Understanding the international provision of allergen information picture in the non-prepacked sector

Our rapid evidence assessment aimed to develop an understanding of the international provision of allergen information in the non-prepacked food sector to develop recommendations for the FSA to inform future policy and regulation decisions based on evidence of ‘what works’.

Our rapid evidence assessment aimed to develop an understanding of the international provision of allergen information in the non-prepacked food sector. A mixed-methods approach was used, including a rapid literature and data review, stakeholder interviews, as well as co-production panel review with our advisor (Dr Audrey DunnGalvin) and members of Allergy UK and the FSA.

We found legislation on nine of the 18 countries within the scope for this project. These included three EU countries who have also brought in additional national requirements to EU legislation (Lithuania, Republic of Ireland, and Netherlands); two non-EU countries that align to EU legislation and have additional legislation in place (Switzerland, and Norway); three non-European countries (US, Philippines, and Canada) have legislation in place or draft form; and the UK. While legislation was not found in English for the other countries, all 27 EU member states follow the EU legislation as a minimum requirement. The UK follows EU legislation as we were a member state at the time of implementation. The UK has since left the EU; however the legislation has been retained. The UK has additional legislation for food that is prepacked for direct sale (PPDS), but not other types of non-prepacked food. There is considerable variation across countries and regions, in terms of type of allergens and foods covered, the required format of provision of allergen information (e.g., verbal or written) and the food establishments included within the legislation. Across all countries included within the review, the use of precautionary allergen labelling was voluntary.

The overall objective of this rapid evidence assessment was to develop recommendations for the FSA to inform future policy and regulation decisions based on evidence of ‘what works’. However, the reviewed literature provided no evidence of whether approaches are associated with improved safety, compliance, unintended consequences, or feasibility. We were also unable to infer effectiveness via data on reported trends in deaths or incidents pre and post implementation of legislation, as these data was not found for any country. Similarly, there was not enough evidence to allow a systematic analysis of incidents associated with different types or categories of food business operators (FBOs) selling non-prepacked foods. We are therefore unable to provide clear recommendations of ‘what works’ from the evidence. We have instead gathered information on the ideas or potential solutions suggested in the literature.

Introduction

RSM UK Consulting LLP (RSM) along with Dr Audrey DunnGalvin at University College Cork Consulting and members of Allergy UK, have been commissioned by the Food Standards Agency (FSA) to carry out a rapid evidence assessment into the international provision of allergen information associated with the sale of non-prepacked food. The aim of this review is to synthesise and summarise the evidence base, evaluating the current understanding of the international provision of allergen information in the non-prepacked sector. This research serves to support FSA and inform policy development and guidance in this area.

Methodology

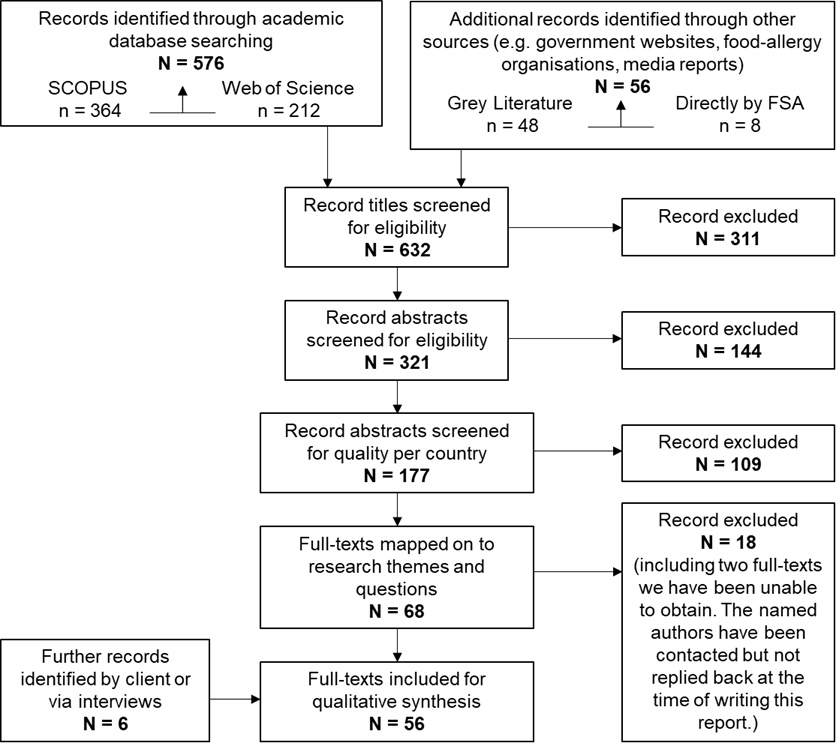

To undertake this rapid evidence assessment, we first developed a search protocol to guide the literature search. On the basis of this, we searched for relevant academic and grey literature across all 18 countries within scope. A longlist of records was screened at title (N = 636) and abstracts of the included titles (N = 321) using the second-level inclusion and exclusion criteria in Appendix A (i.e. relevance to research questions or outcomes). This list was tested for relevance and robustness following the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) guidance for critical appraisal of evidence (footnote 1) and resulted in a shortlist of 56 articles for full extraction and narrative synthesis for each research question.

We also sought to fill gaps in the reviewed literature and further develop our understanding of areas covered by the literature, and therefore we conducted 13 stakeholder interviews. Two workshops were undertaken with our panel including our academic advisor and representatives from Allergy UK, and FSA stakeholders. Conclusions, evidence gaps and areas for future consideration were triangulated across research themes.

Findings

There was limited or no evidence in the literature reviewed as to whether approaches are associated with improved safety, compliance, unintended consequences or feasibility. Table 1 provides a summary of key findings that address the study themes. We are conscious that much change is taking place in this area on an ongoing basis (with published literature not always being up to date with these developments) and this should be kept in mind when reading this report.

Table 1 Key findings to address study themes

| Results theme | Findings |

|---|---|

| Non-prepacked sector legislation |

|

| Trends in related deaths or incidents |

|

| Enforcement process and capabilities |

|

| Consequences of non-compliance |

|

| What works, for whom and why |

|

Considerations for further research

The literature reviewed does not provide evidence of ‘what works’ for different approaches, for example in terms of improved safety, compliance, unintended consequences, or feasibility. This means that we are unable to provide clear recommendations for FSA.

We have instead gathered information on the ‘problems raised in the research’ including the challenge for inspectors to verify verbal information, the level of confidence amongst consumers with the verbal information provided by food businesses, the gap in awareness or understanding related to food allergies amongst staff and inconsistency in the interpretation and use of PAL by businesses and consumers alike.

There were suggestions in the evidence on what may work including:

- Increasing or improving the written provision of allergen information (footnote 9) (footnote 10)

- Standardisation of information provision, for example in terms of placement of allergen information and use of symbols (footnote 11) (footnote 12)

- Introducing best practice or regulation for PAL and improving education for all stakeholders regarding interpretation and use of precautionary labelling (footnote 13)

- Address the potential resourcing gap faced by enforcement authorities (footnote 14)

- Better opportunities for food allergen training, particularly if self-paced, with real world examples and simple language (footnote 15) (footnote 16)

The above is not an exhaustive list of potential options to consider, and further research is required to develop other options. Further systematic reviews, evaluations or feasibility studies would be required before any potential solution is implemented.

It is important to also note that the strength of the evidence underlying the problems and potential solutions identified in this report from the reviewed literature varied, ranging from news reports, conference papers, published audits, official legislation and peer-reviewed academic literature with large mixed-method studies and systematic reviews.

-

DEFRA (2015) Production_of_quick_scoping_reviews_and_rapid_evidence_assessments.pdf (publishing.service.gov.uk)

-

New Zealand: Speakman, S., Kool, B., Sinclair, J. & Fitzharris, P., 2018. Paediatric food-induced anaphylaxis hospital presentations in New Zealand. J Paediatr Child Health, Issue 54, pp. 254-259.

