Chapter 12 Incident Management

This chapter details incident management

Sections

1. Introduction

In this section

1.1 Overview

This chapter sets out the procedures to be followed when escalating an incident from Field Operations to the Incidents Team.

It provides a definition of those incidents that should be escalated to the Incidents Team. It explains the difference between an incident and an issue or complaint and sets out the criteria for determining when and how you should escalate an incident to the Incidents Team for response.

There are currently multiple routes through which a complaint, issue or incident can be raised within Field Operations. Not all of these complaints, issues or incidents will require escalating to the Incidents Team; many will be handled as they are now, at the local level by Field Operations staff.

The aim of this chapter is to ensure that incidents identified as meeting the definition as described at sub-section 1.3 on Definition are escalated as early as possible to the Incidents Team so that effective and joined up response arrangements can be delivered.

1.2 Incidents Team function

The Incidents Team is responsible for 24/7/365 receipt, management and co-ordination of all food and feed safety incidents received by the FSA. The Incidents Team assures that any food / feed that is not compliant with food safety or other legislative requirements is removed from the market. The Incidents Team acts as the central hub for food and feed incidents work. It maintains the official audit trail for the investigation, co-ordinating the logging, collation and distribution of information required during the investigation. Updated [The Incidents Team arranges the issue of food alerts to local authorities, other government departments, trade organisations and other interested parties including the EC’s Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF) notifications and mirrors FBO recalls to consumers to widen the message.]

1.3 Definition

The following definition of an incident has been taken from the FSA Incident Management Plan (IMP). The IMP defines the FSA’s response to an incident where the FSA takes responsibility, either by statutory requirement or in its role of Lead Government Department or as supporting Department, following an actual or potential threat to the safety, quality or integrity of food and / or animal feed.

The FSA defines an incident as:

“any event where, based on the information available, there are concerns about actual or suspected threats to the safety, quality or integrity of food and / or feed that could require intervention to protect consumers’ interests”.

See section 2.2.1 for escalation triggers.

1.3.1 Food hazards

Updated [A ‘food hazard’ is defined as anything present in food with the potential to harm the consumer, either by causing illness or injury; these can be a biological, chemical, and/or physical agent, or the condition of any food with the potential to cause an adverse effect on the health or safety of consumers (including outbreaks of foodborne disease and/or infectious intestinal disease). In determining whether a food hazard should be notified to the Incidents Team, Field Operations staff should consider the following criteria:

- localised food hazard – one in which food is not distributed by the FBO outside its local authority area and is not deemed to be a serious localised food hazard; should be dealt with locally by the Field Operations staff, in conjunction with other relevant agencies, if required. For example, an isolated consumer complaint of foreign body within the product.

- serious localised food hazard – one in which food is not distributed beyond the boundaries of the FBO’s local authority but which involves or may involve:

- undeclared allergens, a serious anaphylaxis reaction requiring medical intervention as a result of allergens in food, hospitalisation, or death as a result of allergens in food

- shiga toxin producing Esterichia coli, (STEC), or E. Coli O157 or other Verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli (VTEC)

- Clostridium botulinum

- Pathogenic Salmonella serogroups, e.g. typhimurium, Salmonella paratyphi, Salmonella enteritidis, infantis, mikawashima

- Listeria monocytogenes

- Pathogenic organisms in water systems

- Norovirus potentially present in food

- Hepatitis

- Food borne illness, (poisoning or allergic reactions) of vulnerable consumers whilst in the care of the NHS

or which the competent authority considers significant because of, for example, the vulnerability of the population likely to be affected, the numbers involved or any deaths associated with the incident. These should be notified by the Field Operations staff to the Incidents Team and other relevant agencies at the earliest opportunity and by the quickest available means and confirmed in writing using the Food / Feed Incident Report Form (Annex 1).

- non-localised food hazard – one in which food is distributed beyond the boundaries of the local authority area; should be notified by Field Operations staff to the Incidents Team and other relevant agencies at the earliest opportunity and by the quickest available means and confirmed in writing using the Food / Feed Incident Report Form (Annex 1).]

Field Operations staff should seek the advice of the FVC or Incidents Team if in doubt as to whether a food incident amounts to a food hazard.

1.3.2 Food fraud and food crime

Food crime is an umbrella term used to define the remit of the FSA National Food Crime Unit (NFCU). It is not a legal term. In this context food crime means serious dishonesty which has a detrimental impact on the safety or the authenticity of food, drink or animal feed. Food crime can be thought of as serious food fraud. Suspicions or information about food fraud or food crime should be reported to the NFCU by email or by contacting the NFCU directly.

