Consumer Insights Tracker Report July 2023 - March 2024: Detailed Findings

This section of the report presents detailed findings from the Consumer Insights Tracker between July 2023 to March 2024.

Consumer concerns about food

What were consumers most concerned about in relation to food?

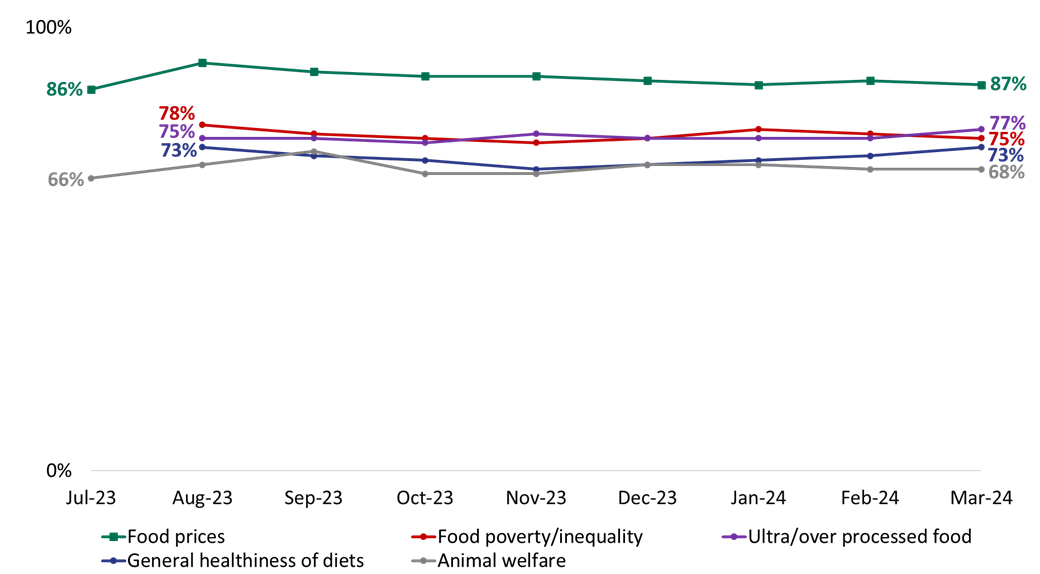

When prompted with a number of different issues related to food in the UK, the issue the highest number of consumers were concerned about was food prices (87% in March 2024), followed by ultra-processed, or the over-processing, of food (77%) and food poverty and inequality (75%). The next most commonly reported concerns were around the healthiness of people’s diets in general (73%) and animal welfare within the food industry (68%) (footnote 1).

Concern about food prices was also the most common concern in the previous year of the Consumer Insights Tracker and has been a top concern in Food and You 2 over recent waves, highlighting its pertinence as an issue over time.

As can be seen in Figure 1, the top concerns have remained relatively stable over time. For each of the top issues, concern in March 2024 is no more than 3 percentage points higher or lower than in July/August 2023 when tracking began. Concern for food prices has seen the largest variation (from a low of 86% in July 2023 to a high of 92% in August 2023) though it is worth noting this is a minimal difference (in terms of the percentage point difference).

Figure 1. General concern for food issues in the UK over time (footnote 2)

Who was most concerned about food prices?

Concern for food prices was high across the board. Whilst there were some differences by demographic group, these tended to be minimal and for all groups reported concerned was above 80%. For example, whilst concern was higher among those with household incomes of <£20k (90%) or between £20k-£35k (93%), this was not much higher than those with a household income of £35k-60k (87%) or more than £60k (82%). This same pattern has been seen since July 2023.

Who was most concerned about food poverty and inequality?

Concern about food poverty and inequality was generally high, though it was particularly high for:

- Women (80% vs. 70% of men)

- Those in the younger or middle age brackets (78% of 16-34 year olds and 79% of 35-54 year olds vs. 69% of those aged 55+)

- Those from ethnic minority backgrounds (84% vs. 74% of White respondents)

- Those with higher educational attainment (84% of those with a degree, masters or PhD vs. 68% of those with no formal qualifications)

There were not differences in levels of concern by measures of income such as social grade, gross household income or IMD.

Who was most concerned about ultra-processed or the over-processing of food?

Whilst concern for ultra-processed food was high across all demographic groups, it was particularly high for:

- Those in the middle and older age brackets (80% of 35-54 year olds and 82% of those aged 55+ vs. 69% of 16-34 year olds)

- Those in higher social grades (81% of AB and 80% of C1 vs. 72% of C2 and 74% of DE)

- Those who know a lot or a little about the FSA (84% vs. 62% of those who haven’t heard of FSA)

There were not big differences by nation, though concern regarding ultra-processed food was marginally higher in Northern Ireland (78%) and England (76%) than in Wales (72%). (footnote 3)

There was also relatively high concern around ingredients and additives in food (68%) and genetically modified (GM) food (55%). The patterns by age, with higher concern among those in the middle and older age brackets, also existed when considering the ingredients and additives in food and GM food.

Household food affordability

In addition to being asked how concerned they were about a range of food-related issues, including food prices, respondents were asked about their level of worry regarding food affordability for themselves/their household in the next month.

How have worries about food affordability changed over time?

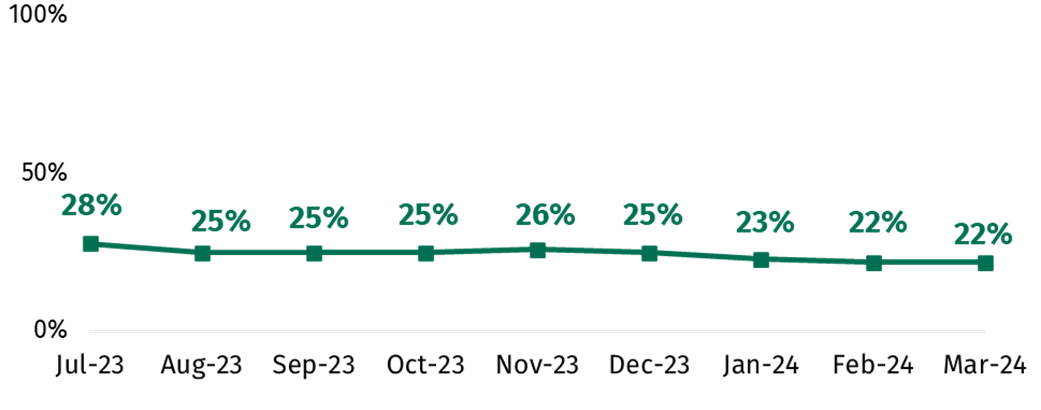

The proportion saying that they were worried about their household’s ability to afford food in the next month has declined gradually across the tracking period, falling from a peak of 28% in July 2023 to a low of 22% in February and March 2024 (Figure 2). This suggests that fewer people were worried about food affordability specifically related to their own household compared to general concerns about food prices in the UK, although this is still something around one in four people are worried about.