US: Chaaban, M. R. et al., 2019. Epidemiology and trends of anaphylaxis in the United States, 2004-2016. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol., Issue 9, p. 607– 614.

UK: Wells, R. et al., 2022. National Survey of United Kingdom Paediatric Allergy Services. Clinical & Experimental Allergy, 52(11), p. 1276–1290

-

DunnGalvin, A., Roberts, G., Regent, L., Austin, M., Kenna, F., Schnadt, S., Sanchez‐Sanz, A., Hernandez, P., Hjorth, B., Fernandez‐Rivas, M. and Taylor, S., 2019. Understanding how consumers with food allergies make decisions based on precautionary labelling. Clinical & Experimental Allergy, 49(11), pp.1446-1454.

-

Eisenblätter, J., Schumacher, G., Hirt, M. et al. How do food businesses provide information on allergens in non-prepacked foods? A cross-sectional survey in Switzerland. Allergo J Int 31, 43–50 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40629-021-00191-5

-

Food Safety Authority of Ireland. Targeted Audit of Allergen Information of Non-prepacked Food. (2017).

-

Food Safety News. Dutch control finds gaps in allergen information given to consumers (2022).

-

Republic of Philippines, Act mandating the disclosure of food allergens in products offered by food establishments and for other purposes, (2022).

-

Begen, Fiona M., Julie Barnett, Ros Payne, Debbie Roy, M. Hazel Gowland, and Jane S. Lucas. "Consumer preferences for written and oral information about allergens when eating out." PloS one 11, no. 5 (2016): e0156073.

-

Marra, C.A., Harvard, S., Grubisic, M., Galo, J., Clarke, A., Elliott, S. and Lynd, L.D., 2017. Consumer preferences for food allergen labeling. Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology, 13, pp.1-11.

-

Republic of Philippines, Act mandating the disclosure of food allergens in products offered by food establishments and for other purposes, (2022).

-

Begen, Fiona M., Julie Barnett, Ros Payne, Debbie Roy, M. Hazel Gowland, and Jane S. Lucas. "Consumer preferences for written and oral information about allergens when eating out." PloS one 11, no. 5 (2016): e0156073.

-

Madsen, C.B., van den Dungen, M.W., Cochrane, S., Houben, G.F., Knibb, R.C., Knulst, A.C., Ronsmans, S., Yarham, R.A., Schnadt, S., Turner, P.J. and Baumert, J., 2020. Can we define a level of protection for allergic consumers that everyone can accept?. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, 117, p.104751

-

Based on qualitative interviews we conducted in this study

-

Soon, J.M., 2020. ‘Food allergy? Ask before you eat’: Current food allergy training and future training needs in food services. Food Control, 112, p.107129.

-

Lee, Y.M. and Sozen, E., 2016. Food allergy knowledge and training among restaurant employees. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 57, pp.52-59

RSM UK Consulting LLP (RSM), working in partnership with University College Cork Consulting and Allergy UK, were commissioned (6 December 2022) by the Food Standards Agency (FSA) to carry out a rapid evidence assessment to develop an understanding of the international provision of allergen information in the non-prepacked sector.

Food hypersensitivities (FHS) have a severe and enduring psycho-social impact on people with the condition (Begen, et al., 2016). Previous research has found that households with FHS bear a greater economic and financial burden, spending up to 17% more on weekly food purchases as well as losing a week off work (paid and unpaid) due to their condition (RSM, 2022). As such, it is crucial that consumers with FHS are provided with, or can access, consistent and accurate information about food allergens contained within products they purchase and consume.

- In December 2014, the Food Information for Consumers (FIC) Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011, extended the existing requirement to declare 14 mandated allergens on prepacked food to include non-prepacked/loose food (e.g. food sold loose, food packed on premises at the request of the consumer, meals served in a restaurant).

Study aims

This study aimed to:

- determine the legislated approaches for the provision of food allergen information in the non-prepacked sector across 18 countries

- understand trends in allergy-related deaths and incidents data across these countries

- gather information on the enforcement process and capabilities in each country

- review the consequences for non-compliance, monetary or otherwise, applicable in each country and their effectiveness

- understand ‘what works’ from four categories of stakeholders, including consumers, researchers, policymakers/ enforcement authorities, and food businesses.

These aims provided the high-level themes that were used to guide the evidence collection, analysis and reporting.

A note on recommendations from the research: The overall objective of this rapid evidence assessment was to develop recommendations for the FSA to inform future policy and regulation decisions based on evidence of ‘what works’. However, the literature reviewed, provided limited evidence on the effectiveness of policies, i.e. evidence which evaluated the approaches relating to measures such as improved safety, compliance, unintended consequences or feasibility. As such, we were unable to provide evidence-based recommendations from the literature reviewed. We have instead gathered information on the ideas or potential solutions suggested in the research. However, we would caution the reader about implementing these without a systematic review and evaluation of the effectiveness, feasibility and disbenefits associated with these and other potential solutions.

A mixed-methods approach was used to deliver this project, including a rapid evidence assessment for our literature and data review, and fieldwork to conduct stakeholder interviews, as well as a co-production panel review with our advisor and members of Allergy UK and the FSA. The project was divided into three work-packages, as follows:

- searching, screening and extracting of information from the literature to trace legislation and trends in deaths and incident data per country (section 4.1)

- Conducting fieldwork with stakeholders through one-to-one interviews to consolidate on findings and gaps from the literature review (section 4.2)

- synthesising, triangulating, and reporting evidence into a final report (section 4.3)

There were 18 countries within scope for this work, including UK, Republic of Ireland, Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark, Norway, Germany, Lithuania, Sweden, Switzerland, Australia, Canada, India, Malta, New Zealand, Philippines, South Africa, and US. However, depending on the geography covered by the literature, we extended this to also include the EU and global region.

4.1 Literature search, screening and data extraction

A literature search was performed using several strategies, including:

- purposive searches (footnote 1) of legislation, data registries for food allergy related deaths and incidents, unpublished studies, evaluations, and media reports using the search terms in Appendix A

- a targeted search (as per the search terms in Appendix B) of two academic databases - Web of Science and SCOPUS

- a call for evidence amongst our FSA panel of experts and advisors

Figure 1 PRISMA style reporting of records at each stage of screening

Altogether, the searches resulting a longlist of N = 632 titles which were rigorously screened as detailed in Figure 1. This resulted in a shortlist of 56 articles as listed in Appendix C. At each stage, two reviewers were involved in screening and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus development.

4.2 Interviews

13 interviews were conducted with national and international stakeholders to consolidate findings from the literature review. We had two objectives for interviews – to build upon literature review findings and to address gaps in the literature. The interviews were conducted remotely on a one-to-one basis via Microsoft Teams. These included stakeholders from four categories: (a) consumers with FHS and patient advocates, (b) academic researchers working within the field of FHS, (c) enforcement authorities or policymakers, and (d) FBOs and trade bodies. Table 2 provides information on the number of interviewees per category as well the country they represented. We had difficulties recruiting interview participants specifically from enforcement officers outside of the UK and FBOs within or beyond the UK, despite a large outreach attempt through emails sent via RSM, FSA and our advisors as detailed in Table 2. For the topic guides used to facilitate the interviews, please see Appendix D.

