Chapter 4: Informing consumers, latest developments in food labelling and information

Every day, consumers are met with an abundance of information about the food they eat, whether on labels and packaging, websites, or other marketing and advertising materials.

At a glance:

In this chapter we look at:

- how food information regulations are evolving in the wake of the UK’s EU departure

- what impact these developments are having on the public and the food industry

- what factors may influence food information standards in the future

Introduction

Every day, consumers are met with an abundance of information about the food they eat, whether on labels and packaging, websites, or other marketing and advertising materials.

Much of this is designed to help us make objective and informed decisions about our food choices – and for some people this can have significant health implications, particularly for those who have food allergies or a diet affected by long-term conditions that affect their dietary needs.

Yet the clarity and accuracy of this information may conflict with how a product is actually being marketed or labelled. When this happens, food information standards are there to ensure food companies are truthful and transparent in what they say, and that consumers get the clear, accurate information they need.

This chapter explores the implications in this area now the UK has left the EU. Many of the rules governing food labelling and information in this country have their basis in European food law. Now that much of the UK falls outside this jurisdiction, we look at the steps that have been taken to maintain stability and continuity for businesses and what the future may hold.

We also look at how the standards for food labelling and information have developed in recent years, charting the impact of key changes such as improved allergen

information, front-of-pack nutrition labelling and calorie labelling on menus in restaurants and other out-of-home food establishments.

Finally, we show the results from a basket of foods survey, which sampled the safety and composition of a selection of items on sale in England and Wales, and the results of the FSS annual food sampling programme.

What information must be on a food label?

Food labelling must, by law, convey a number of important pieces of information.

The table below sets out the most common requirements for most packaged foods – there are some important exceptions which are explained more fully in the official guidance for businesses.

1. Name and description: All packaged food must accurately describe what the food is. Some food names must meet specific compositional standards which protect consumers by preventing ingredients being substituted by poorer quality alternatives. For example, a beef burger must contain at least 62%

beef in order to be described as such [32].

2. Ingredients list: The list of ingredients is the main place on the label where detailed information about what is in the food is found. Subject to exemptions, any food with two or more ingredients must list them all in descending order of weight. The list must clearly emphasise any of 14 main allergens contained in the product. If there are no specific compositional standards the quantity (for example a percentage) of certain ingredients must be given. The information must

be in the name or the list of ingredients to let consumers know how much they are getting. It applies in certain circumstances including when an ingredient is emphasised in words or pictures on the label, or to ingredients that the consumer associates with the food such as the cheese in a margherita pizza.

This label shows the name of the food along with an ingredients list which emphasises the allergens.

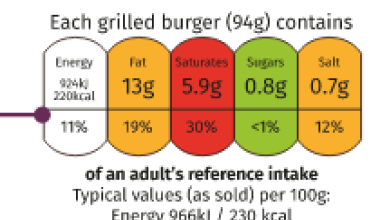

3. Nutritional information: Packaged food must state the amount of energy, total fat, saturated fat, carbohydrates, sugar, protein and salt in a typical portion.

A voluntary front-of-pack nutrition labelling scheme used by many food manufacturers also helps consumers to compare the calorie, fat, sugar and salt content of food products at a glance.

This is an example of a nutrition label, often referred to as mandatory back-of-pack nutrition information.

This is an example of a voluntary front-of-pack nutrition label. This is based on repeating some elements of the mandatory back-of-pack nutrition declaration to give consumers an at-a-glance indication of the energy and nutrient content.

4. Best before or use by date: Packaged food should include either a best before or use by date. Use by dates are on food that goes off quickly, such as meat products or ready-to-eat salads – it tells the consumer when the food will no longer be safe to eat. The best before date, sometimes shown as BBE (best before end), is about quality not safety. The food will be safe to eat after this date but may not be at its best quality. Both dates are only accurate if the storage information on the label is properly followed.

5. Warnings: Food containing certain additives or other ingredients must also contain relevant warnings – for example, any beverage not based on tea or coffee that contains caffeine above a certain amount must state, ‘Not suitable for children, pregnant women and persons sensitive to caffeine'.

6. Place of Origin: Some foods should also contain information about where the food is from (its place of origin). For certain foods, such as prepacked fresh and

frozen pork, poultry and fish, origin information is always needed. In the case of processed food, origin information is needed if the labelling suggests it may come

from a certain country or place when this is not the case. If origin information is given, the labelling needs to show where the key ingredients come from or if they

are different from the origin of the food as whole.

Example of a label which may give the impression that the food is from Greece.

Example of a label which shows a food made with an ingredient from another country.