Figure 2. Worry about food affordability over time (footnote 4)

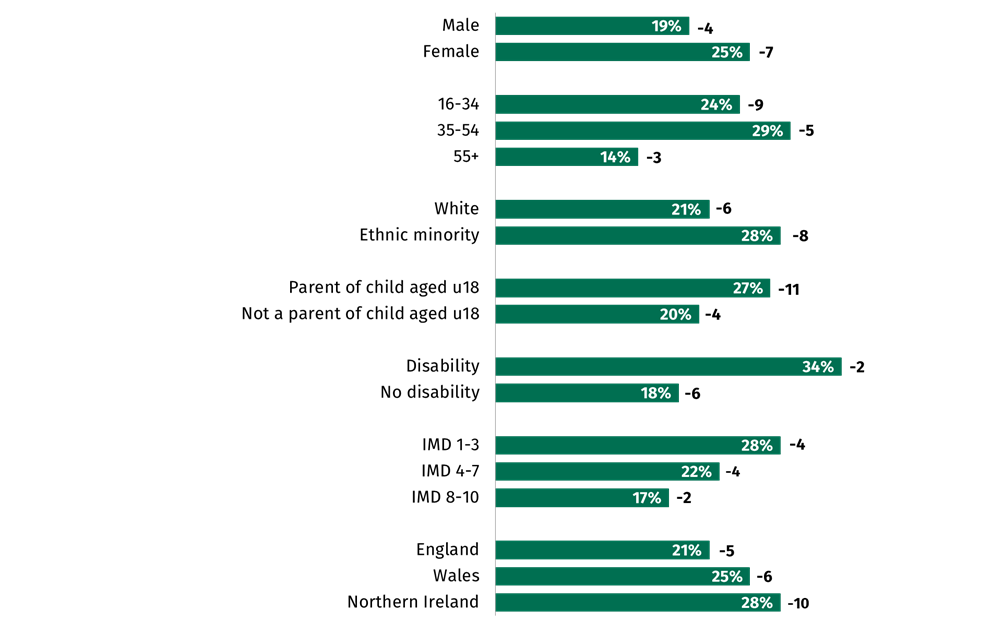

Who was most impacted by food affordability worries?

Groups most likely to report being worried about food affordability included those limited by a disability or long-term health condition, those aged under 55, those in the most deprived IMD deciles, those from ethnic minority backgrounds and those living in Northern Ireland. As shown in Figure 3 below, these groups were more likely to report being worried about their household’s ability to afford food in the next month. While the results shown in Figure 3 are for March 2024, these gaps were consistent across months. Differences in comparison to July 2023 (in percentage points) are shown as numbers next to the bars.

Figure 3. Concern about food affordability among key demographic groups (footnote 5)

Note: Difference vs. July 2023 noted beside each group.

While levels of worry about food affordability declined across the tracking period among almost all demographic groups, these declines were larger among the groups reporting higher levels of initial worry about food affordability. This may indicate that these groups are somewhat more sensitive to changing economic conditions over time, with their levels of worry fluctuating more widely in line with changes in food prices and other cost-of-living challenges. The only exception here was among those limited by a long-term health condition or disability, for whom worries about food affordability remained higher and broadly unchanged from July 2023 - March 2024.

How have food shopping behaviours changed in response to the rising cost of living?

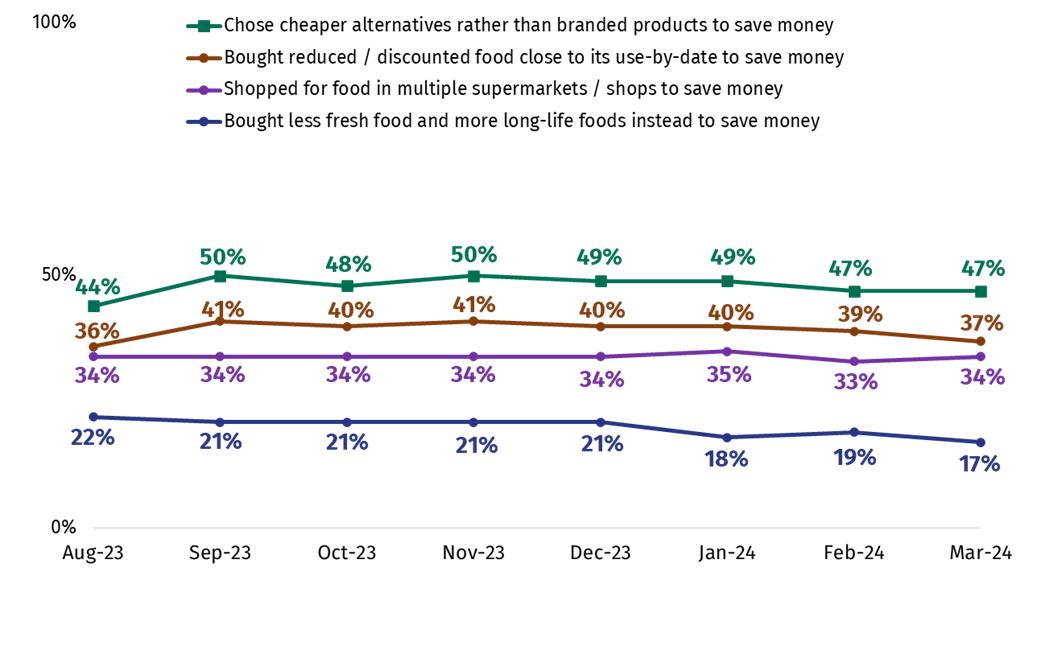

The most common ways of saving money when food shopping were choosing cheaper alternatives rather than branded products (47%), buying reduced/discounted food close to its use-by date (37%) and shopping around in multiple shops (34%), while 17% mentioned buying less fresh foods and more long-life foods instead. As can be seen in Figure 4, apart from an increase in the proportions reporting doing each of these things between August and September 2023, their incidence has remained stable across the tracking period.