Table 2 Mapping of interviewees in terms of their categories and countries

| Stakeholder category | N (out of target) | Country | Estimated outreach attempt |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer with FHS, patient advocates | 4 out of 4 | UK Sweden Germany India |

7 (Germany, India, South Africa, Sweden, UK) |

| Researcher | 3 out of 3 | Spain/EU US |

4 (EU, South Africa, Spain, US) |

| Enforcement/ policy | 5 out of 4 | UK only | 50 (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Philippines, UK, US) |

| Food business organisations and trade bodies | 1 out of 4 | UK only | 78 (Belgium, Denmark, EU, Germany, India, Norway, Sweden, UK, US) |

4.3 Analysis and reporting

Findings from the literature review and interviews were triangulated and summarised, guided by the five themes of this research based on the study aims:

- Non-prepacked legislation

- Trends in related deaths or incidents

- Enforcement process and capabilities

- Consequences of non-compliance

- What works (or may work) for whom and why

5.1 Current legislation or best practice guidance

Summary of key findings

- We found legislation on nine of the 18 countries within the scope for this project. These included three EU countries who have also brought in national requirements additional to EU legislation (Lithuania, Republic of Ireland, and Netherlands); two non-EU countries that align to EU legislation and have additional legislation in place (Switzerland and Norway); three non-European countries (US, Philippines, and Canada); and also the UK.

- Legislation provision varies across countries/ regions with five mandating written provision (Republic of Ireland, Lithuania, Norway, US and Canada), and in four regions/countries either written or verbal provision is accepted (Netherlands, Switzerland, UK as well as EU-wide except the countries mentioned earlier).

- No relevant legislation or guidance was found in English in Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Sweden, Australia, India, Malta, New Zealand, South Africa. However, the 27 EU countries follow EU legislation as a minimum requirement, which would apply to Denmark, Belgium, Germany, Malta and Sweden.

Legislation provision was available in English for nine of the 18 countries within scope. The legislation is varied in terms of the establishments included, provision of information and the allergens covered. Across all 18 countries/ regions within scope, the provision of PAL is voluntary. A full breakdown of the legislative requirements for each country can be found below. The evidence presented in this chapter is based on legislation by each government and/or evidence found through our rapid evidence assessment.

EU member states non-prepacked food legislation provision

EU legislation was introduced in December 2014 under the Food Information for Consumers (FIC) Regulation No 1169/2011 (European Parliament, 2014). Legislation was introduced after a study found that 70% of severe allergic reactions occurred after eating non-prepacked foods (reported in the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Public Declaration 7 in 2013, as cited in Reed, 2018). The purpose of the legislation is to ensure that people who have food hypersensitivities are provided with clearer information regarding allergenic ingredients (Begen et al., 2017).

This legislation applies to the provision of information for non-prepacked foods, requiring providers to supply information relating to the presence of any of the 14 mandatory allergens in any dish. This information must be provided in all establishments selling non-prepacked foods including, but not exclusive to, restaurants, takeaway shops, food stalls, institutions like prisons and nursing homes as well as workplace and school canteens. The business has flexibility in how they provide allergen information to consumers. This information could be provided through displaying allergen information on a chalkboard, menu, in an information pack or orally. However, if information is provided orally the food business must tell consumers where this information can be obtained e.g. by using a written notice placed clearly in a visible position asking consumers to speak to staff if they have food allergies, intolerances or coeliac disease (European Parliament, 2014).

This applies to all 27 EU countries including the following countries within scope for this project: Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Malta and Sweden. A few member states of the EU have additional measures as outlined below.

EU member states with additional non-prepacked food legislation

Republic of Ireland

The Republic of Ireland follows EU Regulation No 1169/2011 but has also brought in national legislation under the Statutory Instrument (SI) No. 489/2014 - Health (Provision of Food Allergen Information to Consumers in respect of Non-Prepacked Food) Regulations 2014. The Food Safety Authority Ireland introduced the additional SI following an online consultation during 2013 on behalf of the Department of Health to determine the views of stakeholders on how best to declare the use of the 14 regulated food allergens in the manufacturing or preparation of non-prepacked foods (Food Safety Authority Ireland, 2014).

The additional SI regulations apply to all food which is not prepacked, which is offered for sale or supply. This requires all food businesses, e.g., restaurants, delis, canteens, public houses, takeaways, or retail outlets, under the SI to supply specific minimum requirements of written allergen information that must be provided at either the point of presentation, point of sale or point of supply. This information should be freely available without the customer needing to ask for it and must be easily located and accessible before the sale or supply of the food - customers must have the information before buying and must not have to ask for the information. FBOs have flexibility on how information is provided for example, numbers or symbols on a menu, an allergen folder on a counter, through an allergen matrix on the wall or a label next to the food (Food Safety Authority Ireland, 2014).

Republic of Lithuania

The Republic of Lithuania follows EU Regulation No 1169/2011 but has brought in an Amendment to Directive number 677 HN 119:2014 'Food product labelling' 2016. (footnote 1) This amendment specifies that information on food allergens that are stated in EU legislation must be provided for non-prepacked food sold in retail establishments, vending machines, or automated retail establishments in line with the requirements under EU regulations.

Information on non-prepacked foods must be provided in writing or by electronic means, through scanning the barcode. This information must be visible, easy to read and available before food is purchased. Where a price label is displayed, information can be provided on the same label in written format. If there is no price label, allergens must be listed on the product or shared electronically. Additionally, if consumers are asked about their food hypersensitivities before ordering/ purchasing food and if the information is available in writing or electronic means to the person providing the food directly to the consumer [e.g., a waiter], then it is not mandatory to provide additional/ further written information to the consumer. (Republic of Lithuania, 2016).

Netherlands

Dutch regulations require food businesses to provide information on the presence of any of the 14 mandated allergens in the food they are selling. Food businesses can provide this information in writing e.g. on a menu or a label next to the food, or verbally. If verbal information is provided, there must be a clearly visible sign advising consumers how allergen information can be requested.

In addition to the EU allergen information requirements set out in EU regulation No 1169/2011, national rules apply in the Netherlands. If information is provided verbally then it must be available to the consumer without delay. Allergen information must also be available in writing or digitally for staff and inspectors (Hoogenraad, 2014).

Non-EU countries aligning to EU non-prepacked food legislation

Norway

Regulation on food information for consumers (The Food Information Regulation) 2014 was introduced in Norway as supplementary provisions to the adopted EU Regulation No 1169/2011 (Government of Norway, 2014).

All FBOs must provide allergen information to the consumer in writing, for example the information can be given on the menu, or on a notice, screen or poster. FBO employees are also required to have knowledge of which allergens are contained within food. Additionally, supermarkets must provide written allergy information for non-prepacked foods to consumers. Temporary events (school fetes) are excluded from being required to provide allergen information for non-prepacked foods (Government of Norway, 2014).

Switzerland

Swiss Food Law Art 5, IO 2017 places responsibility on food businesses (staff or well-informed person) selling non-prepacked food to provide allergen and intolerance information to consumers at point of first contact. Information can be provided in written format or verbally to consumers. The provision of verbal information is on the condition that a written note on how to obtain information is provided, and someone can provide this information accurately. Verbal information can then be either given based on written documentation or by an informed person. The new revision was brought in to align Swiss food law more closely with EU regulations (Eisenblätter et al., 2022).

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom currently follows retained EU law for non-prepacked foods, under EU Regulation No 1169/2011.

Non-European countries non-prepacked food legislation

Canada

In Canada some non-prepacked foods require labelling, under the Food and Drug Regulations 2009, last amended December 2022 (Government of Canada, 2009). T Labelling requirements include a list of ingredients including the presence of food allergens. (Government of Canada, 2022). From the legislation reviewed, allergens covered were not listed, but the priority allergens in Canada include eggs, milk, mustard, peanuts, crustaceans and molluscs, fish, sesame seeds, soy, sulphites, tree nuts, wheat and triticale (Government of Canada, 2020).