Departmental responsibilities and enforcement

Responsibility for the policy on food labelling and composition standards sits with different departments across the UK.

In England, Defra has the responsibility for general food labelling and composition standards, with the FSA having responsibility for food safety labelling and the DHSC leading on nutrition labelling.

In Scotland, FSS has responsibility for general food labelling, including food safety labelling, compositional standards, and nutrition labelling.

In Wales, the FSA has responsibility for general and food safety labelling, with the Welsh Government having responsibility for nutrition labelling.

In Northern Ireland, the FSA has responsibility for all these areas.

Enforcement of these requirements is carried out by local authorities, and this may be the responsibility of environmental health or trading standards departments

depending on location in the UK.

The impact of our departure from the EU

EU Exit

While the majority of the food labelling and information laws originating from the EU have been retained, there are some changes affecting trade between Great Britain and the EU, and British businesses sending food to Northern Ireland. The FSA, FSS and government departments, including Defra and the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA) in Northern Ireland have helped industry with these changes.

The UK’s departure from the EU marks a significant turning point for food information laws, which have historically been heavily influenced by European regulations. From now, decisions on how to regulate and manage labelling and food information standards will be taken in Great Britain.

From a consumer’s point of view, this has had very little noticeable impact to date – the immediate focus has been on maintaining continuity with existing EU laws to minimise any disruption to supply. However, some important foundations for a post- EU approach to food information standards have been put in place:

Updating the law

Existing EU laws that govern food labels have now been converted into British laws, with corresponding changes to the domestic regulations in England, Scotland and Wales to allow enforcement authorities to continue enforcing these laws.

Removing the mutual recognition of food composition standards

“mutual recognition” arrangements for products containing meat, spreadable fats and wheat flour produced in the EU, Iceland, Norway and Turkey have been removed in Great Britain. Products such as lemon curd, mincemeat, sausage, and unfortified margarine and wheat flour had previously been allowed for sale in the UK even if they did not meet UK compositional standards, provided they had been sold legally in their country of origin. From 1 October 2022, this will no longer be the case. This means, for example, imported flour must now be fortified with calcium, iron, thiamin and niacin to the level required for British milled flour.

Changes to address and country of origin labelling

The UK's EU departure will also mean changes to address labelling and country of origin labelling for businesses trading in Great Britain. Businesses have been given until the end of September 2022 to make necessary changes. From 1 October 2022, those businesses not established in Great Britain will need to either use importers or set up legal entities in this country.

New powers to assess and authorise nutrition and health claims

Great Britain now has responsibility for assessing and authorising the nutrition and health claims made by products. A new UK Nutrition and Health Claims Committee (UKNHCC) has been established to provide expert advice and scrutiny to support these decisions.

Other key developments in food information standards

Information on food labels should help us make safe and informed choices about what we eat, and is particularly important in helping people with food allergies and hypersensitivities to stay safe.

While it seems unlikely that the measures above have had any short-term impact on food information standards, some of the following major policy changes – and

several more pending – will have a significant impact on the way consumers are given information about what they eat.

Changes to labelling laws for prepacked foods for direct sale

New regulations to amend the Food Information Regulations 2014 (and equivalents in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales)33, also known as ‘Natasha’s Law’, were introduced across the UK from 1 October 2021. All food sold prepacked for direct sale (PPDS) must now be labelled with the name of the food and a list of all ingredients, with any of the 14 major allergens emphasised within that list. The requirements cover all foods that are packed on the same premises from which they are sold.

The change was inspired by a campaign led by the family of Natasha Ednan‑Laperouse, who suffered a fatal allergic reaction to a shop-bought baguette containing sesame.

Example of a label used for food sold prepacked for direct sale.

Mandatory calorie information for eating out in England

In April 2022, new regulations came into effect in England requiring calorie information to be provided for food sold outside the home by restaurant chains and other large businesses of over 250 employees. The measure forms part of the UK Government’s Obesity Strategy and is intended to help consumers make healthier decisions as well as encouraging businesses to reformulate and offer lower calorie options. Local authorities in England have enforcement responsibility for the Calorie Labelling (Out of Home Sector) (England) Regulations 2021. These regulations were introduced on 1 April 2022 and their effectiveness will be reviewed by April 2026.

Under the Healthy Weight: Healthy Wales delivery plan 2021 to 2022, the Welsh Government will consult on mandatory calorie labelling for food purchased and eaten outside the home in 2022. The Scottish Government’s Out of Home action plan also committed to consult on detailed proposals for mandatory calorie labelling of food and soft drinks sold out of home. This consultation was published on 8 April 2022.