Figure 4. Most common shopping behaviours over time (footnote 6)

It was less common for people to report being unable to afford their essential food shopping in general; four percent reported this in March. A slightly higher figure said they could not afford to buy food that meets their animal welfare or environmental values (6% in March 2024), though this has declined slightly from a high of 8% in September 2023.

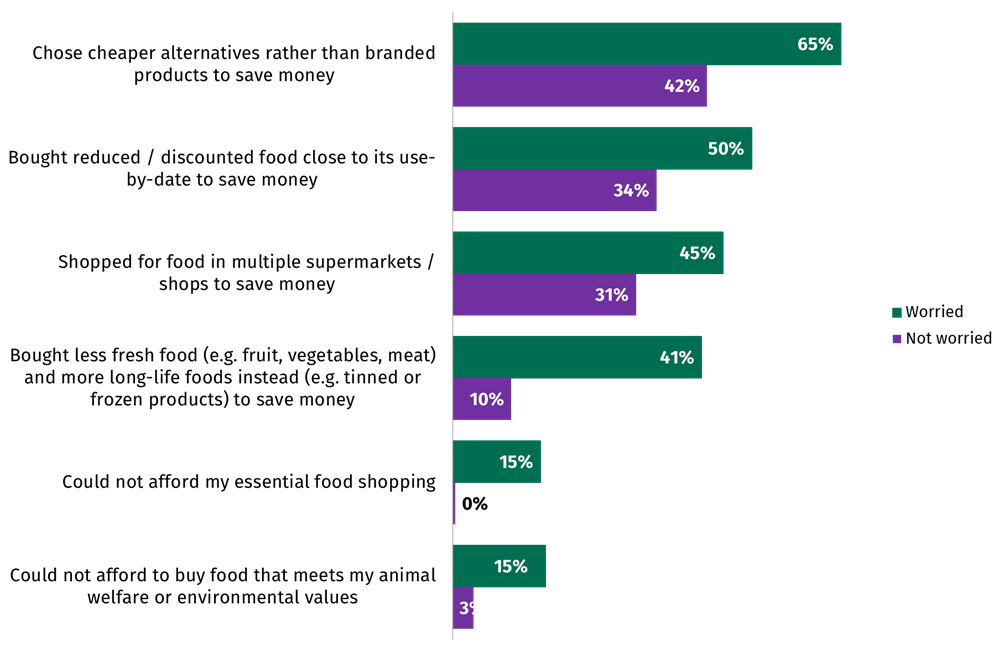

Those who were worried about their household’s ability to afford food in the next month were more likely to report making changes to their shopping behaviours to save money (Figure 5). They were also more likely to report having been unable to afford their essential shopping in the last month. These trends were consistent over time.

Figure 5. Shopping behaviours by level of worry about food affordability (footnote 7)

How have cooking and eating behaviours changed in response to the rising cost of living?

Across the survey, the most common way of reducing costs when cooking or eating was using cheaper cooking methods (e.g. using a hob, a microwave, air fryer or slow cooker) instead of an oven to heat or cook food (55%), followed by cooking/preparing food from scratch, rather than buying it (37%); both of these figures have stayed broadly stable across survey waves. Bulking out meals with cheaper ingredients was mentioned by 17%, while eating food past its use-by date, cutting the size of meals/skipping meals and being unable to afford to eat a healthy balanced diet were all reported by 9% in March 2024.

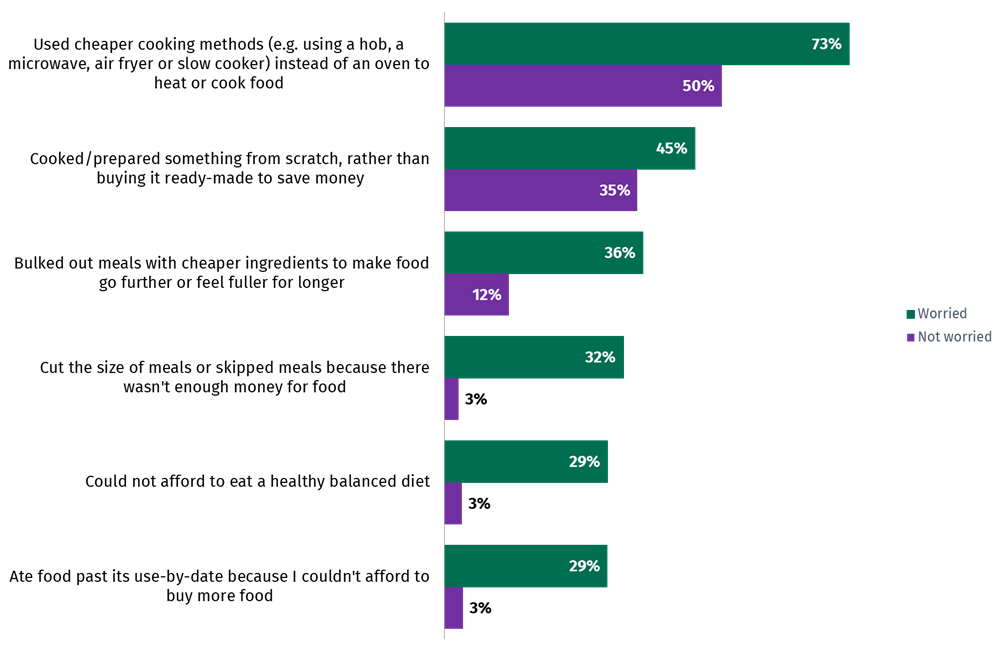

As was the case with shopping behaviours, those who were worried about food affordability were more likely to report that the statements above applied to them (Figure 6). Around three in ten (29%) of those who were worried about food affordability reported eating food past the use-by date because they couldn’t afford to buy more food in the last month, whereas only 3% of those who weren’t worried about food affordability reported doing this. These trends were again consistent over time and hold when analysing demographic differences, with the groups most worried about food affordability consistently more likely to report that these behaviours apply to them.

Figure 6. Cooking and eating behaviours by level of worry about food affordability (footnote 8)

Has trying to save money led people to practice risky food behaviours?

