likelihood of reporting difficulty with identifying PPDS foods increased with age and food hypersensitivity severity. Those aged 18 to 34 perceived it to be easier than both those aged 35 to 64 and those aged 65 or older (32% vs 19% and 10% respectively).Those with a mild allergy or intolerance were more likely than those with either a moderate and severe allergy to find it easy (31% vs 21% and 16% respectively), while those with a moderate or severe allergy or intolerance were more likely to find it difficult (49% and 57% vs 52%). Those also reporting both themselves and their child having a food hypersensitivity were more likely than those reporting just themselves or just their child having a food hypersensitivity to perceive it to be easier (28% vs 17% and 19% respectively).

During qualitative interviews, some said it would be difficult for them to identify if food was packaged on site, because PPDS foods were often placed alongside other prepacked food. Others said it could be harder to determine when printed labels and branded packaging is used, cited as more common in larger outlets, as this packaging can mirror the appearance of non PPDS foods.

“[Supermarkets] have cold meat in the deli in packaging, and I am unsure whether they package it centrally or in-store.”

Consumer, Wales, Moderate hypersensitivity

“In larger stores [identifying PPDS] it is quite difficult; in local outlets it would be quite easy.”

Consumer, England, Severe hypersensitivity

Awareness and understanding of PPDS labelling requirements

The PPDS labelling requirements were defined and explained within the survey ahead of questions around awareness of them. Once defined, the vast majority (87%) reported having heard of PPDS labelling requirements, although only a small proportion (18%) knew a lot about it, as shown in Figure 4.2.

Figure 4.2 Consumer awareness of new PPDS labelling requirements

D1. Before today, to what extent were you aware of the new PPDS food labelling requirements, or Natasha’s Law? Base: All consumers (1809)

Awareness of PPDS labelling requirements was broadly similar across the three countries (England: 88%; Northern Ireland: 84%; Wales: 88%). However, those with Coeliac disease were more likely than those with another food hypersensitivity (91% vs 83%) and those with an allergy to a regulated allergen were more likely those with only an allergy to a non-regulated allergen (89% vs 76%) to have heard of the new requirements, regardless of understanding.

Parents who reported having a child with a food hypersensitivity and those reporting both themselves and their child having a food hypersensitivity were both more likely than those reporting just themselves having a food hypersensitivity to have heard of the new labelling requirements and knowing quite a lot about it (23% and 25% respectively vs 15%). Similarly, those with a severe allergy were more likely to report having heard of the new labelling requirements and knowing quite a lot about it than those with a mild or moderate allergy (21% vs 10% and 15% respectively).

Consumers typically first heard of the new PPDS labelling requirements from traditional media sources. As shown in Figure 4.3, half (50%) of consumers became aware via local or national newspapers or TV, followed by 30% who learned of the requirements from a registered charity, and 19% via social media.

Figure 4.3 How consumers became aware of the new labelling requirements

D2. How did you hear about the new PPDS food labelling requirements? Base: All consumers who were aware of the new labelling requirements (1582).

Across the three countries, traditional media, local or national newspaper or TV, was the top source of awareness (England: 51%; Northern Ireland: 42%; Wales: 37%). In England this was followed by registered charities (30%) and in Northern Ireland and Wales social media (41% and 30% respectively).

There were some differences by age with those aged 65 or older were more likely to have become aware of the new labelling requirements through local or national newspaper or TV than those aged 18 to 34 and those aged 35 to 64 (60% vs 34% and 49% respectively). Additionally, those aged 18 to 34 and those aged 35 to 64 were both more likely to have become aware through social media or the FSA’s website than both those aged 65 or older (social media: 33% and 21% vs 8%; FSA website: 17% and 9% vs 5%).