Reducing food waste

In 2019, the FSA, FSS and government departments worked with waste reduction organisations to produce official guidance to help businesses apply the appropriate date marks on their products.

This encourages businesses to consider their food production methods and whether best before dates would be appropriate, particularly if the food will not actually become unsafe for human consumption. Unlike products with a use by date, which concerns food safety, food beyond its best before date does not automatically need to be thrown away. In general, the more businesses are able to apply best before dates to their products, the longer consumers have to make use of them – which, in turn will help reduce food waste.

Improving precautionary allergen information

Work is also underway to improve the way food businesses communicate the risk of allergen cross-contamination of food products. This is where traces of allergens may be found in certain products as a result of the way the food or its ingredients are manufactured or prepared. From December 2021 to March 2022, the FSA consulted on how to develop better precautionary allergen information standards to signpost these risks.

Public confidence in food information

What impact is all of this having on the public’s perspective on food information standards?

Latest figures from the FSA’s Food and You 2 survey found that over eight in ten people (83%) are confident that the information on food labels is accurate. For those who shop for someone with a food allergy or intolerance, the same proportion (83%) felt confident in the allergen information provided on food labels.

People had the highest confidence in being able to identify allergens in food when shopping at a supermarket (71% in store and 69% online), or at independent food shops (67%). Respondents were less confident when buying from markets or stalls (57%).

In Scotland, figures from FSS’s Food in Scotland survey show a similar picture, with 70% of people saying they trust the information on food labels. Among those with food allergies, almost three-quarters (72%) found it very easy or quite easy to find allergen information when buying food in supermarkets.

There are also some broader areas of public concern. The FSA and FSS’s UK Public’s Interests, Needs and Concerns Around Food research shows that around six in ten of us believe that foods labelled as “healthier options” are unhealthy in other ways.

Compliance with food information standards

Both the FSA and FSS undertake regular sampling activity to check whether products available in shops around the country meet a range of safety, authenticity and food information requirements. The most recent sampling activity provides an important snapshot of how well food businesses upheld standards during the pandemic.

Baskets of foods survey

In 2020, early in the COVID-19 pandemic, the FSA launched a survey to check the safety and composition of food on the market in England and Wales. This was followed in 2021 with similar testing in a 'basket of foods’ survey. Its aim was to take a snapshot of compliance to food safety and standards, including the presence of allergens and contaminants, as well as consumer information relating to authenticity and labelling.

The commodities and tests were determined by a cross-government sampling group consisting of the FSA, FSS and Defra. Products were chosen because of prior

authenticity issues (such as basmati rice, herbs and spices), and supplemented with some commonly consumed foods (such as bread and milk). It was not a random sample of all available products. Moreover, the majority of samples were taken from smaller food businesses across the country (including retail outlets and online), which undertake less routine sampling than large food businesses. Figure 30 shows where samples were collected. Sampling and testing were carried out by Public Analyst Official Laboratories, which are responsible for undertaking enforcement testing of food and feed.

Figure 31 shows the types of testing conducted for each product or commodity group, the number of samples tested, and the percentage of unsatisfactory results. Overall, the results of the survey showed that 89% of products tested were compliant with respect to the specific standards we tested (figure 32). The majority of non-compliances found were for labelling and composition.

Figure 30: Location of samples taken as part of the basket of foods survey and the result

The FSA's sampling activity showed high levels of compliance in most categories - with some notable exceptions

Figure 31: The FSA's basket of foods survey: results by food category

The number of samples taken within each food category is shown, with the number of non-compliant samples given in brackets.

| Commodity | Labelling | Authenticity | Allergen | Composition | Containment | Adulteration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basmati rice | - | 18 (3) | - | - | - | - |

| Bread | 26 (2) | - | 26 (6) | - | - | - |

| Cheese | 29 (0) | 29 (0) | - | - | - | - |

| Dairy free from | 29 (1) | - | 29 (1) | - | - | - |

| Gluten free from | 30 (4) | - | 30 (0) | - | - | - |

| Milk | 31 (0) | - | - | 31 (6) | - | - |

| Olive oil | 29 (1) | 29 (0) | - | 29 (1) | - | - |

| Orange juice | 30 (2) | - | - | 30 (0) | - | - |

| Oregano | - | 30 (1) | - | 30 (4) | 30 (0) | 30 (0) |

| Pasta | - | - | - | - | - | 30 (0) |

| Peanut free from | 30 (4) | - | 30 (0) | - | - | - |

| Turmeric | - | 30 (0) | - | - | 30 (2) | 30 (0) |

| Vegan products | 24 (3) | - | 24 (0) | - | - | - |

| Total percentage of non-compliance (by issue) | 7 | 3 | 5 | 9 | 3 | 0 |

Figure 32: Overall percentage of samples deemed satisfactory, with type and proportion of non-compliance by food category

Percentages might not add up to 100% due to rounding.