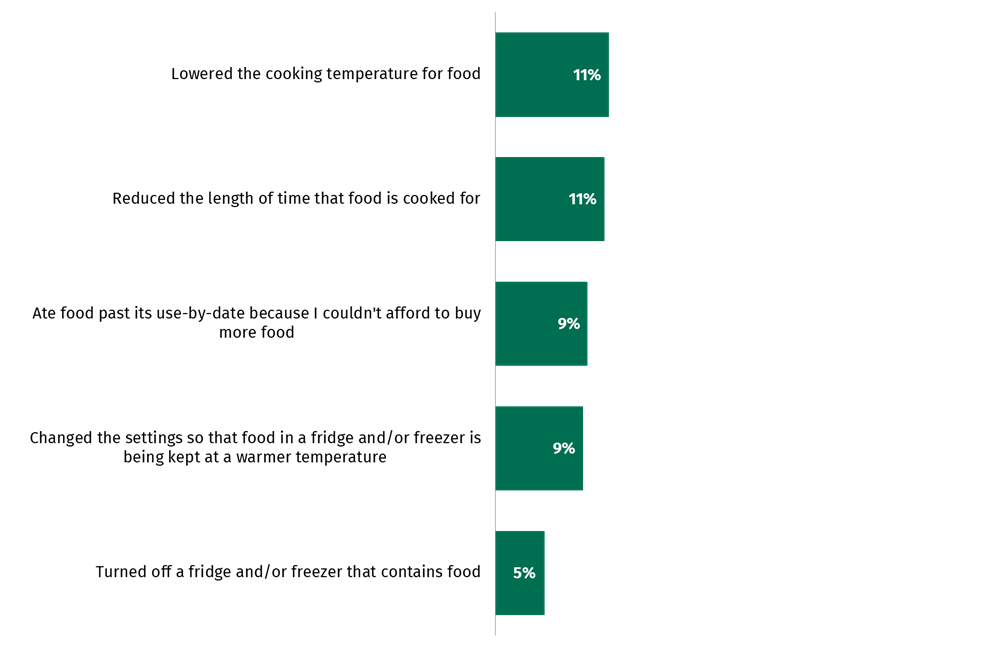

Respondents were asked whether they had taken a number of food-related actions in the last month in order to reduce their energy bills and save money. Specifically, the actions listed aimed to measure the prevalence of certain ‘risky’ food-related behaviours. These included reducing the length of time food is cooked for; lowering the cooking temperature for food; turning off a fridge/freezer containing food; changing fridge/freezer settings to a warmer temperature; or eating food past its use-by date.

As can be seen in Figure 7, the proportion reporting having done each of these in the last month was relatively low. In March 2024, 11% reported lowering the cooking temperature for food and the same proportion said this about reducing the length of time food is cooked for. Less than one in ten mentioned eating food past its use-by date (9%), keeping their fridge/freezer at a warmer temperature (9%) or turning off a fridge/freezer that contained food (5%) in order to save money. Again, these figures remained broadly steady across the 9-month period.

Figure 7. Proportion reporting each risky food behaviour (footnote 9)

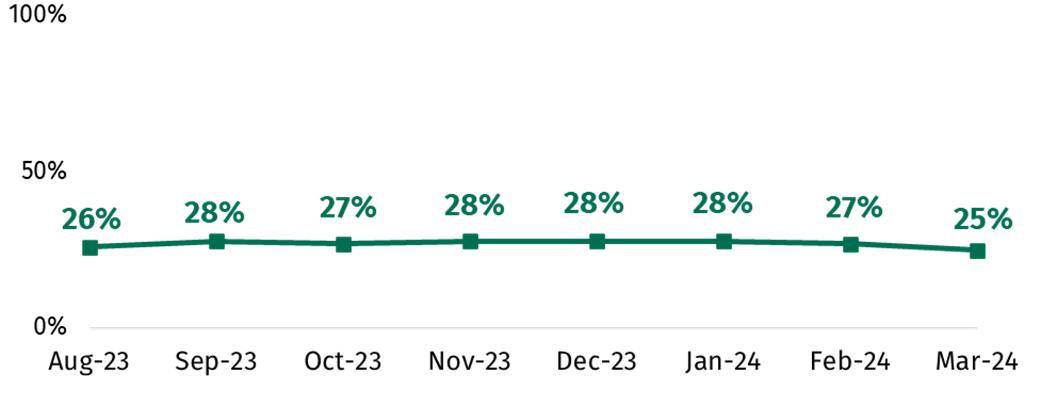

However, one in four (25%) of those in England, Wales and Northern Ireland reported they have done at least one ‘risky’ food behaviour in the last month as of March 2024 (Figure 8), a figure which has remained broadly stable across survey waves. Those worried about food affordability (58%) were much more likely to report doing these than those not worried (15%), indicating that these methods are used quite frequently by some in order to save money. Those from an ethnic minority background (39%), those limited by a health condition or disability (35%), those in the most deprived IMD deciles (34%), and those aged under 35 (30%) were also more likely to report these kinds of behaviours. These trends were consistent across the tracking period.

Figure 8. Proportion reporting at least one risky food behaviour in the last month (footnote 10)

These included reducing the length of time food is cooked for; lowering the cooking temperature for food; turning off a fridge/freezer containing food; changing fridge/freezer settings to a warmer temperature; or eating food past its use-by date.

How has food bank usage changed over the last 8 months?

The proportion who reported that they or someone in their household had received a free parcel of food from a food bank or emergency food provider has remained broadly comparable, at between 2-4% across the 9-month tracking period (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Proportion reporting using a food bank in the last month (footnote 11)

The relatively low incidence of food bank usage makes it more difficult to detect statistically significant differences across demographic groups for individual months. However, combining the data for the first three months of 2024 revealed the following trends in usage:

- One in twenty (5%) of those in the most deprived IMD deciles reported using a food bank in the last month, compared to 1% of those in the least deprived deciles

- The same proportion (5%) of those limited by a health condition or disability reported using a food bank in the last month, compared to 2% of those not limited

- 5% of those with children under 18 living in their household had used a food bank, compared to 2% without children under 18 living in their household

- Food bank usage rises with household size; 5% of those in households with 4 or more people have used one in the last month, compared to 2% with 1-3 people

- Usage was three times higher among those from an ethnic minority background than White respondents (6% vs. 2%)

- Usage was higher in Wales (5%) than in England or Northern Ireland (both 3%). It was also higher in London (6%).