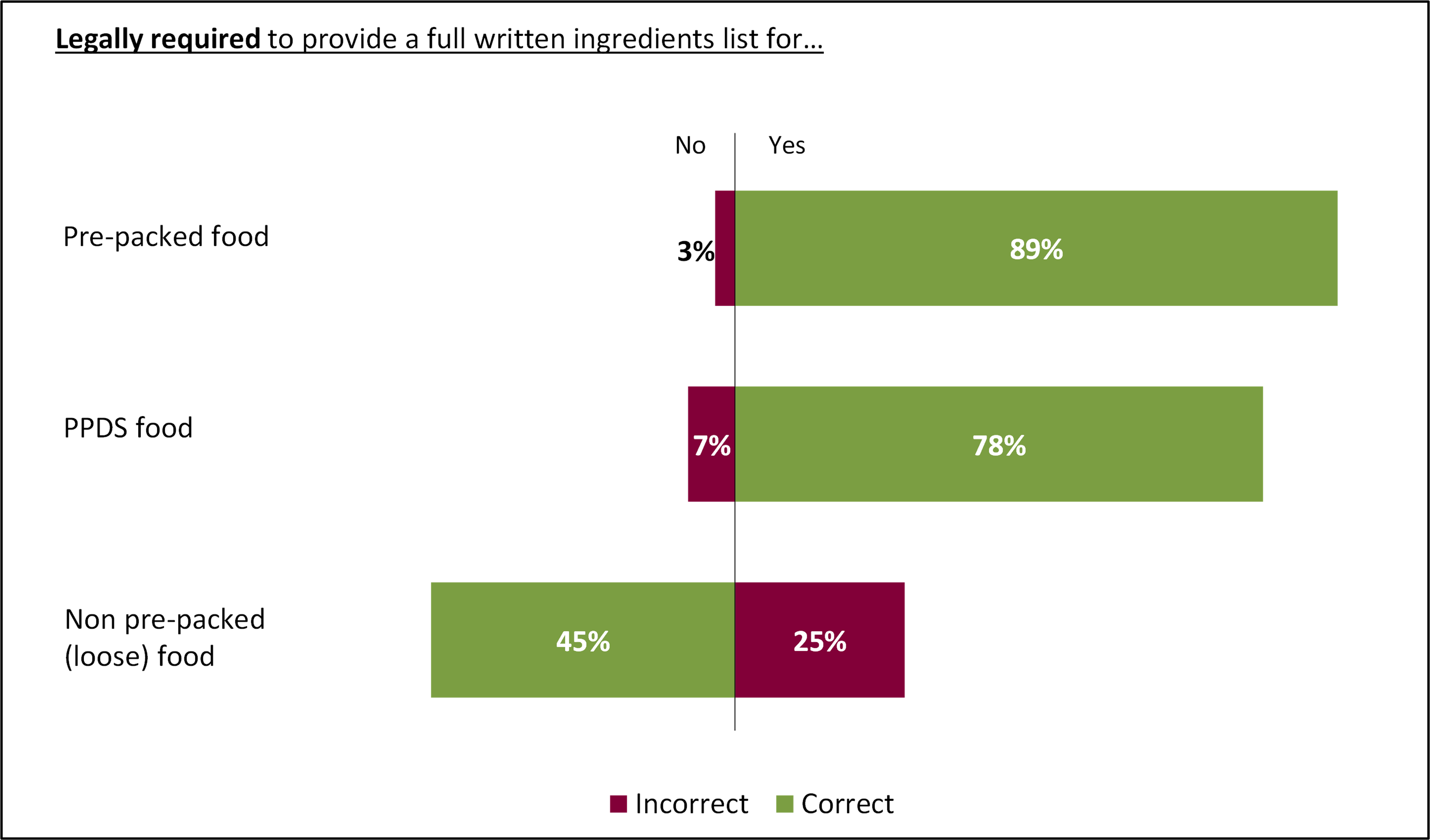

In addition to being asked about their awareness of PPDS labelling requirements, consumers were also asked which types of food they thought FBOs were legally required to provide written full ingredient lists for. The majority correctly identified that there is a legal requirement for written full ingredients lists to be provided on prepacked food (89%) and PPDS foods (78%) as shown in Figure 4.4. However a quarter (25%) incorrectly thought this was also a legal requirement for non-prepacked food, with less than half (45%) correctly identifying it was not.