Notable concerns included the presence of allergens in seven samples that were not declared on the label, with all but one of these in bread. This represents 5% of the samples tested for non-declared allergens and these were reported as incidents by the FSA. Authenticity breaches were reported in one sample of oregano (adulterated with olive leaf) and three of basmati rice (adulterated with non-basmati rice). These samples represented 3% of the total number of samples tested for authenticity.

There were also cases where composition was not consistent with legal requirements. The fat content of 19% of the milks tested was not consistent with the label, with values both above and below those declared and all outside of permitted limits (with deviation ranging from 2 to 17% of the permitted limits).

For many other products (such as some vegan and 'free from' products), unsatisfactory results related to technical aspects of labelling and did not represent a specific public health issue – for example, issues with the readability of the font type used to provide allergen information and precautionary cross-contamination statements for consumers.

Overall, this survey provides reasonable products, especially given that sampling was targeted at high-risk areas. A small number of safety issues were identified (less than 3% of total samples tested), reinforcing the need for a regular sampling programme and enforcement, especially for allergens. However, a considerable number of products tested did not meet required standards in at least one area, especially regarding labelling and provision of consumer information, emphasising the need for further guidance to industry and ongoing monitoring.

While this was not a representative survey, it highlights the need for ongoing surveillance and the FSA is planning further sampling in 2022-23. Meat and meat product sampling will be covered in next years' report.

FSS annual targeted food sampling programme

FSS also undertakes an annual targeted food sampling programme. Sampling priorities selected each year are informed by intelligence and trends gathered from the Scottish Food Sampling Database (SFSD), horizon-scanning activities, issues identified by local authorities and through liaison with others (including the FSA). The programme covers both food safety and food standards issues, the latter including authenticity and allergen testing, as well as labelling analysis.

Data presented in this chapter focuses only on food standards issues and excludes any of the food safety data obtained in this reporting period. Results from targeted sampling undertaken in 2021 show generally high levels of compliance, with 90.2% of samples returning satisfactory results (figure 33). The majority of tested commodities had a low number of unsatisfactory results, which provides a reasonable degree of confidence that sampled products are meeting the required food standards.

However, the highest failure rate found in pre-packed beef mince (25%), where declared fat in the final product was higher than that stated on the label, is concerning. While this does not present a food safety issue, consumers need to have confidence in the accuracy of labelling information, which underlines the need for appropriate investment in ongoing sampling and monitoring, and, where necessary, enforcement action. Any identified non compliances will inform FSS’s future sampling priorities.

Figure 33: Overall percentages of samples assessed as satisfactory or unsatisfactory in FSS's sampling activity (2021)

Looking to the future

To stay relevant and effective, our food information standards must keep pace with the needs of the consumer and the key developments taking place across our food system.

Technology is a particularly important catalyst. With more people purchasing food online, both the FSA and FSS are exploring how they can work with businesses to ensure the consistency and quality of information available to the consumer, whether buying in-store or on a website, is maintained.

At the same time, the increasing number of food businesses trading via social media or other online marketplaces is making it harder to monitor compliance within food information laws in a consistent way.

Other pressures on food information standards are external. Major disruption to supply chains – as seen recently as a result of the war in Ukraine – is likely to increase the risk of misleading labelling, especially if ingredients or products are changed at short notice. The FSA and FSS work closely with the food industry and enforcement officers in these cases to ensure consumers are kept informed.

And finally, any future decisions on food information standards in Great Britain must continue to pay close attention to changes in EU law in light of the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland.

In summary

- this has been a period of consolidation following the UK’s departure from the EU. There has been extensive legislation put in place and detailed work done with the food industry to maintain business continuity and market access, though much of this will not have had any noticeable impact on the consumer to date

- the UK’s food labelling laws have developed in recent years. The introduction of new rules on allergen labelling and mandatory calorie menu information laws are expected to improve the quality of information available to consumers. We will monitor the effectiveness of the changes, taking account of feedback from consumers, businesses and enforcers. A review of changes to the labelling of prepacked foods for direct sale will take place in 2022.

- post-EU Exit systems and structures for overseeing food information standards have also been established, in particular the creation of the new UK Nutrition and Health Claims Committee to assess proposed nutrition and health claims