Food availability

How have worries about food availability changed over the last 9 months?

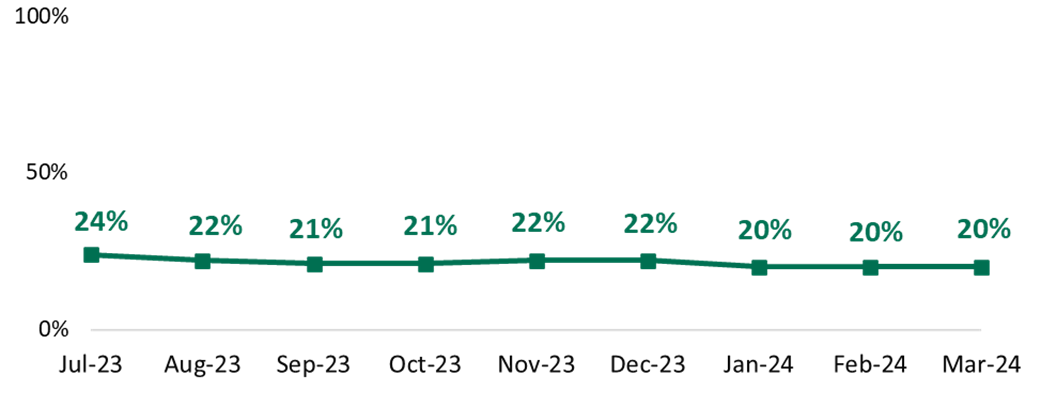

The proportion who said that they were worried about there not being enough food available for them (or their household) has slowly declined since July 2023 (24%), though has been generally stable across the tracking period. This can be seen in Figure 10. This means the majority were either not very or not at all worried about this in March 2024 (78%).

Figure 10. Worry over food availability over time (footnote 12)

Who was most worried about food availability?

Groups most worried about food availability include:

- Those in the younger and middle age brackets (23% of 16-34 year olds and 25% of 35-54 year olds vs. 12% of those aged 55+)

- Those from ethnic minority backgrounds (30% vs. 18% of those from White backgrounds)

- Those in the lowest income bracket (33% of those with a household income of <£20k vs. 12% of those with a household income of £60k or more)

- Those limited a lot by a health condition or disability (42% vs. 16% of those who are not limited)

Confidence in the food supply chain

How has confidence in the food supply chain changed over time?

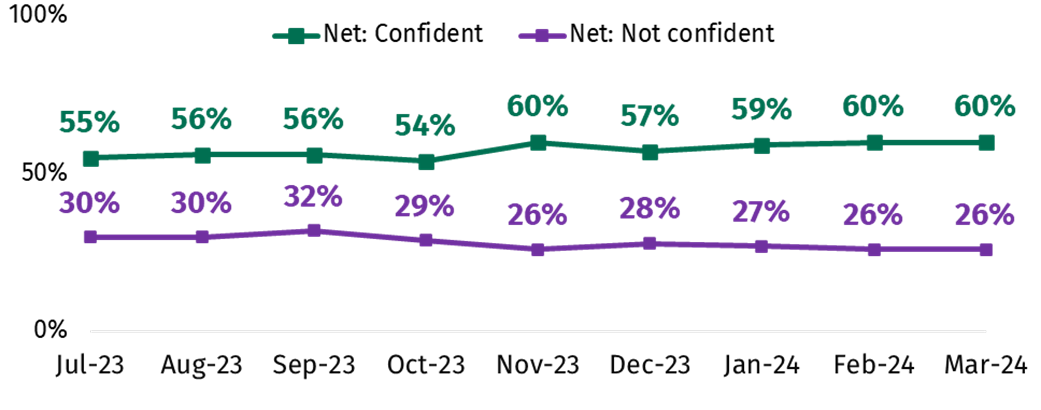

Overall confidence in the food supply chain has increased gradually from 55% in July 2023 to 60% in March 2024. The proportion who said they are not confident declined by four percentage points during the same period, from 30% to 26%. This can be seen in Figure 11.

This confidence was particularly driven by perceptions of food safety, availability and quality. Three in four (73%) said that they were confident that those involved in the food supply chain ensure that food is safe to eat, while 59% said this about there being enough food available to eat, and 56% that they ensure food is of high quality. Levels of confidence relating to availability and safety rose marginally by 3 and 4 percentage points, respectively, from July 2023 to March 2024, while for quality this figure remained steady.

Confidence was lower when it comes to food affordability, with only 39% saying that those involved in the food supply chain ensure that there are affordable food options for everyone, compared to 52% who were not confident. Lower levels of confidence in this aspect of the supply chain are likely a reflection of people’s general concerns about food prices in the UK.

Figure 11. Confidence in the food supply chain over time (footnote 13)

Which groups expressed the lowest levels of confidence in the food supply chain?

The groups most likely to say they are not confident in the food supply chain included:

- Those limited by a health condition or disability (31%), compared to 25% of those who are not limited