1.3.3 Non-hazardous incidents

Non-hazardous incidents are those which may impact on the food supply chain and may include issues of quality, provenance, authenticity, composition and labelling. Significant food incidents that are not food hazards should be reported to the Incidents Team immediately. In determining significance, consideration should be given to the following factors:

- Breaches of Food Law

- Possible requirement for a co-ordinated response

- The disadvantage to consumers

- Disproportionate impact on a sector of the population

- Distribution beyond the UK

- Reputational damage to England (or the UK)

- Public concern

- Likelihood of media interest.

1.4 Lines of communication

All communication from Field Operations staff to the Incidents Team should be made through the FVC. (via normal lines of communication as summarised in the table below.)

| Advice required by | Technical advice given by |

|---|---|

| MHI | OV |

| UAI | UAI Lead / FVC |

| UAI Lead | FVC |

| cOV (contract OV) | AVM / FVC |

| eOV (employed OV) | FVC |

| FVC | FVL / Incidents Team |

| ITL | FVC |

| AM | FVC |

| OM | FVC / FVL |

Updated [In the absence of the FVC, any issues that fall within the definition of an incident (see sub-section 1.3 on Definition) or escalation triggers (see sub-section 2.2 on Escalation triggers and process) should be reported directly to the Incidents Team using the Food / Feed Incident Report Form (Annex 1).]

2. Procedures

In this section

2.1 Complaints, issues and incidents handling

2.1.1 How complaints, issues and incidents are received

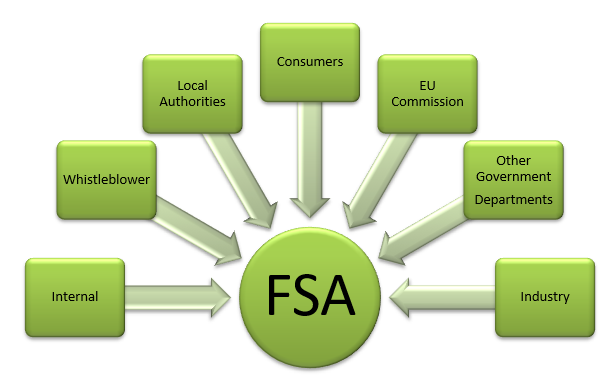

Complaints, issues and incidents regarding food safety issues are received daily by the Incidents Team through a number of routes (see diagram below).

With regard to establishments approved by the FSA (under the remit of Field Operations) the majority of complaints, issues and incidents are received via Corporate Support Unit (CSU).

Whilst most of these complaints, issues and incidents can be dealt with at a local level within the routine day-to-day work of Field Operations staff, it is important to consider at an early stage whether these might highlight a wider issue that should be escalated to the Incidents Team.

Updated [The Food Law Code of Practice requires Field Operations as the Competent Authority to carry out an assessment of the food hazard and notify the FSA Incidents Team if it is assessed as serious and/or non-localised i.e. widespread.]

Early notification to the Incidents Team is crucial in responding to incidents.

For example:

’CSU received a complaint from a member of the public who had found small pieces of metal in packets of ham they had purchased from a specialist deli in their local area. The complainant purchased the ham on three separate occasions over a month and on each occasion found a tiny piece of metal was embedded within the product. Initial investigations by the Deli found that the metal contamination had not occurred on their premises.’

This example has wider implications and risk for consumers. If the product had not been contaminated at the Deli, contamination could have been caused by the way in which the ham has been produced or supplied. There is a real risk this ham has been supplied to other businesses. Therefore, the example should be escalated to the Incidents Team for further investigation.

2.1.2 Updated [Malicious Tampering or Deliberate Contamination

Malicious Tampering and Deliberate Contamination are criminal offences and occur where there is deliberate intention to contaminate and/or threaten to contaminate food or drink.

If there is suspicion of malicious tampering or deliberate contamination, the Head of Incidents should be notified immediately, and the referral confirmed in writing instead of using the incident notification form. The email should be clearly marked as ‘Official Sensitive’.

The officer that identifies or suspects this type of incident must not disclose or discuss the matter with anybody until they have discussed with the Head of Incidents, as there may be a crime in action, or covert response needed, or already underway. The Head of Incidents should advise on handling of the incident as necessary, in communication with the relevant lead authority.]