Philippines

Although pending with the Committee on Health since 6 September 2022, the Philippines have drafted the Food Allergen Disclosure Act mandating the disclosure of food allergens in products offered by food establishments and for other purposes (not defined in the legislation). This Act would mandate written provision of allergen information for food establishments to identify food allergens in line with the allergen list published by the Food and Drug Administration in every menu item. Exempted from provision are carinderias (food stalls with small seating areas), backyard food stalls, walking food vendors, food kiosks, and other similar businesses (Republic of Philippines, 2022).

United States

In the United States, three states - Massachusetts, Maryland, and Rhode Island - have food laws in place for restaurants relating to allergies (Food and Drug Authority allergen list is not specified in legislation): The legislation for these three states has been summarised in the table below.

Table 3 United States legislation

| State | Legislation | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Massachusetts | Massachusetts Food Allergy Awareness Act 2009 | Restaurants are required to display a Department of Public Health approved food allergy awareness poster in staff areas. Restaurants must also display a notice to customers on menus of the customers obligation to inform staff about food allergies. A Certified Food Protection Manager must be employed at each restaurant and must have undergone allergy training, certificated by the Department of Public Health (Massachusetts State 2009). |

| Maryland | Maryland Code Annotated, Health-General 21-330.2(A) | Maryland State law requires a food establishment to prominently display a poster in staff areas. The poster relating to allergy awareness must include information on the risks of allergic reactions (Maryland State Government 2014). |

| Rhode Island | Rhode Island Allergy Awareness in Restaurants Act in 2012 | Similarly, to Massachusetts, Rhode Island requires restaurants to display an approved food allergy awareness poster in staff areas. A notice must also be included on menus of the customers obligation to inform staff of their food allergies. A designated Food Protection Manager must review written and video materials and be certified by a food protection manager certification program (Rhode Island State 2012). |

5.2 Trends in data for deaths or hospitalisations

Summary of key findings

- The number of food allergy related reactions or hospitalisations appear to be rising worldwide, as evidenced in Denmark, New Zealand, South Africa, and USA.

- Due to limited data, we were unable to identify or report trends in deaths or incidents pre and post implementation of legislation, in any country. Similarly, there was not enough evidence to allow a systematic analysis of incidents associated with different types or categories of FBOs selling non-prepacked foods.

- There are geographical differences in the allergens known to trigger anaphylaxis reactions, based on the most commonly available food sources in that region.

Challenge: Gaps in the available data (deaths/hospitalisations), and barriers to reliable reporting There were no sources of longitudinal, systematic deaths/hospitalisations data related to food allergies in the non-prepacked sector, either in the UK or internationally. There is also heterogeneity in the methods used and a lack of agreement on what is best practice in terms of data collection and harmonisation of what constitutes anaphylaxis. This gap operates as a barrier to identifying and/or reporting any trends in deaths, reactions, and hospitalisations pre and post the implementation of legislation in any specific country. There was also limited evidence on any associations between deaths or allergic reactions and the categories or characteristics of FBOs selling non-prepacked foods that may be responsible for reactions. This gap operates as a major barrier for any systematic evaluation of effectiveness of allergen information provision.

Potential solution: For both such barriers, primary research is required to develop registries or other suitable tools to gather relevant data on allergic reactions, hospitalisations and/or deaths. This could involve providing support and incentives for developing registries and harmonized methods in defining and recording of anaphylaxis and categorisation of FBOs selling non-prepacked foods.

5.2.1 Global trends in food allergy related deaths or hospitalisations

A literature search for food allergy related death or hospitalisation data worldwide has demonstrated that reported data is limited, with some areas having very limited information available and data specific to non-prepacked food incidents almost non-existent. Moreover, the majority of literature available on this topic is focused on children, excluding adults and the elderly – most likely due to higher prevalence of food allergies in children compared to other segments of the population. As such, we were unable to identify or report trends in deaths pre and post the implementation of legislation in any country.

Existing literature suggests that the number of food allergy related incidents is increasing across the world. A recent analysis of public hospital discharge data for children aged 0-14 years in New Zealand found that the annual food-induced anaphylaxis hospital presentation rate increased almost three-fold between 2006 (8.4 per 100,000 children) and 2015 (24.0 per 100,000 children) (Speakman, et al., 2018). A similar trend was reported for the USA, where a retrospective study explored a commercial insurance claims database and found that food-related anaphylaxis incidents in children and adults had increased by 177% between 2004 (incidence rate of 86.3 per 1000 person-years) and 2016 (239.2 per 1000 person-years) (Chaaban, et al., 2019). Additionally, the prevalence of all types of allergies (including food allergy) in children appears to be increasing in the UK, demonstrated by an approximate sevenfold increase in new allergy appointment capacity from 2006 to 2020 to meet the growing demand (Wells, et al., 2022).

For the most common causes of anaphylaxis, an investigation of children presenting to a single hospital in South Africa between January 2014 and August 2016 found that food-related triggers caused 152 out of the 156 cases (Chippendale, et al., 2022). A single-hospital study in Denmark found similar results for children, with 14 out of 23 cases associated with a food-related trigger (Oropeza, et al., 2017).

5.2.2 Regional differences in food-related anaphylaxis triggers and their influence on local legislation

A recent systematic review found that peanut, cow’s milk and crustacean (water animals with a hard shell – e.g. crab, lobster, shrimp) allergies were amongst the most common causes of food-related anaphylaxis cases worldwide (Baseggio Conrado, et al., 2021). This review explored anaphylaxis links to specific food triggers using data for food-related incidents from 41 countries, across six regions (Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America/Caribbean, Near East and North America and the Southwest Pacific). The reviewers found some notable geographical differences. As an example, anaphylaxis triggered by wheat was shown to account for a high proportion of cases in China (37% of regional referrals (footnote 2)) but generally accounted for a smaller proportion of cases in Europe, North America and the Southwest Pacific regions. Furthermore, crustaceans were responsible for a disproportionately high number of anaphylaxis cases in adults in Europe, North America, Southwest Pacific and Asia (data for other areas not available). Cow’s milk was responsible for a high number of paediatric presentations in Europe and Asia. The authors reported that food allergens known to cause a significant proportion of anaphylaxis cases in a particular region were more likely to be covered by local laws requiring their disclosure to the consumer.

Although this review relied on real-world data to identify the most common causes of food-related incidents, more information is needed to robustly identify global trends. From this we have identified two main barriers to the collection of reliable and comparable data. Firstly, there is a significant lack of data for most of the regions investigated. Secondly, there is a lack of agreement on the methods used to define and record anaphylactic reactions.

5.2.3 Potential link between types of food business and food allergy related incidents

We explored the literature for any potential associations between the characteristics or types of FBOs selling non-prepacked food and resulting food allergy related incidents. However, there was not enough information to assess such correlations in the countries discussed, as most publications reviewed either do not include the data for the entire population or the results cannot be generalised to the wider population due to methodological constraints. We did find some relevant findings, which are briefly outlined here.

A study from South Africa, which examined 156 anaphylactic reactions in children, found that 41% were related to non-prepacked foods compared with 56% were related to non-prepacked foods (Chippendale, et al., 2022). The triggers in the remaining 3% of the cases reported in this study were unknown. A cross-sectional survey of adults with food allergy over nine months in Australia found that 27% of the respondents reported an anaphylactic reaction due to consuming food from a variety of food venues. Of these, 39% were restaurants, 25% cafés, with the remaining takeaways, bakeries, etc. (Zurzolo, et al., 2021). A mixed-methods study in Berlin, Germany with parents of children with food allergies, reported that 42% reported an allergic reaction to a non-prepacked food. Of these, 25% had purchased the food which triggered a reaction from a bakery, 20% from an ice cream parlour, 14% from a restaurant and 17% from other establishments (supermarket, school, café, etc) (Trendelenburg, et al., 2015). This study only compared cases across different non-prepacked FBOs and did not provide equivalent data for cases associated with prepacked foods.