- Those in urban areas (27%), compared to 22% in rural areas

- Those in Wales (32%), compared to 29% in England and 26% in Northern Ireland

Trust and confidence in the FSA

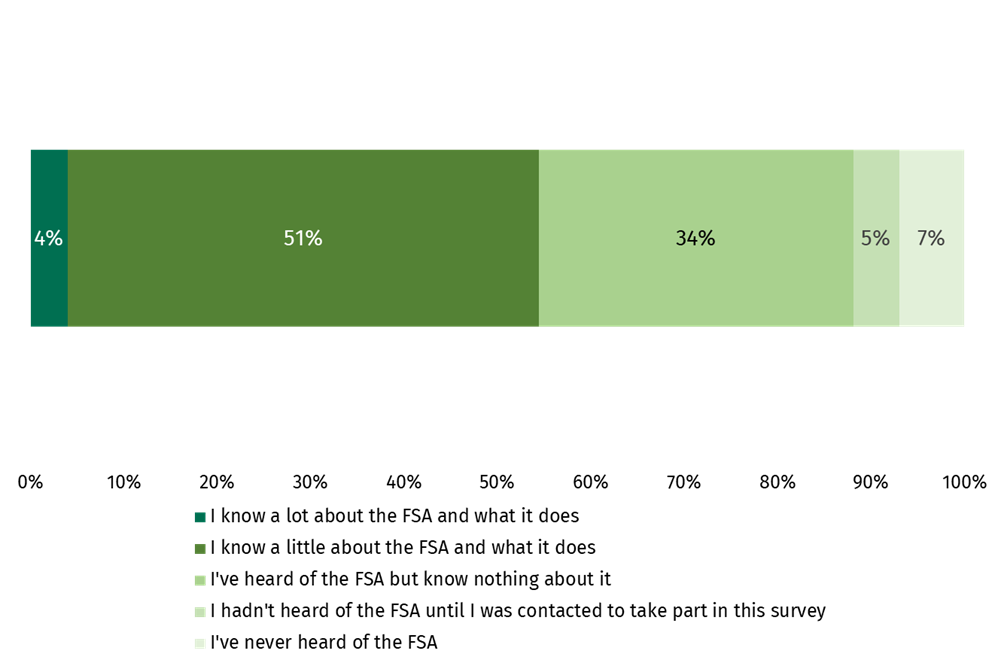

How many people reported knowing about the FSA?

Over half (55%) said they have at least some knowledge of the FSA, although the majority of this figure was made up of people who said they know ‘a little’ (51%), compared to just 4% who said they know ‘a lot’ (Figure 12). An additional 34% reported that they had heard of the FSA but know nothing about it, meaning that awareness of the organisation was 89% overall in March. These figures were unchanged across the tracking period.

Figure 12. Knowledge of the FSA (footnote 14)

Self-reported knowledge of the FSA was higher among certain groups, including those aged 55+ (63% vs. 59% of those aged 35-54 and 40% of those aged under 35), white respondents (56% vs. 45% from an ethnic minority background), those in social grade AB (61% vs. 50% in DE), parents of children under 18 (57% vs. 51% of those without children) and those limited by a disability or long-term health condition (57% vs. 51% of those not limited).

For the remainder of this section on trust, analysis is filtered to only include those with some knowledge of the organisation (footnote 15), as it is adjudged that this is a more reliable measure for tracking trust over time.

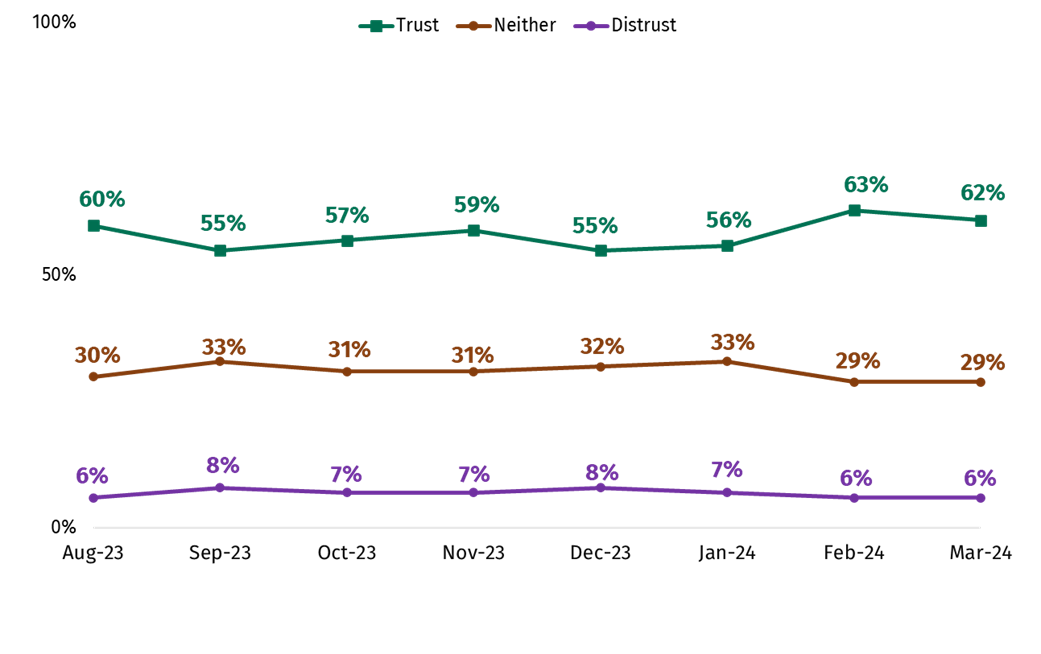

How has trust in the FSA changed over time?

Among those with some knowledge of the FSA and what it does, trust in the organisation has fluctuated across the tracking period. As Figure 13 below shows, the proportion that trust the FSA to do its job has increased from its most recent low of 55% in December 2023 to 62% as of March 2024. The proportion who reported that they do not trust the FSA was between 6% and 8% across this period; this means that any changes in overall trust were partially a result of more people saying they ‘neither trust nor distrust’ the FSA, which was at 29% in March 2024.

Figure 13. Trust in the FSA over time (among those who have some knowledge about the FSA) (footnote 16)

How confident were people in the FSA’s ability to carry out its functions?