2.1.3 Responding to a food safety complaint that includes dissatisfaction about the FSA

Where a complaint also includes an expression of dissatisfaction about the FSA, the FSA’s own complaints procedure will also apply. In almost all cases, complaints against the FSA are dealt with at the local level in the first instance and advice on how to proceed can be obtained from CSU transactions. It is standard procedure that responses to complaints against the FSA include details of how the complainant can escalate their case should they be dissatisfied with the response they receive. On escalation, the FSA Complaints Co-ordinator manages the case.

2.1.4 Whistle-blowers

Where a ‘worker’ (a legal definition) contacts the FSA about matters which affect the health of any member of the public in relation to consumption of food and matters which concern the protection of consumers in England, Wales, or Northern Ireland they may be regarded as a whistle-blower and the FSA will then be acting as the ‘Prescribed Person’ within the law.

Whistle-blowing is the term used when a worker passes on information concerning wrongdoing. The wrongdoing may (although not necessarily) be something they have witnessed at work.

To be protected by whistle-blowing law, the disclosure must be a ‘qualifying disclosure’. This is any disclosure of information which, in the reasonable belief of the worker making the disclosure, is made in the public interest and tends to show that one or more of the following has occurred, is occurring or is likely to occur:

- a criminal offence

- a breach of a legal obligation

- a miscarriage of justice or

- the deliberate covering up of wrongdoing in the above categories.

It is important that whistle-blowers are managed in line with guidance that supports the relevant legislation and in these situations advice should be obtained from the NFCU by email.

2.2 Escalation triggers and process

2.2.1 When to escalate

The below can be used to assist you in determining which complaint, issue or incident should be escalated to the Incidents Team:

Hazard Factor – Harm to Individuals:

- There is a potential big impact on health - this issue can make people severely ill, cause death or lead to long term health impairment.

- There is potential for other types of consumer harm - for example, big financial loss or public distress/shock/disgust.

- in terms of Health Protection of vulnerable consumers, this is potentially a widespread issue which could affect large numbers of vulnerable customers.

Perception – Public views on detriment (public and media):

- This type of incident could lead to:

- national media reporting and/or

- large scale loss of consumer confidence

Scale – Number of products affected / number of people affected:

- Is the incident on a national, European or international scale?

- Is the issue widespread or has the potential to become widespread?

Integrity – Potential for food chain breakdown – crime/fraud:

- Are there suspected breaches in the supply chain integrity on a broad scale and/or evidence of widespread organised criminal activity?

History – Based on previous experience:

- This type of incident cannot be dealt with at a local level using field operational resources and procedures (Unannounced Meat Hygiene Inspector, Field Veterinary Coordinator, Official Veterinarian).

- Updated [There is limited previous knowledge of this issue.]

- This is an area where there is existing public concern and lack of confidence.

Other Government Department (OGD) Involvement:

- It does look like a complex issue in which OGDs are already, or are likely to be, involved in (even if FSA is not the obvious lead).

Where you identify a need to escalate you should do so in accordance with the lines of communication (see topic 1.4 on Lines of communication).

2.2.2 How to escalate a complaint, issue or incident

The FVC plays a key role in the handling procedure. CSU and other parts of the FSA pass food safety complaints, issues and incidents to the FVCs to co-ordinate a response.

The FVC will ultimately be responsible for deciding which complaints, issues or incidents should be escalated to the Incidents Team and for making that contact.

For other Field Operations staff:

- If after considering the escalation triggers (see sub-section topic 2.2.1 'When to escalate') the complaint, issue or incident meets the criteria for escalation to the Incidents Team, discuss this with the FVC as soon as possible.

- If, having reviewed the triggers above, there is still uncertainty whether the complaint, issue or incident should be escalated, contact the FVC who can provide advice.

- In the absence of the FVC, any issues that would fall within the incident’s definition (see sub-section 1.3 on Definition) or the escalation triggers (see sub-section topic 2.2.1 on When to escalate) should be reported directly to the Incidents Team.

On receipt of notification of an incident from the FVC, the Incidents Team will co-ordinate the Agency’s response.

Field Operations will have a key role to play in contributing to investigations and supporting the Incidents Team in delivering the response. The FSA Incident Management Plan outlines the Agency’s procedures for delivering its responsibilities in response to non-routine food or feed-related incidents.

Updated [The Incidents Team will seek Risk Management Advice (RMA) from the relevant Policy Team. Information required to inform the RMA includes:

- Product name;

- Batch Details;

- Durability indication (use by date, kill date etc);

- Quantity affected;

- Distribution (including international distribution);

- Food Chain Information;

- Other information.]

3. Annexes

Note: These pages can only be accessed by FSA staff on FSA devices.

Revision log

Published: 22 November 2021

Last updated: 9 September 2024