5.3 Enforcement processes and capabilities

Summary of key findings

- There was limited evidence regarding enforcement processes and capacity across the 18 within-scope countries and regions.

- Our interviews with enforcement authorities in the UK (n=5) suggested that enforcement capacity is an important challenge, with food hygiene checking prioritised over food allergen labelling.

- Our interviewees from the US (n=2) and Germany (n=1) also suggested that the approach to enforcement may be regionally inconsistent due to the federal system within their countries.

- The literature found that for those FBOs voluntarily using PAL, the application and use can be challenging as it is inconsistently interpreted and applied by food businesses.

Our research aimed to gather information on enforcement processes and capabilities, in addition to the training and qualification requirements for enforcement officers across the countries within scope. However, there was limited information available for review. Furthermore, we were unable to recruit enforcement authorities outside of the UK for interview despite reaching out to 50 enforcement teams across six countries. Here we briefly outline those findings we were able to garner on enforcement and training from:

a) Reviewed literature: The approach to enforcement in the UK and the Netherlands (based on the Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority, NVWA; as reported by Food Safety News, 2022) is to guide and support the food business before taking any action against them. If an inspector finds a problem, a warning is handed to the business, and it is given time to remedy the issue. However, if the business continues to be in violation of the regulation, a fine is then imposed.

b) Interviews: the main themes to emerge from the interviews were: processes of enforcement and enforcement capacity.

In terms of the enforcement process, an interview with a patient advocate in Germany suggested a high level of diversity and inconsistency in enforcement processes across the federal states.

“Our [German] food inspection system is a federal one, so each state [has] their own [enforcement process], and you can see that the way allergen information is dealt with [is] quite diverse. There are some states who have a focus on full diligence, and they do quite a lot they also publish yearly reports when they do their food inspection.”

- Patient advocate, Germany

Interviews with stakeholders in both the UK (n=5) and the US (n=2) highlighted that enforcement capacity and funding are key challenges for them, with one US-based researcher suggesting that hygiene inspections were given more priority over allergen-related monitoring of menus. This was also echoed in an interview with a UK-based enforcement officer who said that food safety (including hygiene) was checked more regularly and consistently than food standards (such as allergen labelling and information).

“Restaurants and food service facilities are regulated by state, municipal or tribal organisations. They are typically poorly funded and don’t have a lot of resources to inspect restaurants. Inspectors are probably more trained in how to spot insanitary conditions but wouldn’t need considerable additional training in order to monitor menu labelling.’

- Researcher, US

5.4 Non-compliance and its consequences

Summary of key findings

- There is a large variation in the published rates of non-compliance across countries, ranging from 14% in Switzerland (in 2022) to 88% in Ireland (in 2017).

- There is little evidence on the consequences that FBOs have faced for non-compliance. The available evidence showed that in three countries reported below, non-complying FBOs tend to face fines and/or are issued with written warnings.

- A number of strategies have been suggested that may improve compliance, including providing more training opportunities for FBO staff, improving reporting systems and more timely enforcement actions.

Our research aimed to gather data on the compliance rates internationally across the countries within-scope, as well as on the consequences for non-compliance and their relative effectiveness. We also aimed to collect information on what actions could be taken to improve compliance and assess how many businesses that are reported end up facing consequences. However, there was limited information gathered from the reviewed literature and we also were unable to recruit enforcement authorities outside the UK for qualitative interviews. Below, we summarise the limited, discrete findings related to compliance and consequences faced by businesses for not complying with relevant legislation.

Rates of compliance across multiple countries

In 2021, the Netherlands Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority (NVWA) inspected more than 5,000 companies to see if they complied with the legislation for providing allergen information on non-prepacked goods (as reported by Food Safety News, 2022). In this inspection, the authorities found that 62% of restaurants, hotels and cafeterias were non-compliant (i.e. 2,000 out of 3,200 establishments). Further, 50% of artisan producers such as bakeries and ice cream shops were non-compliant (i.e., 955 out of 1,910 producers). Finally, 40% of the retailers such as supermarkets were non-compliant (i.e., 191 out of 471 retailers).

The Food Safety Authority of Ireland in 2017 conducted a targeted audit of 50 premises selling non-prepacked foods. The inspection found that 32% of FBOs did not provide any allergen information for the food prepared and sold in their establishments (i.e. 16 out of 50). Further, out of the 34 FBOs that provided allergen information, 76% had inaccurate allergen information (i.e. 26 out of 34) and 62% provided information in writing in line with the legislation (i.e. 21 out of 34). Finally, 8% of the FBOs that provided distance selling services were not compliant with the legislation requirements (i.e. 1 out of 13). Overall, the authorities found that 88% of the inspected FBOs were required to undertake corrective actions (i.e. 44 out of 50 FBOs).

The Swedish National Food Agency in 2022 conducted a coordinated control project to verify the allergen information provided to consumers in restaurants and cafes with 71 municipal authorities involved. A total of 2,172 businesses and 4,344 products were tested. The authorities found that 25% of the inspected FBOs provided incorrect allergen information (i.e. 543 out of 2,172 FBOs). They also inspected products at these establishments and found that 17% of the sampled products had labels with incorrect allergen information (i.e., 738 out of 4,344 products).

Eisenblätter and colleagues undertook a telephone survey with FBOs selling non-prepacked foods in Switzerland in 2019 (Eisenblätter et al., 2022) and found that 86% provided oral allergen information and only 14% provided written information, either upfront or on request. Importantly, about 41% of the surveyed FBOs (who did not provide written information upfront) reported that they do not provide a written notice on how to access allergen information, even though it was a legal requirement (i.e. 146 out of 349 FBOs). This non-compliance varied with type of business, ranging from 16% in restaurants, to 37% in butcher shops, 60% in bakeries/ patisseries and 57% in dairy shops.

Trendelenburg and colleagues undertook similar research in Germany in 2013 (Trendelenburg et al., 2015). They sampled and tested 73 non-prepacked products sold by bakeries as ‘cow’s milk free’. The tests showed that cow’s milk was detectable in 43% of these products that were recommended by the staff as free from cow’s milk (i.e., 31 out of 73 products).

Consequences for non-compliance

There is little information available on the consequences that FBOs face for non-compliance in the published literature. One example from the Netherlands suggests that written warnings are commonly used, with the Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority (NVWA) issuing nearly 3,400 written warnings in 2021 (Food Safety News, 2022). Additionally, fines are commonly applied if FBOs do not comply with the legislation, with data suggesting that the NVWA in the same year had issued 591 fines of €525 (£463). A publication from Ireland suggests that non-complying FBOs may face consequences such as ‘an order for costs and expenses in addition to, and not instead of, any fine or penalty a court may impose’ (Food Safety Authority Ireland, 2014). Further, the Republic of Philippines proposed that non-complying businesses would be fined between 50,000 PHP (£750) to 100,000 PHP (£1500) although the bill is yet to be enacted into a law (Republic of Philippines, 2022).

We did not find any published evaluations on the effectiveness of these consequences, or investigations of the enablers and barriers for compliance. Our literature review and qualitative fieldwork offer two insights into possible reasons underlying non-compliance: type of FBOs and FBO staff awareness and understanding of food allergens.

Two UK-based enforcement officers shared that in their experience, smaller or less organised FBOs were less knowledgeable and more likely to encounter issues with the provision of allergen information. A systematic analysis of compliance in terms of FBO characteristics may be useful to understand factors that support or reduce compliance.

“The problems that I [mostly] encounter probably are in the takeaway service sector. I think it's because there's perhaps a lack of understanding from the food business operator keeping up to date with hygiene and safety requirements.”