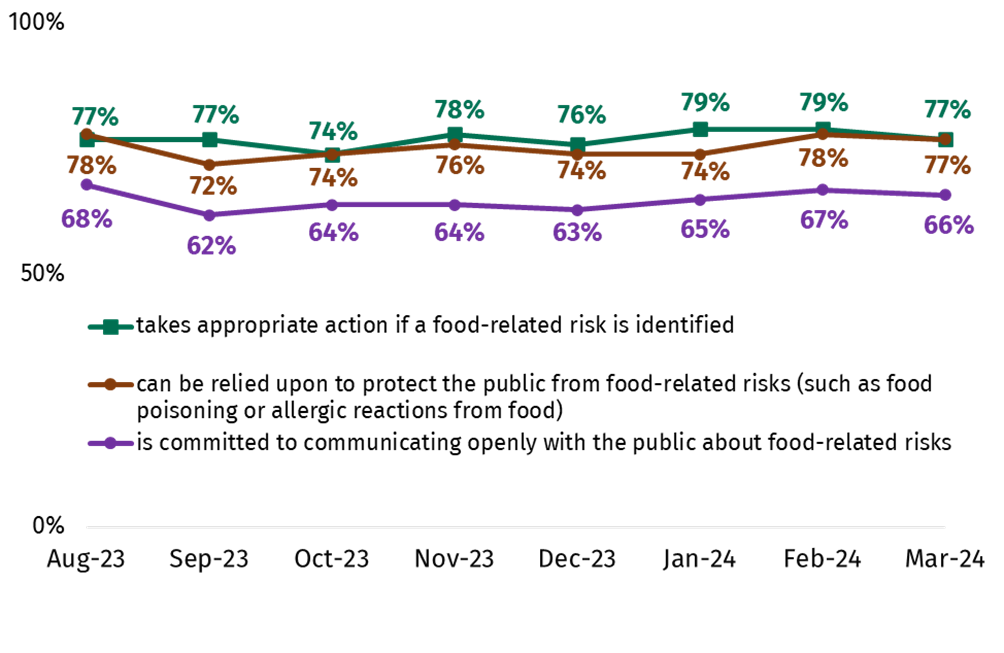

Overall, there was high confidence in the FSA’s ability to carry out its functions. In terms of the functions the FSA carries out, 77% were confident that it can be relied upon to protect the public from food-related risks, while the same proportion were confident that it takes appropriate action regarding food-related risks (77%). Both of these figures have remained stable across the tracking period since August 2023 (Figure 14).

Confidence that the FSA is committed to communicating openly with the public about food-related risks was somewhat lower, though remains a majority at 66%. This figure has again remained stable since last August.

Figure 14. Confidence in various FSA functions over time (among those who have some knowledge of the FSA) (footnote 17)

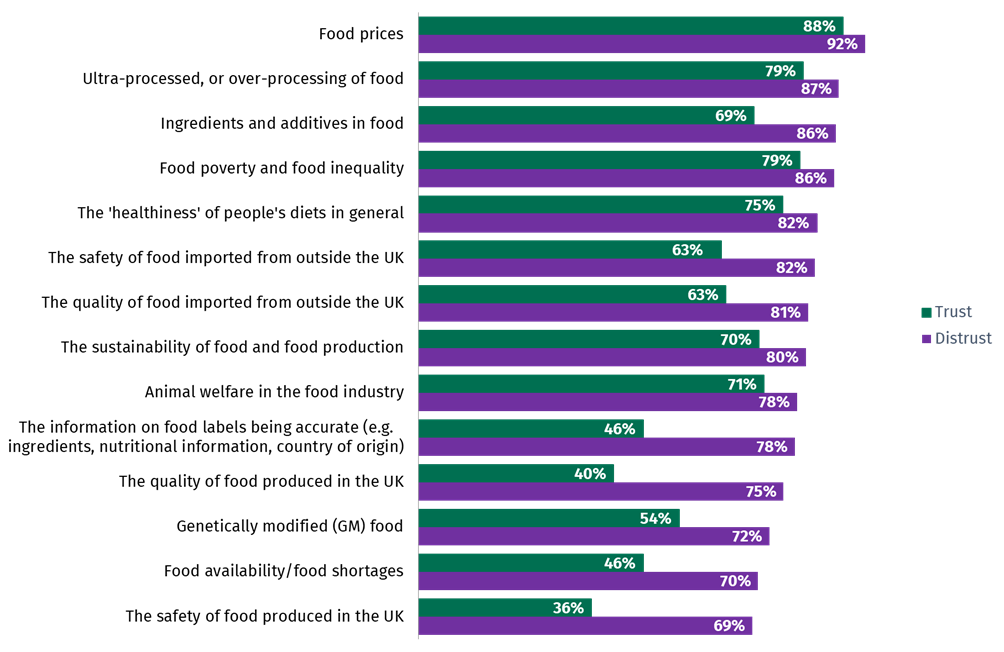

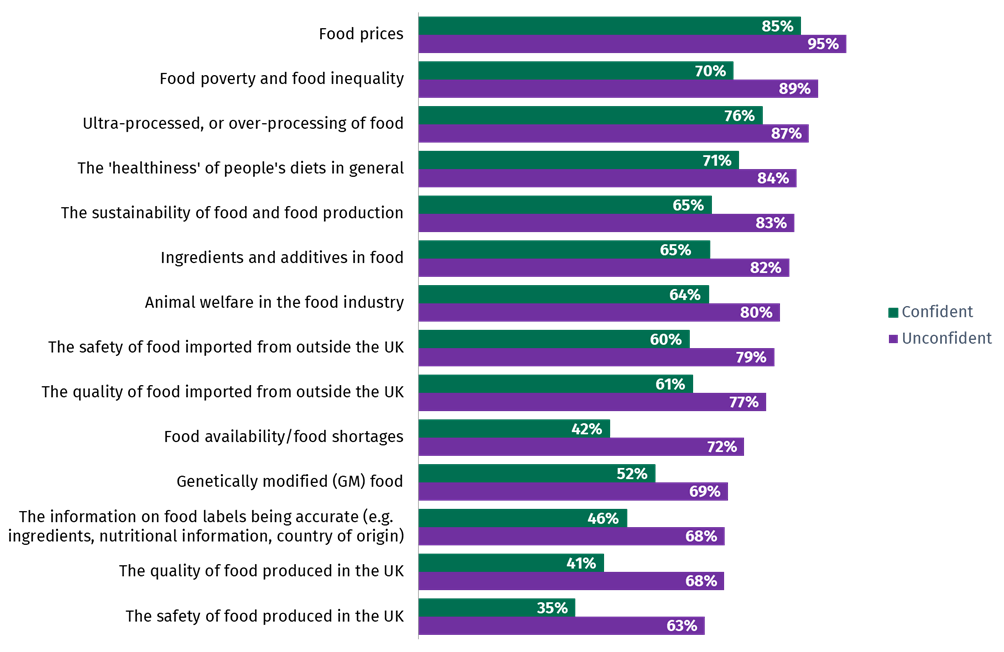

Do those who trust the FSA have more or less concerns about food?

Those who trust the FSA were generally less likely to be concerned about all food-related issues asked about, compared to those who did not trust the FSA. The issues where there were the largest differences in the level of concern between those who trusted and distrusted the FSA were the safety of food produced in the UK (69% vs. 36%), as well as its quality (75% vs. 40%), while similar differences were also seen when it comes to food imported to the UK (footnote 18). As Figure 15 below shows, those who distrust the FSA were also more likely to be concerned about ultra-processed food, ingredients and additives in food and GM food, as well as the accuracy of food labelling. (footnote 19)

Figure 15. Concerns about food in the UK by trust in the FSA (footnote 20)

A similar pattern was observed when comparing concerns by level of confidence in the food supply chain, as can be seen in Figure 16 below.