Figure 4.4 Awareness of FBOs legal requirements for providing food information

B4. As far as you are aware, which of the following types of food are businesses legally required to provide written full ingredient lists for? Base: All consumers (1809).

Across these three food types, a third (32%) of consumers were aware of the legal requirements for providing food information for all three categories (prepacked food, PPDS food and non-prepacked (loose) food), 52% for any two categories, and only 5% were unaware for all 3 foods. Consumers in Northern Ireland and those aged 18 to 34 were both more likely than average to have selected all three statements correctly (44% and 39% vs 32%).

Consumers shared whether, in their view, PPDS foods only needed to be labelled with information about whether they contain any of the 14 specified allergens, rather than with a full ingredients list. As illustrated in Figure 4.5, two-thirds (67%) disagreed with this, in line with new PPDS requirements, and only around a fifth agreed (21%).

Figure 4.5 Consumers view on if PPDS only needed labelling if they contain an allergen

C8. 'In my view, foods prepacked for direct sale (PPDS) only need to be labelled with information about whether they contain any of the 14 specified allergens, rather than with a full ingredients list' Base: All consumers (1809).

By age, those aged between 35 to 64 were more likely to disagree than those aged 65 or older (69% vs 58%). Those with a regulated allergen were more likely than those with only a non-regulated allergen and those with both a regulated and non-regulated allergen to agree that PPDS foods only needed labelling if they contain any of the 14 specified allergens (22% vs 15% and 17%).

During qualitative interviews, many were aware of the new labelling requirements, their purpose, and its aim being to better protect and inform those with a food hypersensitivity when purchasing PPDS foods. Despite this, many struggled to define specifically what was required under the new labelling requirements.

This high-level awareness allowed many to provide a broad definition and those who had noticed changes in PPDS foods labelling were able to presume what the new legislation required from these changes.

"They've [FBOs] probably got legal requirements although I'm not quite sure what they are. You just assume and hope that companies are doing the legal requirement.”

Consumer, England, Severe hypersensitivity

“I've noticed the changes because packaging is very clear now, it's obvious you don't have to think, ‘Does it contain [allergens]?’ If you weren't sure, it is there written on the packaging for you.”

Consumer, England, Moderate hypersensitivity

Many agreed with the new legislation and believed all PPDS foods should have labels. There was also surprise amongst some that this has not always been a requirement for FBOs on PPDS foods.

"As there are less common allergies, it is important to have all ingredients on the packaging."

Consumer, England, Severe hypersensitivity

“I know they were trying to push for a law but the scary thing is that law only came into place because somebody died.”

Consumer, England, Severe hypersensitivity

Food Business Operators

Awareness and understanding of PPDS foods

Two-thirds (66%) of FBOs reported being aware of the term PPDS before participating in this research; with around a third (33%) having not heard of the term.

There were no statistically significant differences by country in terms of awareness of the term PPDS (England: 66%; Northern Ireland: 65%; Scotland: 69%; Wales: 63%). However, amongst those who currently sell PPDS foods there were differences by sector. Both butchers and delicatessens were more likely to be aware of the term PPDS, prior to this survey (79% and 80% vs 66% overall).

After the survey captured awareness levels of the term PPDS, the term was defined and explained to FBOs as: Pre-packed for direct sale (PPDS) foods that is packed before being offered for sale by the same food business to the final consumer, where this takes place on the same premises or location; or from moveable or temporary premises such as a market stall or mobile sales vehicle, before asking to what extent six particular aspects of the PPDS definition were clear to them. As shown in Figure 4.6, FBOs reported that they felt the PPDS definition – across all aspects – was clear, with four fifths clear about each aspect (80%), ranging from 94% of FBOs who felt the definition of packaging was clear, to 82% of FBOs who felt it was clear which of their premises constitute part of the same food business. However, a fifth (20%) were unclear on at least one aspect.

Figure 4.6 FBOs: aspects of the PPDS definition considered clear

A4. To what extent, if at all, are the following aspects of the definition of PPDS clear to you? Base: All FBOs (900). *NB FBO’s were only asked this statement if they had multi-site establishments (394).