- Enforcement officer, UK

Lack of awareness and understanding amongst non-complying FBOs

A targeted audit in the Republic of Ireland showed that staff in 16 out of 50 food service outlets were unaware of the legal requirements (Donovan, et al., 2018). Further, an audit conducted in Ireland (FSAI, 2017) found that businesses reported the following reasons for non-compliance:

- Lack of understanding of allergens

- Lack of understanding of the requirements of the legislation

- Lack of time to conduct an allergen assessment (and clarity on how to do so)

- Over-reliance on certain staff (e.g. head chef) to assess for allergens, while other staff unable to provide required information

Suggestions which could improve awareness

The Republic of Ireland study suggested the FBOs undertake steps to “fully inform themselves about food allergens” and “make food allergen training a central component of staff training programmes” (p.17, FSAI, 2017).

Additionally, Gowland and Walker (2015) identify a number of strategies that may improve compliance based on their analysis of eight cases related to food allergy that underwent criminal or civil prosecution in the UK. Their suggestions include the following:

- a consistent system and process to report cases centrally for a region or country

- a consistent approach and timely enforcement actions to improve compliance rates

- a ‘culture of zero tolerance for food fraud’

- to ‘accelerate [the] escalation of action against poor labelling and misleading food description when they pose an allergen risk’

- documented traceability of ingredients

5.5 What works, for whom and why?

Summary of key findings

- There was a lack of evidence in the reviewed literature assessing approaches on factors such as improved safety, compliance, unintended consequences, or feasibility. This means that we are unable to provide clear recommendations. We have instead gathered information on ‘problems raised in the evidence’ and ‘potential solutions that may work’.

- From the literature and interviews, enforcement authorities, patient groups, consumers and FBOs identified several areas which caused problems for them including: the format that allergen information is provided in, FBO staff communication and legislation perceived to be unclear.

- In highlighting what may work, literature and interviewees suggested standardisation of information provision including written provision of information, regulating PAL, and improved resources and capacity of enforcement authorities.

Our review of the literature highlighted a gap in the current evidence demonstrating ‘what works’, for example, in terms of safety, business compliance, and cost-effectiveness. Several studies included in the literature did, however, suggest problems in providing accurate allergen information or barriers faced by stakeholders such as enforcement authorities, FBOs and consumers with allergies. These studies also offered potential solutions that could address the problems or barriers they found. Based on this, the following section of this report provides a summary of problems raised for each stakeholder group, as well as potential solutions that may work as supported or suggested by the reviewed literature. Please note that the potential problems and solutions discussed here would need to be tested in further research to assess their efficacy in terms of both benefits and disbenefits, and feasibility.

5.5.1 Enforcement authorities

Format of allergen information

Problems raised in the evidence. Overall, very few publications seem to consider food allergen information provision from the perspective of enforcement authorities. However, it seems that the complex nature of non-prepacked food allergen information regulations can make enforcement and inspections of non-prepacked food businesses difficult. As highlighted by one media report (Food Safety News, 2022), an inspection by the Netherlands Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority (NVWA) found challenges associated with both written and verbal formats of information provision. In particular, the companies that gave allergen details in writing often provided this information separate from the product rather than immediately associated with the relevant products. For the companies that provided it verbally, staff were able to say which allergen was in each product, but the information was not available in writing or electronically, so inspectors found it challenging to verify.

Communication and engagement with staff

Problems raised in the evidence. Interviews with enforcement officers in the UK (n=5) highlighted a number of challenges. These included: communication between enforcement officers and FBO staff who have English as a second language, non-English speaking kitchen staff, staff turnover levels, a lack of understanding around the requirements and inconsistency in the communication of customer needs through third party apps, for example those used to aggregate orders for food delivery.

‘One of the biggest barriers is language. There's been times where I've dealt with food businesses and English isn't their first language, so I'm relying on another person coming in from the business and translating. Or you know, I've had to try and use Google Translate, so then you're not entirely sure [of the accuracy of] what's been said.’

- Trading standards officer, UK

Enforcement capacity and capabilities

Problems raised in the evidence. Enforcement officers also shared in interviews (n=5) that capacity, time and resource were also common challenges for carrying out inspections. This resource gap may have knock-on effects on the enforcement process, for instance that not all premises that need to be inspected end up being inspected in a timely way, or allergen-related checks are not completed due to higher priority placed on food hygiene checks. This can have consequences for compliance and may explain the relatively low compliance levels across most countries, although we do not have evidence on the enforcement capacity in countries other than the UK.

‘…We are very limited in the food officers that are going out. So if you come across a problem business that is taking up more of your time, that means that you're going out and doing less inspections elsewhere. If we're looking to verify that food is correct and as described with regards to the allergen information, then we've got to take samples - not only is it a cost to send these samples off for testing… it's Officers’ time inputting, collecting, arranging for collection of samples and stuff like that.’

- Enforcement Officer, UK

Suggestions of what may improve enforcement capacity and capability. In terms of enabling factors, enforcement officers shared via interviews (n=5) that they have a number of ongoing training and collaboration opportunities to share good practice and keep up to date with the latest regulations. While this does not directly resolve the capacity issue raised by enforcement officers, it may support their continuous professional development.

“[The] Knowledge Hub group which we can access from trading standards points of view has some interesting conversations…The Food Standards Agency also brought out a frequently asked question document which is quite useful to refer to as well…. We do talk as Officers, so we do meet regularly, in the team that I work in, and we do try and share examples.”

- Enforcement Officer, UK

5.5.2 Food businesses

Understanding and awareness amongst staff.

Problems raised in the evidence. A number of reviewed studies showed that a key challenge for FBOs in providing allergen information was related to the allergen-related awareness and understanding of staff. Young and Thaivalappil (2018) conducted a systematic review of international studies (including the UK) and showed that FBO staff held inaccurate beliefs in relation to food allergies, such as high heat can destroy allergens in food (about 35%) and that customers with food allergies can consume a small amount of the allergen safely (about 20%). These results mirrored those found in the FSAI 2017 audit in terms of lack of awareness and understanding associated with non-complying FBOs as reported in section 5.4. Further, Lee and Sozen (2016) found that, in a sample of 229 respondents working in the US non-prepacked food sector, found that more than half believed that milk allergy and lactose intolerance were the same and 40% were unable to identify soy and fish as major allergens. It may be useful to have more recent data to see if this is still an issue, as these reports are from five or more years ago and the situation regarding allergen knowledge may have changed since then.

Suggestions which may improve staff understanding and awareness. Together, these indicated gaps in staff knowledge and the authors suggested “increased education and training of restaurant and food service personnel” (Young & Thaivalappil, 2018, p.13; see also Donovan, et al., 2018; DunnGalvin, et al., 2015; Lee, et al., 2016). Encouragingly, evidence suggests that the willingness of staff to undertake training to better understand food allergies is not a barrier in itself. A study surveying almost 230 FBO staff demonstrated that 80% of servers within restaurants would be interested in participating in future food allergy training (Lee, et al., 2016). This was also found by Donovan et al. (2018) who demonstrated that training sessions offered on food allergies had high attendance rates.

Madsen et al. (2020) suggest that providing context to stakeholders on the need for training, educating them on what it means to live with the risk of allergies, and how the risk could be mitigated more successfully constitute beneficial training.

“[The restaurant staff] didn’t have proper training in order to communicate [allergen advice]. In these situations where mistakes have been made, it’s because people don’t know to flag allergens to me, rather than them not knowing how severe and how bad [my allergic reaction] can be.”

- Consumer, England

“So we do refresh [our training] on an annual basis and you know with the consumer voice to make it more real…Because when you're making a sandwich, you're not necessarily thinking where that sandwich is going. And you’ve got hundreds to make…Our training works well because our, our team members kind of connect to the customer and why that customer needs those controls in place.”