Figure 16. Concerns about food in the UK by confidence in the food supply chain (footnote 21)

Which groups expressed lower levels of trust in the FSA?

The proportions who said they distrust the FSA were low with few notable differences between demographic groups. However, there were some groups less likely to say they trust the organisation, including:

- Women (56%), compared to 67% of men

- Those aged 35-54 (57%) and those aged 55+ (59%), compared to 74% of those aged under 35

- Those limited by a health condition or disability (53%), compared to 65% of those who are not limited

-

The survey prompted respondents with a list of 14 different food related concerns (e.g. including food availability/shortages and the safety and quality of food and food labelling) and asked them how concerned, if at all, they were about each of them.

-

[Q12] Thinking about food in the UK in general. At the moment, how concerned, if at all, do you feel about each of the following topics? Base: All in March 2024 (n=2,015), February (n=2,066), January (n=2,038), December (n=2,026), November (n=2,064), October (n=2,062), September (n=2,057), August (n=2,044) and July 2023 (n=2,085).

-

Due to small base sizes in Northern Ireland and Wales each wave, data at the nation level has been rolled up for the past 3 months (January – March 2024).

-

[Q3m] To what extent, if at all, are you worried you/your household will not be able to afford food in the next month? Base: All in March 2024 (n=2,015), February (n=2,066), January (n=2,038), December (n=2,026), November (n=2,064), October (n=2,062), September (n=2,057), August (n=2,044) and July 2023 (n=2,085).

-

[Q3m] To what extent, if at all, are you worried you/your household will not be able to afford food in the next month? Base: All male (n=993), female (n=1,022), 16-34 (532), 35-54 (636), 55+ (847), White (1,795), Ethnic minority (185), child aged under 18 in household (570), no child aged under 18 in household (1,394), disability/limiting health condition (559), no disability/limiting health condition (1,431), IMD 1-3 (521), IMD 4-7 (808), IMD 8-10 (686), England (1,811), Wales (100), Northern Ireland (104) in March 2024.

-

[Q6] In the last month, did any of the following apply to you, or someone else in your household? Base: All in March 2024 (n=2,015), February (n=2,066), January (n=2,038), December (n=2,026), November (n=2,064), October (n=2,062), September (n=2,057), August (n=2,044) and July 2023 (n=2,085).

-

[Q6] In the last month, did any of the following apply to you, or someone else in your household? Base: All worried (n=434) and not worried (n=1,549) about food affordability in March 2024.

-

[Q6] In the last month, did any of the following apply to you, or someone else in your household? / [Q8m] In the last month, which, if any, of the following have you done to reduce your energy bills and save money? (Used cheaper cooking methods (e.g. using a hob, a microwave, air fryer or slow cooker) instead of an oven to heat or cook food). Base: All worried (n=434) and not worried (n=1,549) about food affordability in March 2024.

-

[Q8m] In the last month, which, if any, of the following have you done to reduce your energy bills and save money? / [Q6] In the last month, did any of the following apply to you, or someone else in your household? (Ate food past its use-by date because I couldn’t afford to buy more food) Base: All in March 2024 (n=2,015).

-

[Q8m] In the last month, which, if any, of the following have you done to reduce your energy bills and save money? / [Q6] In the last month, did any of the following apply to you, or someone else in your household? (Ate food past its use-by date because I couldn’t afford to buy more food). Base: All in March 2024 (n=2,015), February (n=2,066), January (n=2,038), December (n=2,026), November (n=2,064), October (n=2,062), September (n=2,057) and August 2023 (n=2,044).

-

[Q3] In the last month, have you or anyone else in your household received a free parcel of food from a food bank or other emergency food provider? Base: All in March 2024 (n=2,015), February (n=2,066), January (n=2,038), December (n=2,026), November (n=2,064), October (n=2,062), September (n=2,057) and August 2023 (n=2,044).

-

[Q2m] To what extent, if at all, are you worried about there not being enough food available for you/your household to buy in the next month? Base: All in March 2024 (n=2,015), February (n=2,066), January (n=2,038), December (n=2,026), November (n=2,064), October (n=2,062), September (n=2,057), August (n=2,044) and July 2023 (n=2,085).

-

[Q13] How confident are you in the food supply chain? That is all the processes involved in bringing food to your table. Base: All in March 2024 (n=2,015), February (n=2,066), January (n=2,038), December (n=2,026), November (n=2,064), October (n=2,062), September (n=2,057), August (n=2,044) and July 2023 (n=2,085).

-

[Q14a] How much, if anything, do you know about the Food Standards Agency? Base: All in March 2024 (n=2,015).

-

Those who said they know ‘a lot’ or ‘a little’ about the FSA and what it does

-

[Q16] The Food Standards Agency is the Government Agency responsible for food safety in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. How much do you trust or distrust the Food Standards Agency to do its job? That is to make sure that food is safe and what it says it is. Base: All with some knowledge about the Food Standards Agency in March 2024 (n=1,137), February (n=1,127), January (n=1,168), December (n=1,134), November (n=1,183), October (n=1,175), September (n=1,161) and August 2023 (n=1,126).

-

[Q15] The Food Standards Agency is the Government Agency responsible for food safety in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. How confident are you that the Food Standards Agency... Base: All with some knowledge about the Food Standards Agency in March 2024 (n=1,137), February (n=1,127), January (n=1,168), December (n=1,134), November (n=1,183), October (n=1,175), September (n=1,161) and August 2023 (n=1,126).

-

These figures are from January to March 2024

-

Due to small base sizes for those who distrust the FSA within individual months, figures here are based on three months of data from January-March 2024.

-

[Q12] Thinking about food in the UK in general. At the moment, how concerned, if at all, do you feel about each of the following topics? Base: All with some knowledge about the Food Standards Agency who trust (n=2,047) and distrust (n=247) it from January-March 2024.

-

[Q12] Thinking about food in the UK in general. At the moment, how concerned, if at all, do you feel about each of the following topics? Base: All confident (n=1,225) and not confident (n=529) in the food supply chain in March 2024.