Amongst those who sold PPDS foods at the time of the survey, butchers and general retail were more likely than average to be clear on all aspects of the definition (88% and 86% respectively). (footnote 1) In contrast, catering venues who sold PPDS foods were less likely to be clear on all aspects of the definition than those who sell PPDS foods (72%).

Awareness also varied by size; FBOs with 11 or more employees who sold PPDS were more likely to say they were clear on all aspects of the definition (88%) than smaller FBOs with between 1 and 5 employees (76%) and or between 6 and 10 employees (82%).

Reflecting the results of the survey, during qualitative interviews most FBOs said they had a good understanding of what constitutes PPDS food. However, some explained that they initially faced a steep learning curve as it was not a term that they had used internally prior to the PPDS labelling requirements being announced.

“I initially thought they're not pre-packaged. You have to look at it from the customer not from you as the supplier. From a customer's perspective yes, it's a PPDS product.”

FBO, England, Catering, 11 or more employees

Some FBOs explained that they occasionally encountered confusion about the definition of PPDS. For example, the owner of a mobile food business said that they were unclear whether pre-ordered meals for collection counted as PPDS while a butcher was uncertain whether products packaged at an offsite kitchen met the definition of PPDS.

“The confusing thing for us is sometimes there will be people that ring up and say, ‘right we want four vegetarian meals and four meat dinners, we’re coming at four to pick it up’. We feel like we're in a bit of a limbo with that.”

FBO, England, Catering, 11 or more employees

“Butchery products are prepared onsite but everything else is prepared offsite and I’m not sure if they actually count as PPDS.”

FBO, England, Delicatessen, 11 or more employees

Awareness and understanding of PPDS labelling requirements

Most FBOs (91%) were aware of the PPDS labelling requirements before taking part in the research, with few (8%) reporting they were unaware.

There were no statistically significant differences by country in terms of awareness of the PPDS labelling requirements before taking part in the research (England: 90%; Northern Ireland: 94%; Scotland: 91%; Wales: 88%).

Amongst those who sold PPDS foods currently there were differences in awareness by sector and size. Catering and general retail FBOs were more likely than average to report being aware of the legal requirements to label PPDS foods (96% and 95% respectively). Conversely restaurants and cafes were less likely than average to state they were aware (83% vs 91%). With regards to size, FBOs with 11 or more employees, who currently sold PPDS, were almost wholly aware of the labelling requirements and as a result more likely be aware than average (97% vs 91%). Those with between 1 and 5 employees and those with between 6 and 10 employees were less aware than those with 11 or more employees (87% and 90% vs 97%).

During qualitative interviews, most FBOs demonstrated good awareness and understanding of PPDS labelling requirements. As with the definition of PPDS, many had experienced points of uncertainty and confusion to begin with, but these generally passed following the receipt of guidance or training. A few reported changing their practices around where confusion persisted.; for example, selling foods that were formally PPDS as loose foods. Further detail on such changes to practices is presented in Chapter 6.

“The biggest challenge was simply figuring out what had to go on the labels … It took a while to sort out, but it’s fine now.”

FBO, Scotland, Restaurant/café, 1 to 5 employees

“There was a grey area where we had sandwiches we had prepared, and we would wrap them in a wax wrap just to keep the sandwich together. Our consultant said that was too on the line, so we now sell it loose without any packaging to skirt around that.”

FBO, England, Retail, 11 or more employees

Most LAs that took part in qualitative interviews believed FBOs generally had good awareness and understanding of PPDS labelling requirements. However, some identified small independent FBOs and takeaways as an exception to this. These FBOs were said to have lower awareness and understanding of PPDS labelling requirements owing to them not having the time or dedicated staff to engage with food information regulations and, where English is not the first language of owners and staff, because guidance was difficult to understand.

“You might have a one-man band that doesn’t have the technical expertise or resource to help with it and he will probably do nothing until we come along and give advice.”

Local Authority, Scotland

“Sometimes, with a language barrier, explaining the PPDS labelling requirements can be even more difficult. They don’t understand it.”

Local Authority, England

Local Authorities

Awareness and understanding of PPDS foods