- Food business operator, UK

Further, it was found that surveyed FBO staff expressed a desire for a training programme that is self-paced, incorporates real world examples and uses simple language (Lee, et al., 2016). Finally, an interviewee shared that strong training and communication of staff was evident when the front-of-house staff were familiar with the menu and knowledgeable about allergens. To improve this further, they suggested a daily discussion between the front-of-house/ serving staff and the chef/ kitchen team to discuss the menu and ingredients (particularly when menu changes are frequent) and highlight any allergens present in the dishes.

Staff turnover and time constraints

Problems raised in the evidence. A survey-based study in England found that while most FBOs (29 out of 30) reported carrying out food allergy training, staff knowledge was challenged by factors such as high staff turnover and lack of time committed to offer training opportunities to employees due to competing demands (Soon, 2020).

Clarity of legislation

Problems raised in the evidence. A third challenge that is often faced by FBOs is lack of clarity in the legislation (or its interpretation). For instance, a study surveying business practices related to food allergens in Switzerland found that particularly when providing verbal information, there is a lack of consistency when interpreting key terms such as ‘informed person’ (the designated person to be providing allergen information) (Eisenblätter, et al., 2022). Further, they found that 182 out of almost 400 Swiss businesses provide precautionary information about cross-contact often out of internal concerns about safety. However, other review-based studies indicate that FBOs overuse precautionary labelling and find it difficult to conduct thorough risk assessments. A large cross-sectional survey study representing multiple stakeholder groups (including consumers, healthcare professionals, psychologists, and auditors of businesses) and countries (the Netherlands, Republic of Ireland, Germany and the UK) reported that Precautionary Allergen Labelling (PAL) was inconsistently applied and interpreted (DunnGalvin, et al., 2015). The standards and codes of practice related to PAL are “generic in nature” such that “different food businesses may make opposite decisions about the need for a PAL for the same risk of reaction” (DunnGalvin, et al., 2015, p.9). Risk assessments are also challenging in the absence of clarity on the level of allergen thresholds to constitute an allergen risk (Madsen, et al., 2020). We note here that the use of PAL is voluntary.

‘So I think this is an area of ambiguity across the industry because there is not one way of doing [it], not one way of declaring allergens in either of those areas, I think you've got to provide allergen information to the customer. But how you provide that can vary… it would help to have a consistent approach to how you manage, and risk assess allergens because what we find is that when we're [working with] ingredients, supplies that aren't owned by us, they manage their own processes. They're all very different and tell us about allergens differently.’

- Food business operator, UK

What is suggested in the evidence that may work. The researchers who conducted a study into different perspectives on PAL suggested that the “situation would be simpler” if precautionary allergen information was governed by legislation to allow for a more consistent approach to non-prepacked food regulation and enforcement (DunnGalvin, et al., 2015).

Communicating up-to-date information about menus and ingredients

Problems raised in the evidence. The literature and interviews show that staff knowledge about the allergens contained in the food products is sometimes lacking, both in terms of what food has what allergens (e.g., Young & Thaivalappil, 2018) and also in terms of the allergens contained in the food being served at their establishment (e.g., FSAI, 2017), consumer communication with staff may not be feasible, efficient, or accurate (e.g., Begen et al., 2016; Marra et al., 2017), and recipes and ingredients may continuously evolve making printed menus quickly obsolete (Donovan et al., 2018).

What is suggested in the evidence that may work. A few factors were suggested that may help to improve staff knowledge and communication especially when menus and recipes may change. These included:

- promoting the use of a computerised system such as MenuCal which is used in the Republic of Ireland and Scotland and is freely available and designed to help FBOs meet their statutory responsibilities regarding the management of allergens (FSAI, 2017)

- developing a ‘self-designed electronic allergen management tool’, such as one tool used by a business audited by the FSAI (2017) which “allowed the FBO to enter ingredients, create menus and the allergen information was generated automatically” (p.16). The name or exact working of this tool was unclear based on the available information, but it was suggested to be useful for consumers as they could “tailor the menu according to their allergen requirements online” (ibid.)

- creating, and encouraging the use of, generic allergen templates, allergen information posters and other pre-configured information materials for consumer (Donovan, 2018; Food Safety Authority of Ireland, 2017)

- developing guidance on how to develop allergen-free menus, such as gluten-free menus, to encourage businesses to provide clear, unambiguous information to consumers about foods which are safe to eat (interviews with enforcement authorities, n=5).

Interviews with stakeholders further support this finding from the literature, when describing best practice examples they had experienced.

‘[The FBOs have] got the menu online or on an app, and you can slice and dice it in any way you like, and it comes up with what information you need to make your purchasing decision, whether it is a preference, or a food safety need, or whether you know the nutrition or calories.’

- Enforcement Officer, UK

Collaboration between businesses

Suggestions for how collaboration between businesses could be improved.

An unintended positive consequence identified by one study was that an increase in general allergen awareness in Australia had enabled a ‘greater collaboration and willingness by many organisations to work with and support each other to address the ongoing challenges’ (Koeberl, et al., 2018). This suggests that providing more allergen information to FBOs may create an environment for more joined-up approaches to share learnings and best practice and reduce preventable incidents.

5.5.3 Consumers and patients

Different standards for different allergens

Problems raised in the evidence. There are indications that not all types of food allergens are catered for to the same standard by FBOs. A 2018 mixed-methods study in the UK engaging with more than 250 individuals with food allergies found that those who sought to avoid cow’s milk were less satisfied with the information provided for their specific dietary needs in comparison to participants avoiding nuts, and to a lesser degree those avoiding gluten. Interviews with participants looking to avoid milk found that their experience was that the information on the milk content of foods was often limited and that FBO service staff did not understand their issues- this made them feel like their hypersensitivity was taken less seriously by FBOs. (Barnett, et al., 2018). As this study took place five years ago updated research would be helpful in order to determine whether these different standards are still occurring.

Inconsistency in standards is especially true for geographical areas in which regulations include few mandatory allergens. For example, only eight food allergens are covered in the South African legislation (compared to the 14 under the EU/UK legislation) and those who are allergic to others can find it very difficult to follow an elimination diet (de Kock, et al., 2020). One interview with a consumer based in India shared that even within the country there was variation in their experience of catering to Coeliac disease.

‘[In the] south of India, there are more consumers of rice there rather than wheat. So, basically it became very easy for me to consume food there because at least two of the meals were purely based on rice…The availability of [gluten-free] products was far worse [in the] north of India where wheat happens to be the staple in their diet. So yeah, even while staying in different parts of the countries there has been a huge difference.’

- Consumer, India

Format of information provision

Problems raised in the evidence. Consumers participating in studies we reviewed expressed dissatisfaction in how allergen information was provided, finding that verbal information may be inconsistent, may not always be accurate or be delivered confidently which detracted from the consumer’s perception of trustworthiness of the information (Barnett et al., 2018; Begen et al., 2016; Marra et al., 2017). Again, it would be helpful to have more recent data to determine whether this remains the case.

Suggestions for how the format of information provision could be improved. These studies explored consumer preferences for how their experience could be improved when consuming or purchasing non-prepacked foods. For instance, a study that investigated consumer preferences for allergen information provision using an experimental design found that consumers in Canada preferred the use of symbols to identify allergens present and safety statements that clarified allergens absent from the products being sold (Marra, et al., 2017; see also, Barnett et al., 2018).

‘[I would prefer] clear language and clear signposting on sort of like sleek, slimmed down menus where the information is easy to find would be useful.’

- Consumer, UK

Another study in the EU explored the preferred modes of information delivery and found that most consumers prefer written information in the first instance, as it helps improve the perceived validity of further verbal advice from service staff. In the absence of written information, customers rely on social cues, such as body language, that inform their perception of how trustworthy the verbal information is (Begen, et al., 2016). Based on their findings the authors suggested that the use of written information and standardisation of allergen information provision (e.g. positioning on label next to the food, use of symbols) may be helpful for consumers by ensuring that allergen information is provided in an accessible format. Further research would be needed to test whether these would be effective solutions.

Our findings indicate a preference across stakeholders (consumers, researchers, enforcement officers) to access allergen information in writing and through the use of visual symbols. Reasons noted included the accessibility of information and the accuracy of information. However, it is unclear whether provision of allergen information using this format is effective in terms of consumer confidence and safety and business compliance, and if there are any disbenefits associated with its implementation.

Communication with staff

Problems raised in the evidence. Barnett and colleagues (2018) interviewed 49 consumers who experienced food allergy symptoms after consuming nuts, milk or gluten, as part of a larger mixed-methods study. They found that consumers were sometimes too reluctant to ask staff for allergen information as they felt this might lead to a perceived misunderstanding or possible social embarrassment. Those with milk allergies indicated a lack of feeling understood by FBOs and this presented in a lack of trust in staff as a reliable information source (Barnett et al., 2018). These barriers in communicating with the staff were also echoed in interviews with consumers (n=4)

Suggestions for how communication with staff could be improved. One suggestion to improve consumer experience was to ensure that the service staff are not only trained on food allergens but are also encouraged to proactively ask customers about their allergen needs which may increase consumer confidence and trust in the business (Barnett, et al., 2018). This was also echoed as an indicator of good practice in complying FBOs by an enforcement officer we interviewed.

‘People [FBO staff] who ask people [consumers about their allergies] when they arrive at the table…they clearly communicate this is [a priority], which means hopefully that there has been a completion of [the information loop and] that communication that comes right back [to kitchen staff]’

- Enforcement Officer, UK

Clarity in legislation

Problems raised in the evidence. Regulations in some countries do not specify how allergen information should be shared by food businesses. For example, consumers with food allergies eating out in New Zealand often have to rely on verbal information provided by staff, as written information is not always available (Wham & Sharma, 2014). However, staff might have limited knowledge or lack training on specific food allergens, which then could lead to a false sense of security for consumers with limited or inaccurate information being provided to the consumer.

PAL is another area that both consumers and clinicians find confusing. As demonstrated in a large survey of more than 1,500 individuals with food allergies, the lack of regulation around PAL and use of numerous different statements in many countries has contributed to consumers not understanding what the PAL messages really mean (DunnGalvin, et al., 2019). Consumers often mistakenly think that longer PAL statements indicate reduced allergen risk, whilst this is not necessarily true (Bezuidenhout, et al., 2021). As a result, this has led to loss of trust in PAL, increased risk taking and reduced quality of life for consumers as shown in a multidisciplinary review robustly addressing the perspectives of multiple stakeholder groups (DunnGalvin, et al., 2015). Furthermore, the difficulty in interpreting PAL statements and their risk also makes it hard for health care providers to advise patients avoiding food triggers, which can mean reduced food choices and increased costs (DunnGalvin, et al., 2019; DunnGalvin, et al., 2015). This is in line with findings from an experimental study in Canada showing that consumers placed the least importance on the use of precautionary statements compared with other attributes of allergen information provision (Marra, et al., 2017).

‘Now that everyone [in the food industry] is starting to label everything with [PAL suggesting] trace amounts, I've almost started to ignore the label…because I have eaten a fair amount of both packaged and non-prepacked food that have that label and I have a highly sensitive nut allergy and not once have I reacted.’

- Consumer, Sweden

Suggestions for how legislation could be made clearer. These studies have expressed a need for standardisation of PAL, with several articles suggesting that it should be covered in regulations to better protect vulnerable consumers. In particular, literature highlighted a need to use only one statement for PAL to reduce consumer confusion, keep it short, and use a symbol to indicate allergen presence (Marra, et al., 2017; Bezuidenhout, et al., 2021; de Kock, et al., 2020; Madsen, et al., 202). Furthermore, agreement on allergen testing methods and acceptable levels of allergen presence in food products, as well as implementation of a quantitative risk assessment approach (which ensures that only products likely to cause a reaction have a PAL statement) could help make PAL more meaningful to consumers (DunnGalvin, et al., 2019).

6.1 Strengths of the research

Mixed methods approach: We combined a literature review with qualitative, interview-based research. The interviews were designed to both build upon the strengths found within the literature and address gaps emerging from the reviewed literature.

Systematic process guiding the literature review: Clear protocols were developed with the FSA and our academic and charity advisors to guide the search for relevant literature in two databases (see Appendix A). These were further adapted as appropriate based on the results of early scoping research conducted by our academic advisor (see Appendix B). The revised approach was validated by the FSA before proceeding further with the search, to ensure agreement from each involved party. The two databases used for the search were Web of Science and SCOPUS, which have extensive, international records both from sciences and social sciences. We followed a systematic process for the literature review, guided by PRISMA style of reporting to monitor the number of records included/ excluded at each stage of the screening with clear reasons for exclusion as set out in the search and screening protocol (see methodology for details). Finally, we used the framework developed and recommended by DEFRA to undertake critical assessment of the evidence by rating the quality of the articles in terms of robustness and relevance.

Consistent use of research tools guiding the qualitative fieldwork: A clear set of semi-structured topic guides were produced to guide the interviews with four stakeholder groups: researchers in FHS (n=3), enforcement authorities (n=5), food business operators (n=1) and consumers/patient advocates (n=4). This ensured that different researchers were using the same set of research tools to optimise parity across discussions and mitigate the influence of individual interview styles and approaches.

Extensive geographical coverage: The literature review and our fieldwork cover an extensive range of countries and regions across the world (18 countries or geographical regions), including several records that are not country-specific and thus more widely applicable to the EU or worldwide. It is to be noted that the evidence base does not cover one country that was intended to be within scope, namely Belgium, because there was no legislation or other relevant literature available in English.

Coverage of research questions: The findings from the literature review showed that the search and screening process resulted in a high volume of articles, in particular related to research theme one on legislation and guidance per country, as well as research theme five on stakeholder perspectives on what works, why and for whom. These were also supplemented wherever possible with insights gained from qualitative interviews to strengthen the narrative presented in the report.

Peer-review by FSA and academic advisor: All outputs from this project, from the development of the search protocols, interview topic guides, draft interim and final reports and presentation slides, were peer-reviewed by our academic advisor, Dr Audrey DunnGalvin who is a Lecturer and a Programme Director at University College Cork and also the CEO of Anaphylaxis Ireland.

6.2 Limitations of the research and barriers

Research gaps in literature: There were relatively few results related to research theme three on enforcement process and capabilities or research theme four on non-compliance and consequences. We did try to follow up these gaps through interviews, but it was hard to engage with enforcement officers internationally, so this further limited our findings. Some reasons for this include the relative lack of legislation related to food allergen information provision in the non-prepacked sector, compared with the more widely mandated provision within the prepacked sector. There is also little to non-existent consistent reporting of allergy-related deaths and incidents associated with the non-prepacked sector, limiting our ability to identify trends in the data as a function of legislative changes, business characteristics or other factors.

Availability of literature in English: Further, there was a scarcity of literature published or available in English from certain countries such as Belgium, which was a requirement for inclusion established at the out-set of this project.

Challenges in recruiting stakeholders for interviews: Despite purposive mapping of stakeholders for interviews and wide-reaching sampling and recruitment strategies, we were unable to meet the target of 15 interviews. This is despite a high level of outreach efforts with almost 125 emails sent by RSM along with additional emails sent by our advisor and the FSA team. Two categories were particularly difficult to recruit interview participants for – international enforcement authorities and food businesses within and beyond the UK. The response rates from stakeholders were very low, particularly in contexts where we did not have prior relationships or a history of engagement with the stakeholder.

Tight timescales for the project: An additional barrier came from the fact that the project had tight timescales (as this was primarily a rapid evidence review) which made it challenging for stakeholders who were interested in taking part but unable to respond within the specified timelines.

6.3 Considerations for further research